help article explains that overthinking is the enemy of creativity, and advises to be careful: “In order to do something, we may need to think less. It seems counterintuitive, but I find that sometimes our thoughts can get in the way of the creative process. Sometimes we can work better when we 'disconnect' from the outside world, focusing on what is in front of us. "

The post was written by GPT-3, a huge Open AI neural network with 175 billion parameters trained in almost half a trillion words. UC Berkeley student Liam Porr just wrote the headline and let the algorithm write the text. A " fun experiment " to see if the AI can fool people. Indeed, GPT-3 hit the nerves with this post reaching number one on Hacker News.

So there is a paradox with today's AI. While some of the GPT-3 papers may satisfy the Turing test in convincing people that they are human, they clearly fail on the simplest assignments. Artificial intelligence researcher Gary Marcus askedGPT-2, the predecessor to GPT-3, finish this sentence:

“What happens when you put firewood and logs into the fireplace and then throw a few matches? Usually it will start ... ”

“ Fire ”is what any child will immediately scream. But GPT-2 answer: "Ick" The

experiment failed. Case is closed?

Dark matter of natural language

Human communication is an optimization process. The speaker minimizes the number of utterances necessary to convey his thoughts to the listener. Everything that is overlooked is called common sense. And since the listener has the same common sense as the speaker, he can give meaning to the utterance.

So, by definition, common sense is never written down. As NLU scholar Walid Saba pointed out , we are not saying:

Charles, who is a living young adult who was in graduate school, dropped out of graduate school to join a software company looking for a new employee.

We put it more simply:

Charles dropped out of graduate school to work for a software company

and we assume that our interlocutor already knows:

- You must be alive to attend school or join the company.

- You must be in graduate school to quit.

- The company must have an open position to close it.

Etc. All human utterances are like this, filled with invisible rules of common sense that we never explicitly state. Thus, common sense can be compared with dark matter in physics: it is invisible, but makes up the bulk.

So how, then, can machines be taught artificial common sense? How can they know that we are throwing a match because we want to start a fire?

Artificial Common Sense: The Brute Force Method

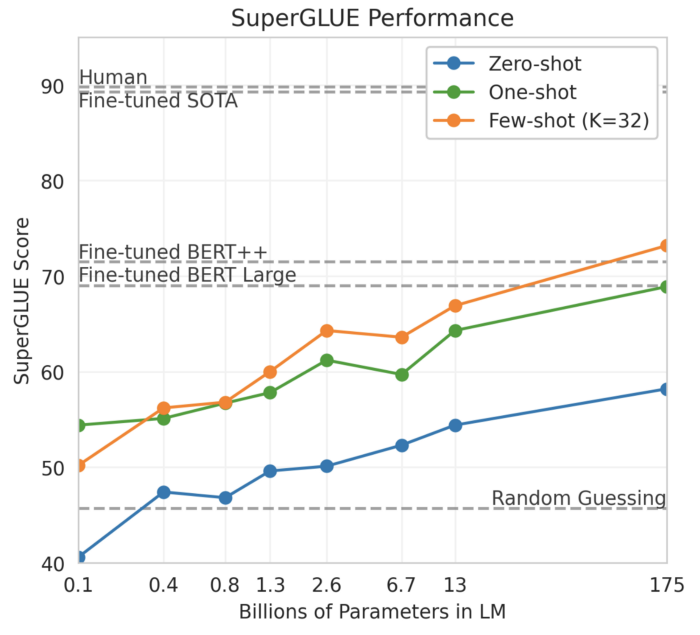

There is reason to believe that we can use brute force in artificial common sense, and that reason is the slope of the curve in the following graph:

GPT-3 Performance on SuperGLUE

This graph from the GPT-3 work " FSL Language Models " shows the performance of the SuperGLUE model as a function of the number of model parameters, with the full GPT-3 model at the far right. SuperGLUE contains some pretty complex semantic tasks, such as Winograd's schemes:

The trophy doesn't fit in the brown suitcase because it's too small.

What's too little?

Answer: a suitcase.

It is noteworthy that at 175 billion parameters, the curve is still growing: the maximum point has not yet been reached. So one hypothesis is that we should be able to build even larger models with trillions or more parameters and eventually artificial common sense will emerge. Let's call this assumption the "brute force" hypothesis.

However, this is just a hypothesis, and we do not know if it is actually true or not. The counter-argument here is that a machine simply cannot learn from something that is not explicitly stated.

Endless rules

If we want to teach common sense to machines, why not just write it all down as rules and then pass those rules to the machine? This is exactly what Douglas Lenat set out to do in the 1980s. He hired computer scientists and philosophers to create the common sense knowledge base known today as Cyc. Today Cyc contains 15 million rules, such as:

1. A bat has wings.

2. Since it has wings, the bat can fly.

3. Since the bat can fly, it can travel from place to place.

The problem with a hardcoded system like Cyc is that the rules are endless: for every rule, there is an exception, an exception from an exception, and so on. Since a bat has wings, it can fly, unless it breaks its wing. This endless loop makes the set of rules more and more complex, making it harder for humans to maintain the memory of a machine, and for machines to maintain it.

So it's no surprise that despite decades of effort, Cyc still doesn't work and may never work. University of Washington professor Pedro Domingos calls Cyc "the biggest failure in the history of artificial intelligence." Oren Etzioni, CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, another critic, remarked in an interview with Wired: "If it worked, people would know it works."

Let's summarize. For "real" AI, we need to create artificial common sense. But there are compelling arguments against the brute force hypothesis. On the other hand, there are compelling arguments against hardcoded rules. What if we combined the best in these approaches?

Hybrid approach

Meet COMET , a transformer-based model developed by University of Washington professor Yejin Choi and her collaborators. The essence of the model is that it learns on the "seed" knowledge base of common sense, and then expands this base, generating new rules based on each new statement. Thus, COMET is a way to "load" artificial common sense. In their article, the researchers write that COMET "often provides new common sense knowledge that evaluators believe to be correct."

As a test, I typed in the text: "Gary puts firewood and logs in the fireplace, and then throws some matches" in the COMET API , and here is part of the output graph:

Some of COMET's inferred graph of COMET's common sense

correctly concludes that Gary * wanted * to light a fire. The system also indicates that "it gets warm as a result of Gary." This sounds much better than GPT-3's answer to the same request in my opinion.

So, is COMET a solution to the artificial common sense problem? This remains to be seen. If, say, COMET achieves human-level performance on SuperGLUE, it will undoubtedly be a breakthrough in the field.

On the other hand, critics might argue that common sense cannot be measured with artificial reference datasets. There is a risk that, after creating such a benchmark dataset, researchers will at some point begin to retrain the model, rendering the benchmark result meaningless. One line of thought is to test AI with the same intelligence tests as humans. For example, researchers Stellan Olsson and staff at the University of Illinois at Chicago suggest testing artificial common sense using IQ tests on young children.

Don't let today's AI fool you

Finally, don't let today's AI fool you. Looking back at the GPT-3 article, I realize that many of its statements are superficial and generalized, such as in the fortune cookie:

It's important to stay open-minded and try new things.

And this superficiality is probably the reason why so many people can be deceived. Ultimately, superficiality hides a lack of true understanding.

- Data Science profession training

- Data Analyst training

- Machine Learning Course

Other professions and courses

- Java-

- Frontend-

- -

- C++

- Unity

- iOS-

- Android-

- «Machine Learning Pro + Deep Learning»

- «Python -»

- JavaScript

- « Machine Learning Data Science»

- DevOps