This story took place in the second half of the century before last and, in my opinion, perfectly reflects the spirit of America of that era: a craving for everything new, a combination with adventurism, enterprise and a huge faith in technological progress.

However, to begin with, let's take a look at the Old World, in London, where in 1853 the first pneumatic mail line was built, connecting the London Stock Exchange and the General Telegraph building. The customers of the innovation were, of course, traders, for whom the time of receiving and transmitting information played a significant role in making money. A steam compressor forced air into the pipe, thus accelerating the cylinders with telegrams along it.

The innovation was quickly appreciated and new areas of application were sought for it.

I don’t know who first came to the idea “if a capsule with letters can be sent through a pipe, then why cannot you do the same with people”. But in 1867, at the American Institute Fair in New York, inventor Alfred Beach demonstrated the "elevated train"- train with pneumatic drive inside the tube. He also came up with a design for a short cylindrical shield tunneling machine, about three meters in diameter, made of iron and wood, capable of digging a circular tunnel underground and powered by hydraulic force.

But even at that time it was impossible to simply take and start introducing a new type of public transport into the life of a large city. Previously, it was necessary to secure the consent of the city authorities. And with that, Beach had a problem.

Pneumatic Post Office in Philadelphia

New York policy at the time was governed by William Tweed, who is known as one of the most unprincipled politicians in the history of the United States (it was not easy to obtain this status, the competition in this nomination was fierce). It is also called a symbol of corruption and embezzlement. For example, the construction of the New York County court, which he pushed through and oversaw, cost taxpayers $ 12 million thanks to inflated prices and budget fraud. By comparison, at about the same time America acquired Alaska for seven million (and this was considered a considerable price). All in all, Tweed's gang has stolen more than a hundred million dollars over a decade and a half of his leadership of the organization of the New York State Democratic Party (which actually ruled the city).

One of his sources of income was kickbacks from companies involved in urban public transport routes (horse and steam buses). They saw in Beech a competitor, especially with a patent for their technology, and easily convinced corrupt politicians that the city did not need any other transport.

But since Beach was an inventive person, this did not stop him, and he found a way to get around the obstacles. First, he received permission to lay several pneumatic lines underground. Then he made changes to the project, according to which, instead of several thin pipes, it was necessary to lay one large one, which, allegedly, would unite these lines inside.

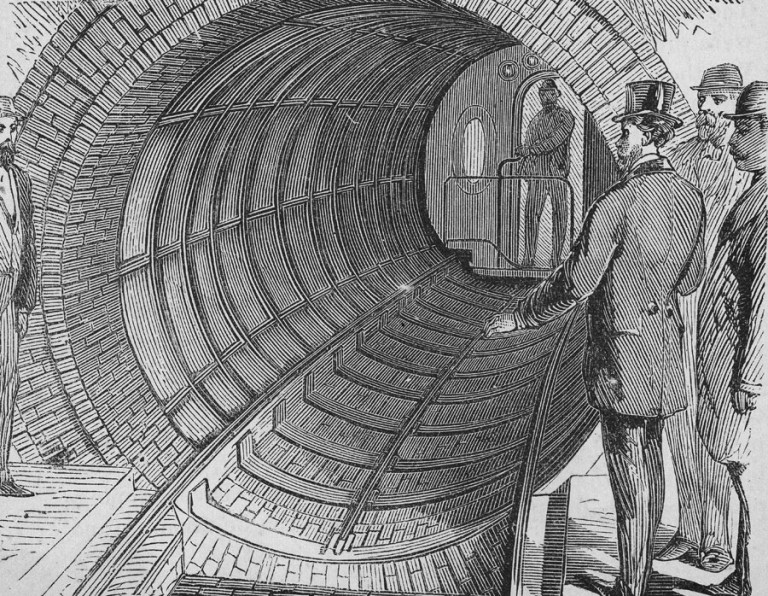

With the necessary papers and a tunneling machine built, Beach set about laying a line under Broadway at a depth of seven meters. Two months later, in February 1870, he presented to the public the finished test part of the "Pneumatic Transit of the Beach" he had conceived. Guests of honor, including City Council officials, and reporters descended into the basement of a Broadway store ... and ended up at an underground train station.

Beach understood the meaning of the first impression and therefore an unusual sight awaited visitors. Instead of a dark and damp basement, usual for buildings of that time, there was a lighted room with a fountain from which a tunnel faced with white bricks emerged. As a New York Times reporter wrote: “ Everyone left surprised and satisfied ... The reliability of the mechanisms and the safety of the working device silenced those who came only to reveal some scientific or technical flaw in this project . "

And already on March 1, the station opened its doors for everyone to ride on the Beach's underground pneumatic train. It worked like this: a huge, one hundred horsepower fan, installed at the rear of the station, pushed the closed train car along the rails at a distance of 90 meters, including the turn, to the next and only station. The engineers then turned the fan over to create negative pressure in the tunnel, which returned the train to its starting point. The train cabin accommodated eighteen passengers. The ride cost a quarter of a dollar (more than 10 bucks at modern prices), but since the train was perceived by the townspeople as a curious attraction, there were enough people who wanted to buy a ticket.

It went well Potential investors began to enter Beach, and he had already planned a whole network of underground tunnels under Manhattan . If it succeeded, New Yorkers would have acquired their own subway not much later than Londoners. And another question, which would be cooler: in London, until 1890, trains ran on steam locomotives and, due to poor ventilation on the landing platforms, it was impossible to breathe. And it is clear that there were no fountains in the English subway.

But Bill Tweed intervened in the matter, who was pretty angered by the deception on the part of Beach. He blocked construction and ordered funding from the state treasury for the construction of an elevated railroad in western Manhattan (from where he planned to begin construction of his Beach network).

Fighting a powerful politician was clearly beyond the power of the inventor. Investors disappeared "like smoke from white apple trees." In fact, Beach was left with only a 90-meter underground pipe, which bored the townspeople very quickly (it would be strange to build a successful business on a demo model). And in 1873 his campaign went bankrupt. Soon a fire broke out at the closed station. Although, when, in the early twentieth century, workers accidentally opened the walled tunnel built by Beecham, it was reported to be in excellent condition.

Scourge learned a lesson from history and no longer went into business, focusing on the work of the editor of Scientific American. The official opening of the subway in New York took place only on October 27, 1904.