Last month, China spurred other players to actively explore the moon with its mission to deliver lunar rock samples. At least eight spacecraft from countries such as Russia, India, China, Japan and the United States are expected to land on the lunar surface in the next three years.

For the first time ever, exploring the moon will explore some of the scientifically most intriguing but sensitive regions of the moon - those at the poles. Scientists are interested in water that is frozen in shaded craters. But they are also concerned that the increase in cargo and passenger traffic to the moon could lead to contamination of the ice itself.

Ice is important to scientists for a variety of reasons. Some want to analyze pristine samples to find out how and when the Earth and the Moon accumulated water billions of years ago. Others want to mine ice to fuel rockets at future lunar bases.

Researchers face tough choices. Should you start digging right away to work out the processes by which you can extract ice and turn it into fuel? Or act slowly to preserve scientific data encoded in ice? “Right now, we have scientists who say we can't even get close to it because we'll destroy it,” says Clive Neal, a geologist at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. "Others say we need it, so we'll just do it."

These contradictions need to be resolved soon, especially as NASA plans to send a series of missions to the South Pole, starting with robotic landing devices in 2022 and ending with sending people to the moon for the first time since 1972.

A report from the influential US National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) argues that space agencies must prioritize what they want from the lunar poles in order to effectively explore them. The International Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) is also assessing the situation and will decide in the coming months whether to issue new guidance for spacecraft going to the moon. NASA is awaiting COSPAR's decision and will likely update its own rules for visiting the moon.

As the exploration of the moon accelerates, "we must not harm future scientific research," says Lisa Pratt, NASA's planetary protection officer. The question is, "how to do it right?"

Not a single spacecraft has ever visited the poles of the moon. The only mission that attempted to get there was the Indian Vikram lander, which crashed about 600 kilometers from the South Pole in 2019. China plans to launch the Chang'e-6 mission, which will travel to the Moon's South Pole, collect soil with ice and deliver them to Earth in 2023. This device is the successor to Chang'e-5, which successfully collected rock samples in the mid-latitudes of the moon last December. Japan and India are also contemplating launching robots to the South Pole, as are Russia and Europe.

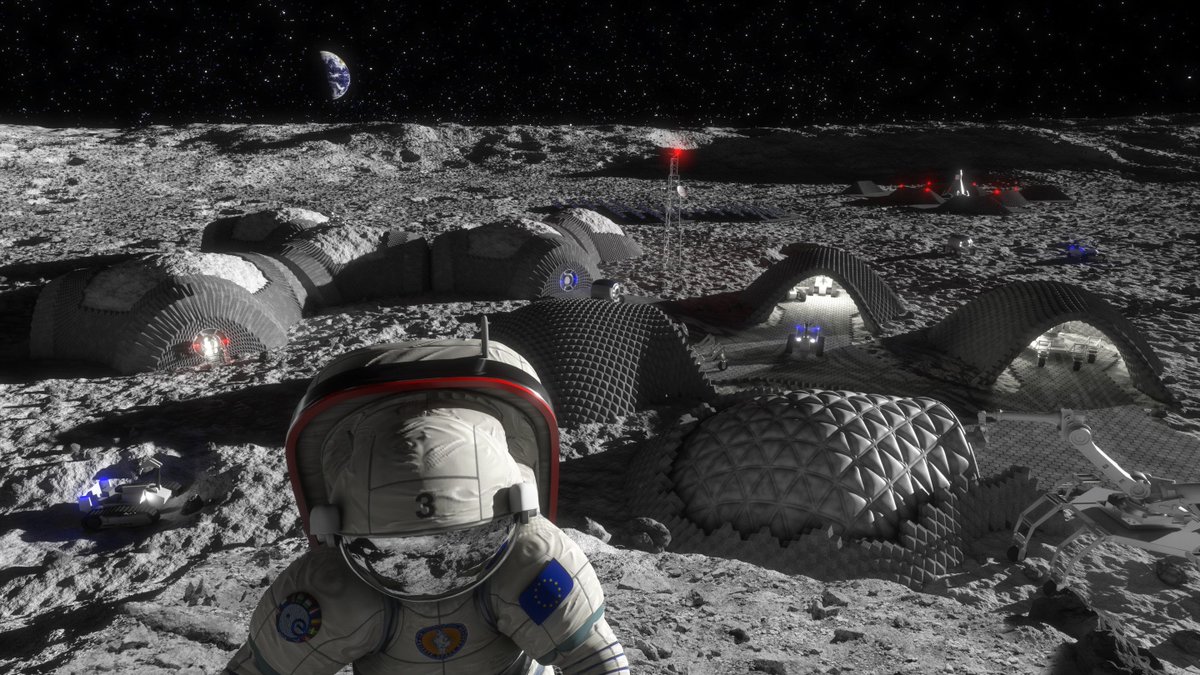

And then there's NASA. Under President Donald Trump, the agency was preparing a series of pole-oriented missions to the moon. According to current plans, NASA will send two automated lander to the South Pole in 2022 and a robotic rover called VIPER in 2023. He will have to drill the lunar soil to a depth of one meter. Then a year later, it is planned to send people who will begin to explore the craters of ice. One of the tasks is to collect the ice and send it to a lab on Earth for study, according to a NASA report released last month.

The possibility of lunar ice contamination is a problem that no one thought about five decades ago, when the Apollo astronauts became the first people to set foot on the lunar surface. At that time, scientists believed that the moon was completely dry. Only in the last decade or so has it become known that water is present in many places, including in shaded polar craters. Scientists have even found mineral water in at least one sunlit spot on the moon.

All this water could have reached the moon thanks to asteroids, comets, or the solar wind bombarding its surface. Part of it could have remained after volcanic eruptions that brought it to the surface from deep within. Whatever the source of lunar water, it contains important scientific information.

Ice in craters at the poles of the moon, devoid of sunlight, has been accumulating for billions of years. If so, then it contains a record of not only the early history of the Moon, but also the history of the Earth. The moon probably formed when a giant object crashed into the newborn Earth about 4.5 billion years ago, tearing off huge chunks that fused with the moon and closely linked their stories. On Earth, geological activity, including plate tectonics, has erased much of the planet's early history. But the Moon does not have such activity, so it is an excellent subject for study.

“The history of lunar water will provide many clues to how the solar system developed,” says Ariel Deutsch, a planetary scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California.

Realizing the importance of lunar ice, many researchers are wary of studying it. In particular, some of them are considering the possibility of ice contamination by rocket exhaust gases.

Parvati Prem, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory in Lorel, Maryland, and her colleagues recently simulated the landing of a medium-sized module near latitude 70 ° - a few hundred kilometers from the South Pole ice craters. Simulations have shown that even if the rocket descends at minimal jet thrust, water will be sprayed from the engines, which will eventually spread throughout the entire moon. Even after 2 lunar days - 2 Earth months - about 30–40% of the imported water will remain on the lunar surface. “The main takeaway is that water vapor is indeed spreading everywhere,” Prem says. Thus, the moon's polar ice has already been contaminated by past exploration missions.

The international group COSPAR surveyed hundreds of planetary scientists how worried they are that lunar exploration could interfere with science at the poles. More than 70% of respondents to the 2020 survey said they are concerned that pollution could jeopardize scientific data stored in the ice of the moon, says Gerhard Kminek, planetary protection officer for the European Space Agency in Noordwijk, the Netherlands.

In an official document presented by NASA, 19 scientists, including Prem and Deutsch, propose sending a mission called "Origins-first" to a shaded crater at one of the Moon's poles. The goal is to collect enough pristine ice samples before exploration of the moon begins. The mission will show how valuable scientific evidence about ice is and whether mining should be delayed, says Esther Beltran, a scientist at the University of Central Florida in Orlando and co-author of the paper.

NASA currently has no funds allocated for the Origins-first mission. It continues to plan to send several spacecraft to the moon's polar regions. But the agency is listening to scientists who are anxious to get it right and intend to proceed with caution, says Pratt, a planetary protection agency officer. “We need to balance the drive to use resources with the need for scientific discovery and knowledge,” she says.

Meanwhile, if COSPAR adopts the new principles of lunar exploration, it is likely that NASA and space agencies of other countries will. COSPAR's current leadership requires countries to compile a list of all organic materials such as carbon composites, paints and adhesives that will be on board the lunar craft. Having such a list would help reduce concerns about future pollution, Kminek said. Scientists will know what kind of anthropogenic material will enter the lunar environment. Perhaps it will be proposed to compile a list of gases that can be emitted by vehicles or life support systems. “Relevant players, including the Chinese space agency and commercial companies such as SpaceX and Blue Origin, sat at the table with COSPAR to discuss these possible changes,” says Kminek.

However, despite the ongoing debate, some scientists are not overly concerned about pollution. Neal and others note that water vapor from rocket exhaust gases only settles in a thin layer on the lunar surface. It doesn't take much work to get to the desired ice. The NASEM report also notes that there is little risk of ice contamination. And Kevin Cannon, a planetary scientist at the Colorado School of Mines in Golden, believes that a little pollution is fully justified by knowing where and how the ice is distributed. He made a map of the places where the largest and most accessible deposits may be.

Several more ideas have been proposed for protecting lunar ice. One proposal is to keep one of the poles of the moon for science and open the other for mining. It is also proposed to designate exclusion zones for some ice craters. There are many such craters, from tiny pits smaller than a human hand to large ones 10 kilometers across, and not all of them need to be explored, scientists say.

“The only thing we need to do is make sure we are forward-looking,” Prem says. "Who knows what kind of science people will want to do in the future?"