Unfortunately and somewhat ironically, in 1996 DEC itself fell prey to destructive competition. Smaller, faster-growing companies such as Sun Microsystems and other PC makers have penetrated deeply into the business, making computers even smaller and cheaper. Within a year after the start of this story, DEC will be sold to its competitors and will cease to exist as a public company. Much has been written about this tragic downfall (see link above), but this is not the story I am going to tell here. This is a post about what happens when money becomes your only motivator, and how waiting for money can make you do irrational things.

So 1996. By that time, I had been with the company for 10 years and worked as a hardware systems engineer for the Alpha Workstations group in Maynard, Massachusetts. My job was to design the Alpha NT workstation processor boards and motherboards, which were a weird hybrid thing based on the company's proprietary processor technology, but that could run Microsoft Windows NT, the "business version" of Windows at the time.

In previous years, DEC had developed its own operating systems (VMS) and also created Unix-based workstations, but during this time the company was trying to solidify its place in the segment of the workstation market, which was rapidly moving towards cheaper Intel / Windows-based systems. Our Alpha processor was much faster than anything else at the time, but it didn't run Intel-based software directly. Because of this limitation, most programs had to be emulated, which slowed things down to the point where most of the benefits we offered were lost.

It was a desperate, insoluble situation, and we struggled to survive. Management insisted that new projects be done faster and cheaper than ever before, trying to squeeze what used to take years to months. So they launched a secret incentive program available to a small group of research engineers on key projects to try and achieve these goals.

In this program, $ 2 million has been set aside as a potential bonus fund for members. The maximum theoretical payoff for an engineer was $ 25,000, and this was all kept secret as many, including our production and technical staff working on the project, were not part of it. When I was told that I would be included in this program, I was designing a CPU board for the Alpha XL366 NT workstation. It was supposed to be a low-cost workstation that included the latest Digital Alpha processor running (at the time) at a crazy speed of 366 MHz - more than twice as fast as our competitors.

$ 25,000 was not enough for retirement even in 1996. I knew that earning this money would not make me rich, but it was still a lot of money, and it was much more than any bonuses I have ever had with the company. But it was written in small print in the incentive program that you will earn UP TO $ 25,000. That way, you could earn a certain percentage of the $ 25,000 total for every percentage you cut the system cost, and you also get a certain percentage for every day you cut the system release schedule. So, if you could create your project cheaply enough and fast enough, everyone on the team could earn up to $ 25,000. That is, everyone who was invited.

If you assume that such a setup was a recipe for disaster, you are right. Problems began to form in the program almost immediately. My problem was that I was well versed in my hardware design, and I was already working on a more expensive 8-layer PCB, and already using a fair amount of better quality but expensive components. This limited what I could do to control spending, but I could still try to get things done faster. In contrast to my situation, some of my colleagues were working on a side project that had just started and they could immediately adjust the design to maximize their cost and schedule savings and increase their payouts.

Our product team grumbled about this because it seemed unfair that one team could have a better potential to maximize their bonus than another. But, as I will explain in a nutshell, the real problems arose later, when the hardware was designed and built.

The design phase of this project was the most stressful work environment I have ever found myself in. Within two to three months, we designed and built a complete workstation, the development cycle of which previously took six months, and before that, years. I remember our Signal Integrity team and I screaming to each other about how many capacitors we needed. These tiny devices equalized the power of the system, but they wanted too many to be added to make the design cheap and easy to assemble. In the end I won the argument by taking the previous workstation we created and going to the lab, removing about half of the capacitors from it with a soldering iron while measuring the output power, to prove that Signal Integrity remained good and that our standards had become too conservative.

The Signal Integrity team relented, but they didn't like it. They said the project would fail and we would have erratic system behavior because they thought we were cutting corners. Meanwhile, I usually woke up at 4 in the morning in complete stress and insomnia. Sometimes I would just refuse sleep and go to work at such an early hour, and sometimes, while there, I would meet other exhausted engineers who could not sleep either. I cut as much time as I could and also cut costs a bit. A $ 25K bonus was out of the question at the time, but there was still hope of $ 10K or more.

Finally the day came when our new equipment rolled off the assembly line and was ready for testing. A junior engineer named Mike, who was assigned to work with me, and I came to our facility in Salem, New Hampshire, where they had just made an Alpha XL366 processor number 0001. We met with the chief process engineer of our projects while he was filming our processor from the assembly line. He plugged it into a test board and plugged in a keyboard and monitor. A copy of Windows NT was loaded into the system and it came to life. A huge wave of relief washed over me when he booted up the OS and opened the solitaire app.

Everything worked fine. Luck was with us that day, because the Chief Engineer played the game to the end, and as usual, when you win in Windows Solitaire, the cards jumped to the victory screen. On this machine, the speed was so fast that the animation looked blurry, which is a really good sign that our processor is a performance leader.

Making a structure that works the first time is not an easy task, and I returned from that trip in a very good mood and the bonus situation looked great. But the luck was short-lived. A week later, we got ten cars to our lab in Maynard for testing, and then things went downhill. The machines started to fail. At a random time, for no apparent reason. Not one or two, which could be explained by a manufacturing defect, but all the machines.

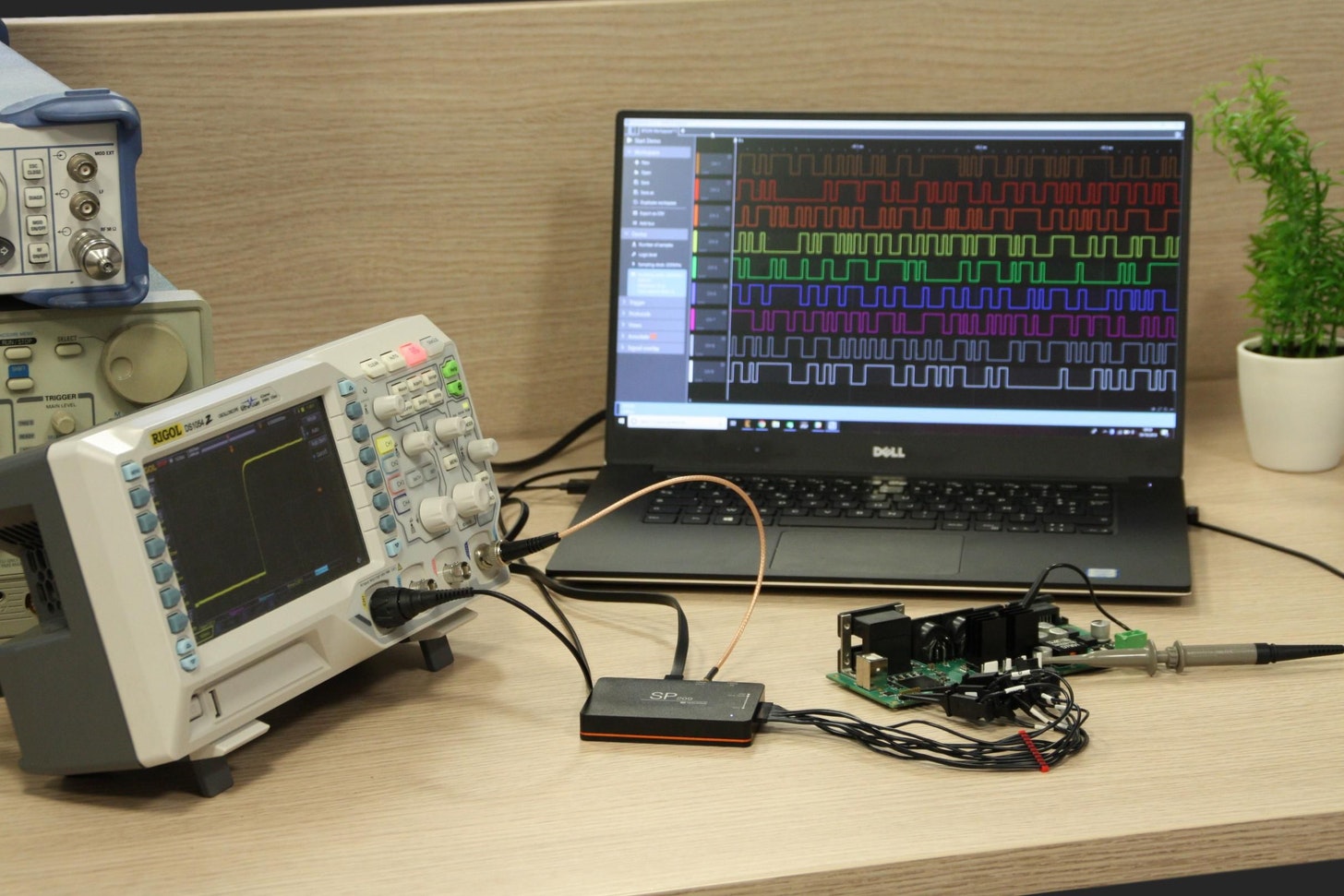

Oscilloscopes, logic analyzers, component specifications and schematics were introduced. Mike and I spent days trying to sort out a phantom problem in the lab, without much help from our Signal Integrity team. As for them, it was because we didn't listen to them and add all the capacitors they wanted and they expressed their opinions very loudly. The problem was that we did not find any fluctuations in power that could indicate design defects of this kind. But we also couldn't find a better explanation for why these machines were failing.

The days turned into weeks, and we watched our theoretical bonus amount get smaller and smaller. There was a rumor in the hallway about how we had lost our project, and I was almost certain that I would be removed from my position as project manager if the project had to be relaunched. If not worse.

One gloomy day, while Mike and I were sitting in the lab, he asked me to give him the specifications of the components of the memory chip that we used for the CPU card cache. He was going to recheck (or recheck for the fourth time for now) our pinout and wiring. Reading the spec, he suddenly jumped up from his seat and thrust the book into me. "THESE ARE FIVE VOLT CHIPS!" he shouted. He gestured excitedly at the board. "MANUFACTURING THE INSTALLED FIVE VOLT RAMS!" I grabbed the book and looked, and it was true. The problem with the five volts on our board was that these chips were fed three volts, not five. Our design was designed to power a variant of the IC that could run on three volts, but the board obviously had the wrong ICs installed.

Another interesting feature of this situation was that if you tried to power something that requires five volts with just three, it would work. Like. But it will be unstable and weird things will end up happening under load. This is exactly what happened. So we checked the parts list of what we sent to production and we got the 3 volt components correct, but somehow they picked the wrong 5 volt component when assembled.

I rushed to my boss to bring the news to him and he felt as relieved as I did because he was also serious about delays. The next time we gave the Signal Integrity group the good news (or maybe bad news for them), I can say that I have never felt so confident about something as I did that day. Manufacturing was in third place and we had to send them rework boards with new chips.

Then we waited. Because the production, as already mentioned, was not included in the secret bonus program, the people who worked there were not even aware of its existence and had no special incentives to speed up the rework. In their opinion, the project was slightly ahead of schedule, so why rush the work and make another mistake? More time passed. They made another mistake anyway and installed the wrong RAM the second time, which I remember getting very angry about.

In the end, they got it all figured out, but that meant our project was about a week ahead of the original schedule and maybe 5% lower in cost. Management held a little secret meeting to award bonuses and we discovered that each of us would receive a $ 2,000 bonus. In the meantime, our sister project managed to minimize the cost and exceed the planned schedule of its project, so that each member of this team received a full $ 25,000.

We were all furious. In a rage over the sweat, tears, and most likely blood shed for this project in recent months, only to be taken away from us what has turned from a bonus to eligibility. Furious at the unfairness of all of this, because others are making so much more money, even though we have worked equally hard. I declined to attend the celebratory event that followed, and even spoke on the phone with a recruiting technician, wondering what our competitors would offer me if I went to work for them.

Then I backed off for a moment. What's going on here? I tried to imagine how the interview with a hypothetical new employer would go:

"IH: So Mr. Utzig, why are you leaving your current company?"

"Me: They gave me a bonus."

"IH: Did you leave because they gave you a bonus?"

“Me: Yes, too little bonus. It was only $ 2,000. "

“IH: Only $ 2,000? What did you expect? "

"Me: $ 25,000."

“THEM: $ 25,000? Seems like a lot. Is this what you expect to receive from us as a bonus if we ever give it to you? "

"I: mmm ..."

I worked at DEC for ten years, and although they paid well there, that was not the reason why I liked the company. I loved my job. Money never mattered to me. I was surprised that it took me such an ordeal to realize this. So in the end I got through it and life went on.

A tall, fair-haired Irishman (also called Mike), who was a mischievous man, conspired with me to get revenge on the signal integrity group. At the next meeting for the recognition of the project, we established a special award, which we called the "Faraday Prize". (Farads are a unit of measure for capacitance named after Michael Faraday.) The award was to commemorate the largest number of capacitors added to the board, and it had a giant beer can-sized capacitor from a 1950s TV mounted on top of an old trophy bowling. We tried to convey this to the head of the Signal Integrity group, but he found out about it and did not show up. We guessed that he doesn't have that much sense of humor.

Was it cruel? Maybe. I'm not sure if the current one would do it, but I did it in 1996. It brought a sense of completeness. I worked for the company for another year until it was bought out by Compaq Computer and Intel. Then I finally gave up my first job and career as an equipment designer for good.

This is where the story should have ended, but there is one little epilogue that really puts everything in perspective for me. It turns out that the management had some concerns about creating an incentive program, which not all project participants knew about. It was unrealistic to include all people in the bonus program, but it was also unrealistic to do without it.

So they set aside a small portion of the fund, about $ 20,000, to be allocated to the "support staff" of the project. These people were lab technicians, manufacturers, PCB layout designers, and others who worked with us on a project in a supporting role. The managers told the R&D staff to designate people who would receive this much smaller bonus, and to choose an amount for each. The figures here were in the range of $ 200-500 per person. Again, these people were unaware of the larger bonus program, nor did they know that they were going to receive a smaller bonus from the pool.

Therefore, when we distributed this money, it came as a complete surprise to them. They didn’t expect more from the project, they were paid for their time, and the project was successful on all counts, in terms of goals and schedule. And when they got that little scholarship, they were thrilled. They didn't expect this, and it was as pure a definition of a bonus as it could be, not right, but just a pleasant surprise.

A few days after that, I received an email from a layout specialist who was doing the job of laying the printed circuits on my CPU card design. She thanked me for taking part in the project and for the bonus money, and said that it was one of her best projects at DEC. I felt guilty and even ashamed for my behavior after that.

I have received all kinds of bonuses and rewards from time to time over the years since, as some expected, some did not. This is common in the tech industry. But I've learned to never take bonuses for granted, even if it's seemingly commonplace. Never complain or worry about any amount received in such a way that I always feel lucky, I am able to get it in the first place.

We are fortunate enough to have a regular bonus program even now at work, it has been in place for many years. Every time it is handed out, my boss will say something like, "So, this time we had a good bonus, but don't count on it in the future."

And I say, “Yeah. I know."