In retrospect, my article on the appointment of a new CEO for Intel in 2013 was overly optimistic. One name that stands for: "Opportunity for Intel" . In reality, it turned out not so - over the years, Intel did not succeed, it did not take advantage of any opportunities.

How do we know what didn't work out? Firstly, eight years later, Intel again appoints a new director (Pat Gelsinger), but not instead of the one I wrote about (Brian Krzhanich), but instead of his successor (Bob Swan). Obviously, the company didn't really hit that window of opportunity. And now the question of the company's survival arises. And even the question of the national security of the United States of America.

Problem # 1: mobile devices

The second reason the 2013 headline was overly optimistic is because Intel was in serious trouble by then. Contrary to its claims , the company focused too much on CPU speed and was too dismissive of power consumption , so it could not make a processor for the iPhone, and, despite years of trying, could not make it to Android.

The damage to the company was deeper than just lost profits; over the past two decades, the cost of manufacturing smaller and more efficient processors has skyrocketed to billions of dollars. This means that companies investing in new node sizes must generate commensurately large returns to recoup their investment. The billions of smartphones sold over the past decade have become an excellent source of revenue growth for the industry. However, Intel hasn't made a drop of these revenues, and PC sales have been declining for years.

When it comes to investing in billions of dollars in next-generation factories, you are either doing well in the market or bankrupt. Intel was able to save billions in revenue thanks to a revolution in another industry: cloud computing.

Problem # 2: server success

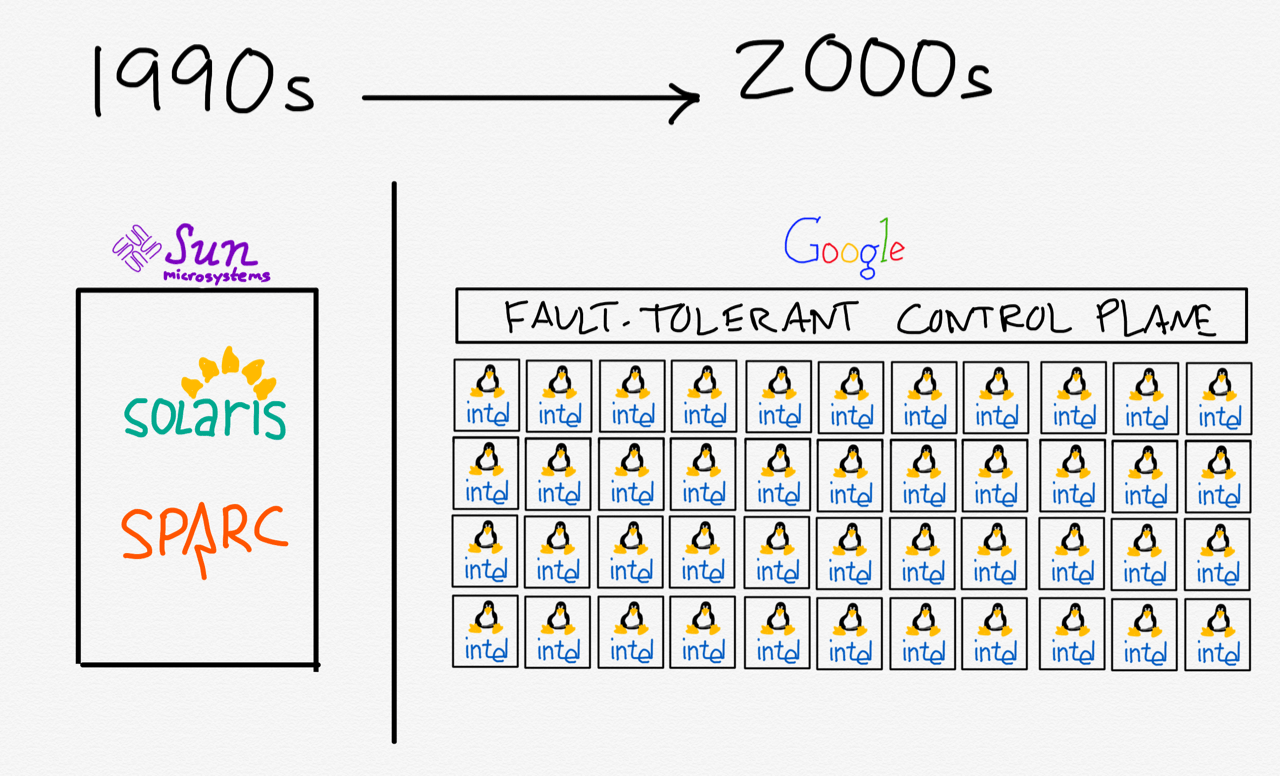

Intel took over this market not long ago. It was initially dominated by integrated companies like Sun with matching prices, but with the explosion in personal computer sales, Intel was rapidly improving performance and dropping CPU prices, especially in relation to performance. Granted, PCs weren't quite as reliable as integrated servers, but at the turn of the century, Google realized that the scale and complexity of the services made it impossible to build a truly reliable stack. The solution was fault-tolerant servers with hot swapping of failed components. This made it possible to build data centers on relatively cheap x86 processors.

Over the next two decades, all major data centers adopted Google's approach, making x86 the default architecture for servers. Intel got the main benefit from this as it made the best x86 processors, especially for server applications. This is due to both Intel's own design and its gorgeous factories. AMD has sometimes threatened the incumbent, but only in low-end laptops, not in data centers.

Thus, Intel avoided the fate of Microsoft in the post-desktop era: Microsoft flew past not only mobile devices, but also past servers that run Linux, not Windows. Of course, the company supports Windows as best it can .both on computers (through Office) and on servers (through Azure). The opposite is true, however: what has recently fueled the company's growth is becoming the end of Windows as Office moves to the cloud for all devices and Azure moves to Linux. In both cases, Microsoft had to admit that their power was no longer in control of the API, but in serving existing customers on a new scale.

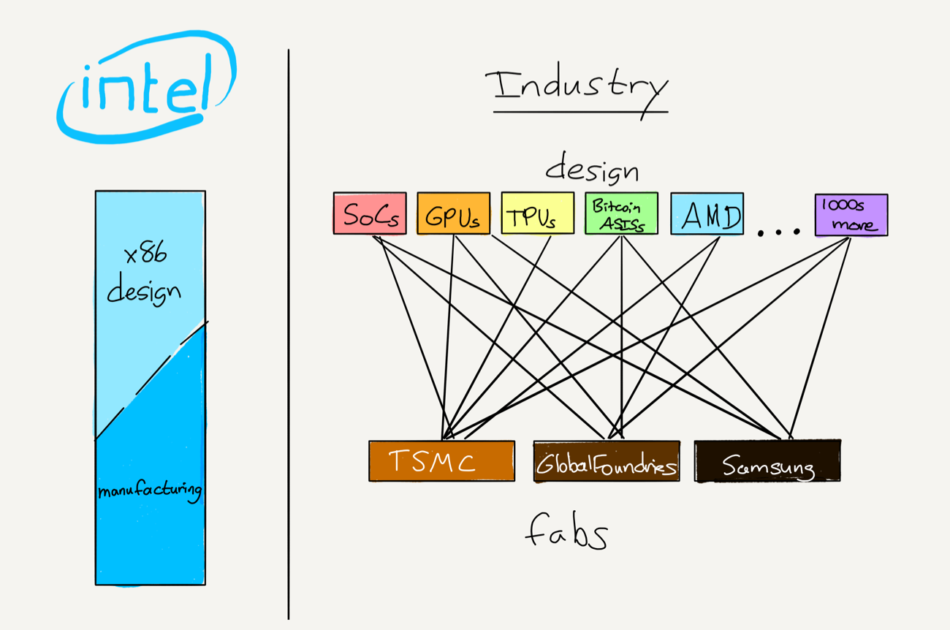

In the mentioned article about the future of Intela similar strategic turn was mentioned. Intel has long relied on the integration of design and manufacturing. In the mobile era, x86 follows Windows forever into the niche desktop market. But it was still possible to keep the business by taking orders for production from third-party customers.

. — . AMD, Nvidia, Qualcomm, MediaTek, Apple — . , : , , , AMD, Qualcomm .

. ARM. , Apple . , . , Intel .

, , , . : Samsung, GlobalFoundries, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) Intel. , , .

, , . , . Intel. , . , Intel .

By the way, my recommendation doesn't mean dropping x86, I added in a footnote:

Of course, they will continue to design x86, but this will not be their only business, and eventually even not the main one.

In fact, the x86 business was too lucrative to take such a radical step. This is exactly the problem that leads to destruction . Yes, Intel escaped the fate of Microsoft, but at the same time did not experience the strongest financial pain that is necessary as an incentive for such a radical business transformation (for example, only after the crash of the memory market in 1984, Andy Grove at Intel decided to focus entirely on the production of processors).

Problem # 3: production

While Intel has been slow to make decisions, over the past decade, the modular-oriented TSMC has received huge orders for mobile chips and installed the world's best chip manufacturing equipment from ASML. In the modular ecosystem, all companies benefit from the growing mobile market - and as a result of this boom, TSMC's manufacturing capacity surpassed Intel.

This threatens Intel on several fronts:

- Intel has finally lost the Mac market, including due to the outstanding performance of the new M1 chip . But it is important to note the reasons for this performance are not only Apple design, but also TSMC's 5nm process technology.

- AMD , Intel, . , AMD , 7- TSMC.

- . , Amazon Graviton ARM, . Graviton — , — , — TSMC 7- ( - 10- Intel).

In short, Intel is losing market share, threatened by AMD on x86 servers and cloud companies like Amazon with their own processors. And I didn't even mention other specialized solutions like GPU-powered machine learning apps that Nvidia develops and Samsung manufactures.

What makes this situation so dangerous for Intel is the issue of scale that I mentioned above. The company has already flown past the mobile market, and while server processors have provided the growth it needs to invest in manufacturing over the past decade, Intel cannot afford to lose cash flow just when it needs to make the most investment in its history.

Problem # 4: TSMC

Unfortunately, this is not the worst. The day following the appointment of a new Intel CEO , TSMC announced impressive financial results and, more importantly, 2021 capital investment forecasts from Bloomberg :

TSMC sparked a global rally in semiconductor stocks when it announced a whopping $ 28 billion in capital investment this year - a staggering amount to expand its technology leadership and build a plant in Arizona to serve key US customers.

This is a huge investment that will only solidify TSMC's leadership.

, - . TSMC 25 28 2021 17,2 . 80% CPU, TSMC . , Intel , TSMC.

The way it is. Probably at the moment Intel has ceded leadership in the production of microcircuits. The company maintains high margins in CPU design and can eliminate AMD's threat by outsourcing its cutting-edge chips to TSMC. But this will only increase TSMC's leadership and will in no way help solve Intel's other problems.

Problem # 4: geopolitics

Intel's vulnerabilities aren't the only thing to worry about. Last year I wrote about chips and geopolitics :

, , . , . , .

, , :

, . , Samsung, . — . Intel , - , Intel .

, . , , . , . , TSMC.

, . , , , . TSMC Samsung .

Just a few days ago, TSMC officially announced the construction of a 5nm plant in Arizona . Yes, today these are advanced technologies, but the plant will only open in 2024. Nonetheless, it will almost certainly be the most advanced factory in the United States to handle outsourced orders. Hopefully Intel will surpass its capabilities by the time it opens.

Note, however, that the interests of Intel and the United States do not coincide. The former takes care of the x86 platform, and the US needs advanced general purpose factories on its territory. In other words, Intel always prioritizes design, while the United States prioritizes manufacturing.

Incidentally, this is why today Intel is less willing to fill third-party orders. Yes, a company can do this out of the need to load production capacity for a return on investment. But he will always put his own projects at the forefront.

Solution # 1: section

That's why Intel needs to be split in two. Yes, the integration of design and manufacturing has been the backbone of the business for decades, but now that integration has become a straitjacket that holds back the development of both. Intel's development is constrained by manufacturing difficulties, and manufacturing itself suffers from inappropriate priorities.

The main thing to understand about microelectronics is that design margins are much higher. For example, Nvidia has a gross margin of 60-65%, while TSMC, which makes chips for it, is closer to 50%. As I noted above, Intel's margins are traditionally closer to Nvidia's due to the integration of design and manufacturing, so its own chips will always be a priority for its manufacturing division. This will suffer lead service and flexibility in completing third-party orders, as well as the effectiveness of attracting the best suppliers (which will further reduce margins). There's also a question of trust: Are competitors willing to share their designs, especially if Intel prioritizes its own design?

The only way to address this priority issue is to spin off Intel's manufacturing business into a separate company. Yes, it will take time to build customer service departments, not to mention the huge library of open intellectual property building blocks that make TSMC a lot easier to work with. But the autonomous manufacturing business will receive the main and most powerful incentive for this transformation - the desire to survive.

Solution # 2: subsidies

Spinning the manufacturing business out into a separate company also opens the door for government money to be pumped into this sector. It makes no sense for the US to subsidize Intel right now . The company is not really building what the US needs, and the company clearly has culture and governance issues that cannot be solved simply by cash injections.

This is why the federal subsidy program must act as a purchase guarantee. The state buys a certain number of 5nm processors produced in the USA at such and such a price; a certain number of 3nm processors produced in the USA at a certain price; a certain number of 2nm processors and so on. This will not only set production targets for Intel, but it will also nudge other companies into the market. Perhaps global manufacturing companies will return to the game, or TSMC will build more factories in the US, or perhaps in our world of almost free capital, a startup will finally emerge ready to revolutionize.

We are undoubtedly oversimplifying the problem. There are many factors in electronics manufacturing. For example, packaging of integrated circuits (assembling a chip into a package) moved abroad a long time ago in pursuit of lower costs and is now fully automated. It's easier to get it back. However, it is imperative to understand that it will take many years to restore competitiveness, let alone US leadership. The federal government has a role to play, but Intel has to accept the reality that its integrated model no longer works.