After decades of change and problem solving, the multibillion-dollar heir to the Hubble telescope is slated to launch this fall

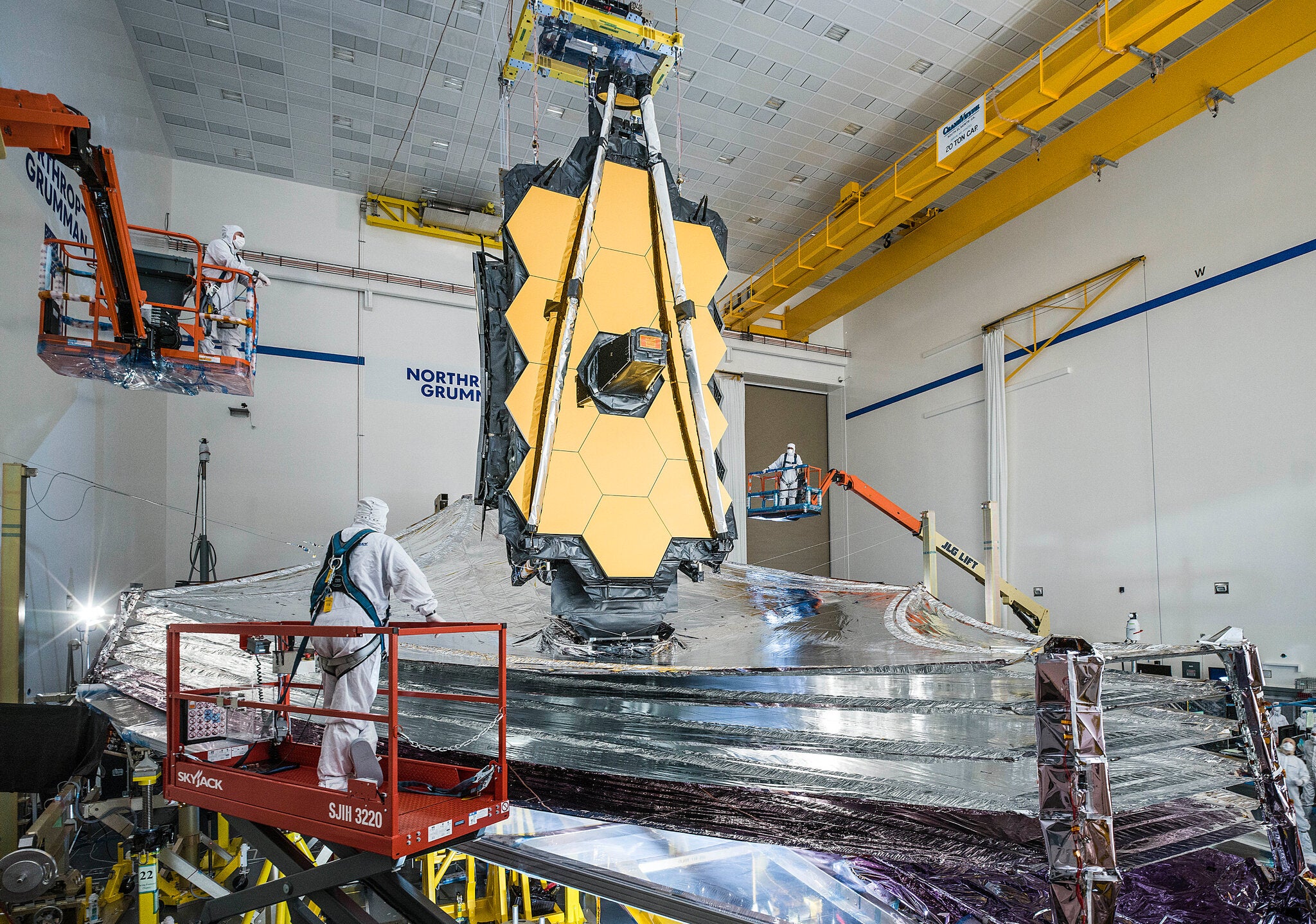

Recent tests of the James Webb Telescope's solar shield at the Northrop Grumman hangars in Redondo Beach, California. December 2020.

It takes a lot of time, money and inspiration to create a new space telescope. Astronomers pestered NASA with a project for the next space telescope after Hubble even before it was launched into orbit in 1990. Then it seemed to them that the project would cost no more than a billion dollars and would be launched in the first decade of the 21st century.

Thirty years later, $ 8.8 billion, multiple setbacks, funding crises, and congressional threats of project cancellation, James Webb Space Telescopefinally ready to run. NASA plans to launch it into orbit as early as October 31 on the European Space Agency's Ariane-5 rocket from the launch site in French Guiana.

During a recent meeting of the American Astronomical Society, technologists and engineers showed the telescope unfolded, hoping this would be the last time the telescope would be deployed on earth.

“The next time this observatory looks like this,” said Eric Smith, a scientist involved in the telescope program, “it will be beyond the orbit of the Moon and will be visible to us as a 17th magnitude point light source.

The telescope, completely assembled in a clean room at the Northrop Grumman hangar in Los Angeles, looks like a giant sunflower on a surfboard on the virtual conference cameras. The flower petals are 18 gold-plated beryllium hexagons that form a plate 6 meters in diameter. The surfboard, on which he will forever glide on the far side of the Moon, serves as a sandwich of five layers of Kapton plastic that will shield the telescope from the heat and light of the Sun.

The telescope, named after NASA's chief executive behind the Apollo program, is nearly three times the much-hyped Hubble and seven times more sensitive at detecting faint stars and galaxies near the edge of time.

Acoustic tests of a part of the telescope spacecraft that simultaneously serves as a solar shield and a busbar

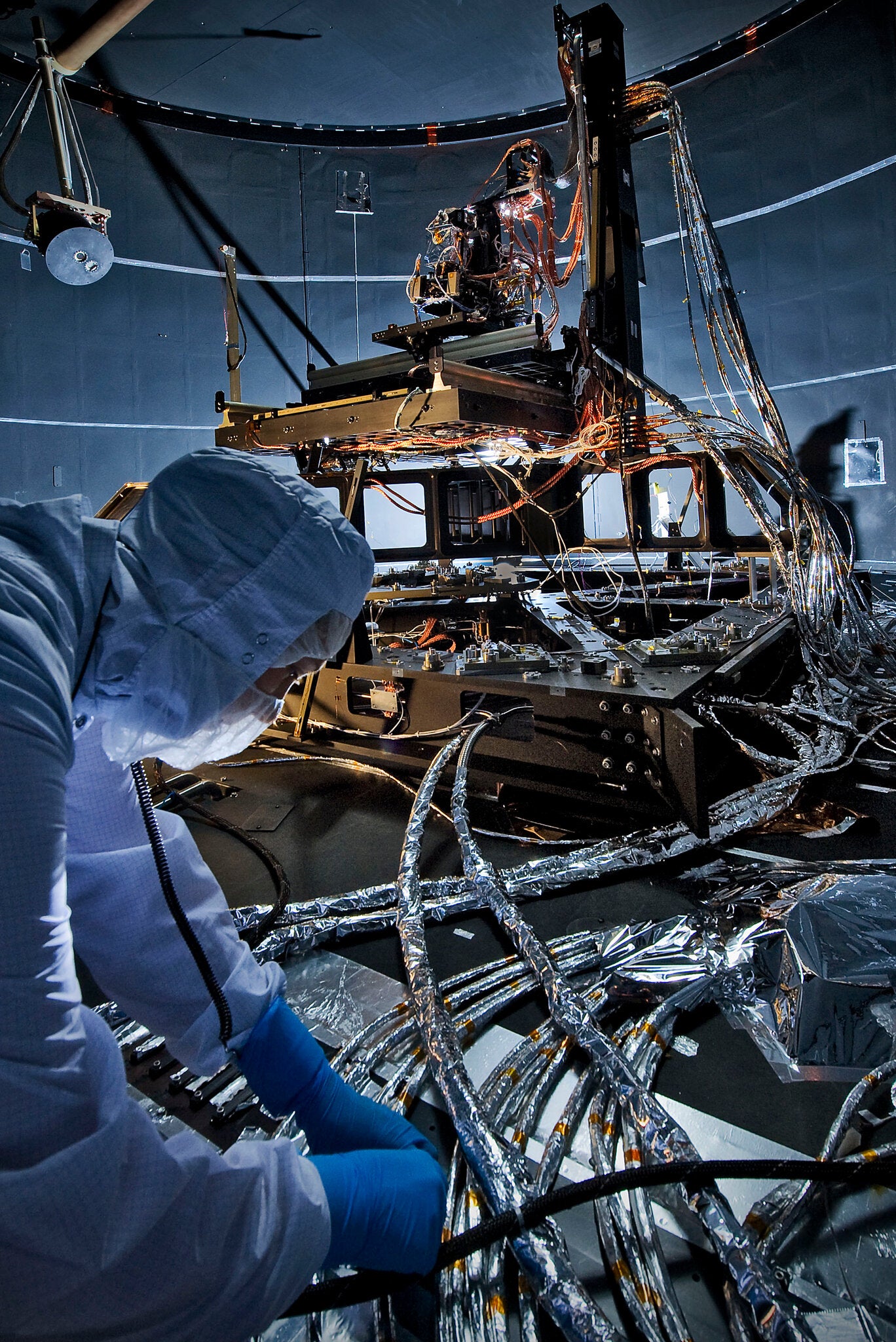

Engineer Erin Wilson added aluminum film to electrical cables to protect against hypothermia during tests of the telescope's optical equipment.

Descending the telescope into the test apparatus. The telescope is so large that it has to be folded down to launch on an Ariane 5 rocket.

To send the shield and telescope mirror into space on the ESA-provided Ariane-5 rocket, they need to be folded - and then they must deploy at a distance of 1.5 million kilometers in open space in the first month after launch, which will require about 180 operations. Over the past few years, engineers have practiced various stages of this deployment procedure over and over again.

On one of the early runs, the sun shield broke, delaying the project again.

So far, engineers believe that they have done everything, but they are terrified of the coming six-month period of deploying and testing the telescope in space. In addition, Smith says there are still a couple of centimeter-sized holes in the kapton that need to be repaired.

The telescope's mission is to explore that part of space history that was inaccessible to Hubble. In the period from 150 million years to a billion years after the beginning of time, the first stars and galaxies were born. They began to burn off the gloomy hydrogen fog that prevailed in space after the Big Bang. How exactly this happened is still unknown.

To complete the mission, the telescope must be tuned to a light different from what our eyes or Hubble see. As the expansion of space quickly blows away the earliest stars and galaxies, their light is redshifted, and its wavelength increases - much like the sound of a siren passing by an ambulance, which becomes lower.

Engineers tested "snow clearing" on a test mirror at Goddard's space flight center. They shower the mirror with a stream of frozen carbon dioxide snow that cleans large mirrors without scratching them

Preparing the telescope for October trials

Five layers of a full-scale engineering model of the telescope's solar shield laid out for strength testing in a Northrop Grumman hangar in 2013

Therefore, the blue light emitted in the distant past by a newly born galaxy full of new bright stars, stretched out and passed into the invisible infrared range - became thermal radiation - by the time it reached us 13 billion years later.

As a result, the Webb Telescope will produce space postcards in colors that no eye can perceive. But in order to recognize this weak thermal radiation, the telescope must be very cold - no higher than 45 ° K - so that its thermal radiation does not drown out radiation from distant space. Therefore, he needs a solar shield that will keep the telescope in a constantly cold state.

Also, infrared radiation is ideal for studying exoplanets - planets orbiting other stars. This approach was promoted by the acclaimed 1996 report “The Hubble Telescope and the Future, Exploration and Search for Origins: Ideas for Ultraviolet-Optical-Infrared Space Astronomy”, written by the Carnegie Observatory Committee under the direction of Alan Dressler.

Their ideas were prophetic. Exactly three exoplanets were known at the time. In the decades that followed, as the Webb telescope went through all the stages of painful development, exoplanet research flourished. The Kepler mission found thousands of exoplanets, which implied that there should be hundreds of millions of exoplanets in our Galaxy that astronomers could study with the Webb telescope.

And one of the most anticipated first results of the work of the James Webb telescope will be data on the planets of the TRAPPIST-1 system., a lonely star located just 40 light years away. Several planets revolve around it, three of which are rocky, and are located in the so-called. " Habitable zone ", due to which liquid water can be on their surface. The James Webb Telescope, among other things, will be able to study the atmospheres of such planets, based on their interaction with the light of their stars. And this is the first step towards examining the question of whether potentially habitable planets are inhabited - or at least to assessing the likelihood of this.

Reduce the number of gray-haired astronomers

Sara Seeger, planetary scientist and professor of physics at MIT

The search for life on exoplanets is the central theme of Nathaniel Kahn's new documentary on the James Webb Telescope, Planet B Hunt. The film will premiere at the South by Southwest Festival in March. To Kahn's surprise, the film also showcases a sociological revolution in astronomy - many of the leaders in exoplanet research are women.

The film highlights researchers such as Jill Tarter of SETI, a pioneer in the search for extraterrestrial civilizations; Natalie Bataglia of the University of California, Santa Cruz, leader of the Kepler mission, who is making the observation plan for the James Webb Telescope today; Margaret Turnbull, an inhabited planets expert at the University of Wisconsin, a former candidate for governor of this state (Kahn interviewed her while she was working on hives in her yard); Amy Lo, an engineer at Northrop, freed from assembling the parts of the James Webb telescope into a coherent whole, tuning racing cars.

“It doesn't matter what I think about it,” Tarter says when Kahn asks her about the existence of life in the universe. No one addressed the theologians and priests: "We are here not engaged in religion, but in science."

Kahn received Academy Award nominations for the films My Architect, dedicated to his father, the architect Louis Kahn, and Two Hands: The Story of Leon Fleischer, about a pianist who has lost control of one arm due to a neurological disease. As a hobby, he has been studying astronomy all his life. He intended to make a film about the creation of a telescope, but as he said in an interview, one of the beauties of filming is that “you start filming about one thing, the James Webb telescope, and it naturally develops into a deeper story. And this story is the emergence of women at the forefront of astronomy. "

Sara Seeger, a planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who helps plot the film, said the appearance makes perfect sense. "When exoplanets were a completely new field of science, it was by definition not dominated by old white men," she told The New York Times. "The old scientists did not want to plunge into a new and seemingly risky field of activity, so there was no one to spread their prejudices to the community."

Margaret Turnbull, still from the movie "The Hunt for Planet B"

Jill Tarter, astronomer from the SETI Institute

Natalie Bataglia from the University of California

Amy Lo, engineer from Northrop

Seeger recalls how surprised she was that at the cosmology conferences, nearly all of the speakers were men with gray or graying hair. “There were no niches in cosmology for new people to enter,” she said. "There was no one older than 40 at the exoplanet conference, and most were under 30."

Battaglia said that men like Michelle Mayor and Didier Kelotz of the Geneva Observatory, who shared the 2019 Nobel Prize for the discovery of the first exoplanet, and William Boruchki of the Ames Research Center, who conceived and led the Kepler mission, first led the way in exoplanet research. But women have successfully developed and advanced this area further.

“If you talk to older women who study exoplanets, you will find that all our stories are different,” Bataglia said. - We survived for different reasons. And they stayed for various reasons. And now that we are here, it may be easier for other girls to imagine themselves on the same path. "

Forward to the past

Launch of the Ariane 5 rocket from the Kourou Cosmodrome in French Guiana with payload from satellites, 2006.

To date, 4332 astronomers from 44 countries have submitted their proposals for the first round of observations with the James Webb Telescope. These numbers were voiced by Christine Chen of the Space Telescope Science Institute during a conference on the James Webb Telescope. 31.5% of researchers are women, which is roughly the same as the current statistic that about a third of doctoral degrees in astronomy were earned by women.

“We have natural diversity,” project manager Smith said during the conference. And he added: “As scientists, we understand that the universe rarely manifests itself through data that supports our models and theories, and more often gives us data that go beyond expectations, and bring us closer to the universal truth. And just as we should strive to understand data that differs from our previously formed ideas, so we should look at different perspectives when planning and developing missions. "

The fall launch of the James Webb Telescope will be one of the greatest events of this year for space science - along with the landing of another robot on Mars.

It would not be so daring to assume that if we continue our research at the same speed, then in the next half century we will be able to find out that life in any form exists in the nearest part of the cosmos. Perhaps it will hide under the ice of a giant satellite of the planet, under a stone of Mars or in some hot swamp of an exoplanet. Any hint of its existence would be a giant step towards understanding our own origins.

As Dressler et al. Wrote in a 1996 report, "A remarkable triumph of 20th century astronomy was the demonstration of the truth of the idea that our origins, and perhaps our destiny, lie somewhere among the stars." Hinting at the popularity of science fiction in films, television shows and books, they wrote that "the great themes of human existence are increasingly being projected into space."

"Perhaps our physical travel into space will not take place for several generations in a row," they concluded, "but our minds are already living in the Space Age."