Using the pipeline in Powershell

The algorithm is simple, the first is the random door generator, then the user choice generator, then the presenter's door opening logic, another user action and statistics counting.

And help us with this is the power tool

ValueFromPipeline

, which allows us to specify the cmdlet one by one, transforming the object step by step. Our pipeline should look like this:

New-Doors | Select-Door | Open-Door | Invoke-UserAction

New-Doors

generates new doors, in the team the

Select-Door

player chooses one of the doors, the

Open-Door

leader opens the door in which there is definitely no goat and which was not chosen by the player, and in

Invoke-UserAction

we simulate different user behavior.

The object describing the door moves from left to right, gradually transforming.

This method of writing code helps to keep it in pieces with clear divisions of responsibility.

Powershell has its own conventions. Including the conventions on the correct naming of functions , they must also be observed and we almost comply with them.

Making doors

Since we are going to simulate the situation, we will also describe the doors in detail.

The door contains either a goat or a car. The door can be chosen by the player or opened by the host.

class Door {

<#

, .

.

#>

[string]$Contains = "Goat"

[bool]$Selected = $false

[bool]$Opened = $false

}

We will place each of the doors in a separate field in a separate class.

class Doors {

<#

, 3

#>

[Door]$DoorOne

[Door]$DoorTwo

[Door]$DoorThree

}

It was possible to put them all the doors in an array, but the more detailed everything is described, the better. By the way, in Powershell 7, classes, their constructors, methods and everything else OOP, which works almost as it should, but more on that another time.

The random door generator looks like this. First, for each door jamb, its own door is generated, and then the generator chooses which one of them the car will stand behind.

function New-Doors {

<#

.

#>

$i = [Doors]::new()

$i.DoorOne = [Door]::new()

$i.DoorTwo = [Door]::new()

$i.DoorThree = [Door]::new()

switch ( Get-Random -Maximum 3 -Minimum 0 ) {

0 {

$i.DoorOne.Contains = "Car"

}

1 {

$i.DoorTwo.Contains = "Car"

}

2 {

$i.DoorThree.Contains = "Car"

}

Default {

Write-Error "Something in door generator went wrong"

break

}

}

return $i

Our pipe looks like this:

New-Doors

The player chooses the door

Now let's describe the initial choice. The player can choose one of three doors. For the purpose of simulating more situations, let the player choose only the first, only the second, only the third, and random door each time.

[Parameter(Mandatory)]

[ValidateSet("First", "Second", "Third", "Random")]

$Principle

To accept arguments from the pipeline, you need to specify a variable in the parameter block that will do this. This is done like this:

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i

You can write

ValueFromPipeline

without

True

.

This is how the finished door selection block looks like:

function Select-Door {

<#

.

#>

Param (

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i,

[Parameter(Mandatory)]

[ValidateSet("First", "Second", "Third", "Random")]

$Principle

)

switch ($Principle) {

"First" {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $true

}

"Second" {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $true

}

"Third" {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $true

}

"Random" {

switch ( Get-Random -Maximum 3 -Minimum 0 ) {

0 {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $true

}

1 {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $true

}

2 {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $true

}

Default {

Write-Error "Something in door selector went wrong"

break

}

}

}

Default {

Write-Error "Something in door selector went wrong"

break

}

}

return $i

Our pipe looks like this:

New-Doors | Select-Door -Principle Random

Leading opens the door

Everything is very simple here. If the door was not chosen by the player and if there is a goat behind it, then change the field

Opened

to

True

. Specifically, in this case, it is

Open

not correct to call the command a word , the called resource is not read, but changed. In such cases, use

Set

, but

Open

leave for clarity.

function Open-Door {

<#

, , .

#>

Param (

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i

)

switch ($false) {

$i.DoorOne.Selected {

if ($i.DoorOne.Contains -eq "Goat") {

$i.DoorOne.Opened = $true

continue

}

}

$i.DoorTwo.Selected {

if ($i.DoorTwo.Contains -eq "Goat") {

$i.DoorTwo.Opened = $true

continue

}

}

$i.DoorThree.Selected {

if ($i.DoorThree.Contains -eq "Goat") {

$i.DoorThree.Opened = $true

continue

}

}

}

return $i

To make our simulation more convincing, we "open" this door by changing the .opened field to

$true

instead of removing the object from the door array.

Do not forget about

continue

switches, the comparison does not stop after the first match.

Coninue

exits the switch and continues to execute the script, and the operator

break

in the switch terminates the script.

Add one more function to the pipe, it now looks like this:

New-Doors | Select-Door -Principle Random | Open-Door

The player changes his choice

The player either changes the door or does not change it. In the parameter block, we only have a variable from the pipe and a boolean argument.

Use the word

Invoke

in the names of such functions, because it

Invoke

means calling a synchronous operation, and

Start

asynchronous, follow the conventions and recommendations.

function Invoke-UserAction {

<#

, .

#>

Param (

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i,

[Parameter(Mandatory)]

[bool]$SwitchDoor

)

if ($true -eq $SwitchDoor) {

switch ($false) {

$i.DoorOne.Opened {

if ( $i.DoorOne.Selected ) {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $false

}

else {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $true

}

}

$i.DoorTwo.Opened {

if ( $i.DoorTwo.Selected ) {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $false

}

else {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $true

}

}

$i.DoorThree.Opened {

if ( $i.DoorThree.Selected ) {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $false

}

else {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $true

}

}

}

}

return $i

In the operators of branching and comparison, the system and static variables must be specified first. Probably, there may be difficulties with converting one object to another, but the author did not encounter such difficulties when he wrote in a different way before.

Another function in the pipeline.

New-Doors | Select-Door -Principle Random | Open-Door | Invoke-UserAction -SwitchDoor $True

The advantage of this writing approach is clear, because it has never been so convenient to split code into parts with a clear separation of functions.

Player behavior

How often the player changes the door. There are 5 lines of behavior:

Never

- the player never changes his choiceFifty-Fifty

- 50 to 50. The number of simulations is divided into two passes. The first pass the player does not change the door, the second pass changes.Random

- in each new simulation, the player flips a coinAlways

- the player always changes his choice.Ration

- the player changes his choice in N% of cases.

switch ($SwitchDoors) {

"Never" {

0..$Count | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $false

}

continue

}

"FiftyFifty" {

$Fifty = [math]::Round($Count / 2)

0..$Fifty | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $false

}

0..$Fifty | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $true

}

continue

}

"Random" {

0..$Count | ForEach-Object {

[bool]$Random = Get-Random -Maximum 2 -Minimum 0

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $Random

}

continue

}

"Always" {

0..$Count | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $true

}

continue

}

"Ratio" {

$TrueRatio = $Ratio / 100 * $Count

$FalseRatio = $Count - $TrueRatio

0..$TrueRatio | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $true

}

0..$FalseRatio | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $false

}

continue

}

}

ForEach-Object

in Powershell 7 it works much faster than a loop

for

, plus it can be parallelized, so it is used here instead of a loop

for

.

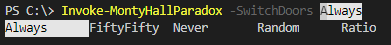

Styling the cmdlet

Now you need to correct the cmdlet. First of all, you need to do the validation of the incoming arguments. The bonus is not only that a person cannot enter an invalid argument in the field, but also a list of all available arguments appears in the prompts.

This is how the code in the parameter block looks like:

param (

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false,

HelpMessage = "How often the player changes his choice.")]

[ValidateSet("Never", "FiftyFifty", "Random", "Always", "Ratio")]

$SwitchDoors = "Random"

)

This is the hint:

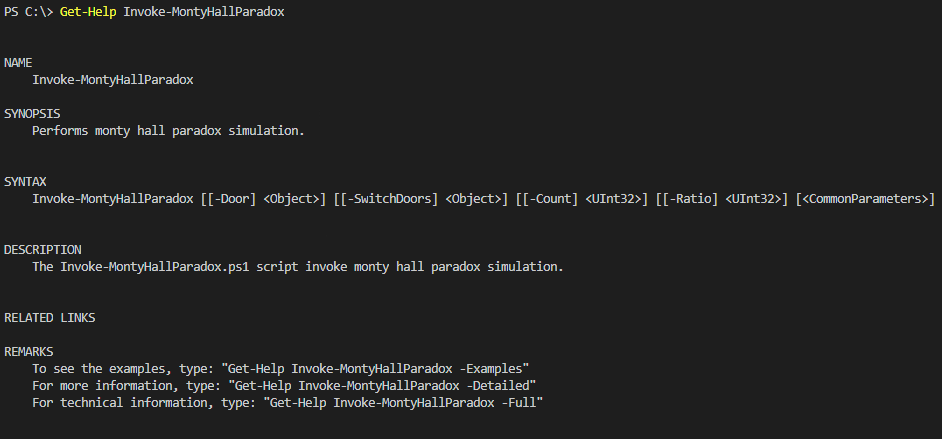

Before the parameter block can be done

comment based help

. This is what the code looks like before the parameter block:

<#

.SYNOPSIS

Performs monty hall paradox simulation.

.DESCRIPTION

The Invoke-MontyHallParadox.ps1 script invoke monty hall paradox simulation.

.PARAMETER Door

Specifies door the player will choose during the entire simulation

.PARAMETER SwitchDoors

Specifies principle how the player changes his choice.

.PARAMETER Count

Specifies how many times to run the simulation.

.PARAMETER Ratio

If -SwitchDoors Ratio, specifies how often the player changes his choice. As a percentage."

.INPUTS

None. You cannot pipe objects to Update-Month.ps1.

.OUTPUTS

None. Update-Month.ps1 does not generate any output.

.EXAMPLE

PS> Invoke-MontyHallParadox -SwitchDoors Always -Count 10000

#>

This is how the prompt looks like:

Running the simulation

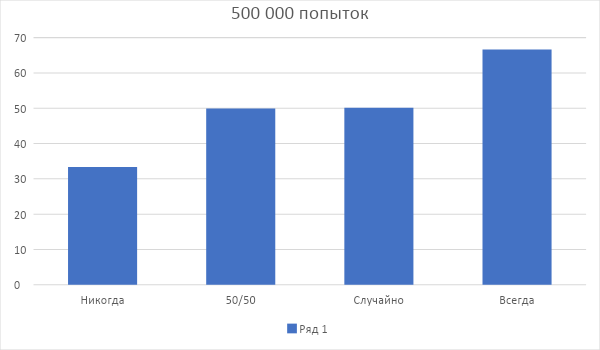

Simulation results:

If a person never changes his choice, then he wins 33.37% of the time.

In the case of two passes, in half of which we refuse to change our choice, the chances of winning are 49.9134%, which is very close to exactly 50%.

In the case of a coin toss, nothing changes, the chance of winning remains around 50.131%.

Well, if the player always changes his choice, the chance of winning rises to 66.6184%, in other words, boring and nothing new.

Performance:

In terms of performance. The script doesn't seem to be optimal.

String

instead

Bool

, many different functions with a switch inside, passing an object to each other, but nevertheless, here are the results

Measure-Command

for this script and a script from another author .

The comparison was carried out on two systems, pwsh 7.1 was everywhere, 100,000 passes.

▍I5-5200u

This algorithm:

Days : 0 Hours : 0 Minutes : 0 Seconds : 4 Milliseconds : 581 Ticks : 45811819 TotalDays : 5,30229386574074E-05 TotalHours : 0,00127255052777778 TotalMinutes : 0,0763530316666667 TotalSeconds : 4,5811819 TotalMilliseconds : 4581,1819

That algorithm:

Days : 0 Hours : 0 Minutes : 0 Seconds : 5 Milliseconds : 104 Ticks : 51048392 TotalDays : 5,9083787037037E-05 TotalHours : 0,00141801088888889 TotalMinutes : 0,0850806533333333 TotalSeconds : 5,1048392 TotalMilliseconds : 5104,8392

▍I9-9900K

This algorithm:

Days : 0 Hours : 0 Minutes : 0 Seconds : 1 Milliseconds : 891 Ticks : 18917629 TotalDays : 2,18954039351852E-05 TotalHours : 0,000525489694444444 TotalMinutes : 0,0315293816666667 TotalSeconds : 1,8917629 TotalMilliseconds : 1891,7629

That algorithm:

Days : 0 Hours : 0 Minutes : 0 Seconds : 1 Milliseconds : 954 Ticks : 19543236 TotalDays : 2,26194861111111E-05 TotalHours : 0,000542867666666667 TotalMinutes : 0,03257206 TotalSeconds : 1,9543236 TotalMilliseconds : 1954,3236

63ms advantage, but the results are still very strange considering how many times the script compares strings.

The author hopes that this article will serve as a convincing example for those who believe that the odds are always 50 to 50, but you can read the code under this spoiler.

The whole code

class Doors {

<#

, 3

#>

[Door]$DoorOne

[Door]$DoorTwo

[Door]$DoorThree

}

class Door {

<#

, .

.

#>

[string]$Contains = «Goat»

[bool]$Selected = $false

[bool]$Opened = $false

}

function New-Doors {

<#

.

#>

$i = [Doors]::new()

$i.DoorOne = [Door]::new()

$i.DoorTwo = [Door]::new()

$i.DoorThree = [Door]::new()

switch ( Get-Random -Maximum 3 -Minimum 0 ) {

0 {

$i.DoorOne.Contains = «Car»

}

1 {

$i.DoorTwo.Contains = «Car»

}

2 {

$i.DoorThree.Contains = «Car»

}

Default {

Write-Error «Something in door generator went wrong»

break

}

}

return $i

}

function Select-Door {

<#

.

#>

Param (

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i,

[Parameter(Mandatory)]

[ValidateSet(«First», «Second», «Third», «Random»)]

$Principle

)

switch ($Principle) {

«First» {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $true

continue

}

«Second» {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $true

continue

}

«Third» {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $true

continue

}

«Random» {

switch ( Get-Random -Maximum 3 -Minimum 0 ) {

0 {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $true

continue

}

1 {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $true

continue

}

2 {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $true

continue

}

Default {

Write-Error «Something in selector generator went wrong»

break

}

}

continue

}

Default {

Write-Error «Something in door selector went wrong»

break

}

}

return $i

}

function Open-Door {

<#

, , .

#>

Param (

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i

)

switch ($false) {

$i.DoorOne.Selected {

if ($i.DoorOne.Contains -eq «Goat») {

$i.DoorOne.Opened = $true

continue

}

}

$i.DoorTwo.Selected {

if ($i.DoorTwo.Contains -eq «Goat») {

$i.DoorTwo.Opened = $true

continue

}

}

$i.DoorThree.Selected {

if ($i.DoorThree.Contains -eq «Goat») {

$i.DoorThree.Opened = $true

continue

}

}

}

return $i

}

function Invoke-UserAction {

<#

, .

#>

Param (

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i,

[Parameter(Mandatory)]

[bool]$SwitchDoor

)

if ($true -eq $SwitchDoor) {

switch ($false) {

$i.DoorOne.Opened {

if ( $i.DoorOne.Selected ) {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $false

}

else {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $true

}

}

$i.DoorTwo.Opened {

if ( $i.DoorTwo.Selected ) {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $false

}

else {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $true

}

}

$i.DoorThree.Opened {

if ( $i.DoorThree.Selected ) {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $false

}

else {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $true

}

}

}

}

return $i

}

function Get-Win {

Param (

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i

)

switch ($true) {

($i.DoorOne.Selected -and $i.DoorOne.Contains -eq «Car») {

return $true

}

($i.DoorTwo.Selected -and $i.DoorTwo.Contains -eq «Car») {

return $true

}

($i.DoorThree.Selected -and $i.DoorThree.Contains -eq «Car») {

return $true

}

default {

return $false

}

}

}

function Invoke-Simulation {

param (

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false,

HelpMessage = «Which door the player will choose during the entire simulation.»)]

[ValidateSet(«First», «Second», «Third», «Random»)]

$Door = «Random»,

[bool]$SwitchDoors

)

return New-Doors | Select-Door -Principle $Door | Open-Door | Invoke-UserAction -SwitchDoor $SwitchDoors | Get-Win

}

function Invoke-MontyHallParadox {

<#

.SYNOPSIS

Performs monty hall paradox simulation.

.DESCRIPTION

The Invoke-MontyHallParadox.ps1 script invoke monty hall paradox simulation.

.PARAMETER Door

Specifies door the player will choose during the entire simulation

.PARAMETER SwitchDoors

Specifies principle how the player changes his choice.

.PARAMETER Count

Specifies how many times to run the simulation.

.PARAMETER Ratio

If -SwitchDoors Ratio, specifies how often the player changes his choice. As a percentage."

.INPUTS

None. You cannot pipe objects to Update-Month.ps1.

.OUTPUTS

None. Update-Month.ps1 does not generate any output.

.EXAMPLE

PS> Invoke-MontyHallParadox -SwitchDoors Always -Count 10000

#>

param (

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false,

HelpMessage = «Which door the player will choose during the entire simulation.»)]

[ValidateSet(«First», «Second», «Third», «Random»)]

$Door = «Random»,

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false,

HelpMessage = «How often the player changes his choice.»)]

[ValidateSet(«Never», «FiftyFifty», «Random», «Always», «Ratio»)]

$SwitchDoors = «Random»,

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false,

HelpMessage = «How many times to run the simulation.»)]

[uint32]$Count = 10000,

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false,

HelpMessage = «How often the player changes his choice. As a percentage.»)]

[uint32]$Ratio = 30

)

[uint32]$Win = 0

switch ($SwitchDoors) {

«Never» {

0..$Count | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $false

}

continue

}

«FiftyFifty» {

$Fifty = [math]::Round($Count / 2)

0..$Fifty | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $false

}

0..$Fifty | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $true

}

continue

}

«Random» {

0..$Count | ForEach-Object {

[bool]$Random = Get-Random -Maximum 2 -Minimum 0

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $Random

}

continue

}

«Always» {

0..$Count | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $true

}

continue

}

«Ratio» {

$TrueRatio = $Ratio / 100 * $Count

$FalseRatio = $Count — $TrueRatio

0..$TrueRatio | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $true

}

0..$FalseRatio | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $false

}

continue

}

}

Write-Output («Player won in » + $Win + " times out of " + $Count)

Write-Output («Whitch is » + ($Win / $Count * 100) + "%")

return $Win

}

#Invoke-MontyHallParadox -SwitchDoors Always -Count 500000

<#

, 3

#>

[Door]$DoorOne

[Door]$DoorTwo

[Door]$DoorThree

}

class Door {

<#

, .

.

#>

[string]$Contains = «Goat»

[bool]$Selected = $false

[bool]$Opened = $false

}

function New-Doors {

<#

.

#>

$i = [Doors]::new()

$i.DoorOne = [Door]::new()

$i.DoorTwo = [Door]::new()

$i.DoorThree = [Door]::new()

switch ( Get-Random -Maximum 3 -Minimum 0 ) {

0 {

$i.DoorOne.Contains = «Car»

}

1 {

$i.DoorTwo.Contains = «Car»

}

2 {

$i.DoorThree.Contains = «Car»

}

Default {

Write-Error «Something in door generator went wrong»

break

}

}

return $i

}

function Select-Door {

<#

.

#>

Param (

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i,

[Parameter(Mandatory)]

[ValidateSet(«First», «Second», «Third», «Random»)]

$Principle

)

switch ($Principle) {

«First» {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $true

continue

}

«Second» {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $true

continue

}

«Third» {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $true

continue

}

«Random» {

switch ( Get-Random -Maximum 3 -Minimum 0 ) {

0 {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $true

continue

}

1 {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $true

continue

}

2 {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $true

continue

}

Default {

Write-Error «Something in selector generator went wrong»

break

}

}

continue

}

Default {

Write-Error «Something in door selector went wrong»

break

}

}

return $i

}

function Open-Door {

<#

, , .

#>

Param (

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i

)

switch ($false) {

$i.DoorOne.Selected {

if ($i.DoorOne.Contains -eq «Goat») {

$i.DoorOne.Opened = $true

continue

}

}

$i.DoorTwo.Selected {

if ($i.DoorTwo.Contains -eq «Goat») {

$i.DoorTwo.Opened = $true

continue

}

}

$i.DoorThree.Selected {

if ($i.DoorThree.Contains -eq «Goat») {

$i.DoorThree.Opened = $true

continue

}

}

}

return $i

}

function Invoke-UserAction {

<#

, .

#>

Param (

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i,

[Parameter(Mandatory)]

[bool]$SwitchDoor

)

if ($true -eq $SwitchDoor) {

switch ($false) {

$i.DoorOne.Opened {

if ( $i.DoorOne.Selected ) {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $false

}

else {

$i.DoorOne.Selected = $true

}

}

$i.DoorTwo.Opened {

if ( $i.DoorTwo.Selected ) {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $false

}

else {

$i.DoorTwo.Selected = $true

}

}

$i.DoorThree.Opened {

if ( $i.DoorThree.Selected ) {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $false

}

else {

$i.DoorThree.Selected = $true

}

}

}

}

return $i

}

function Get-Win {

Param (

[parameter(ValueFromPipeline)]

[Doors]$i

)

switch ($true) {

($i.DoorOne.Selected -and $i.DoorOne.Contains -eq «Car») {

return $true

}

($i.DoorTwo.Selected -and $i.DoorTwo.Contains -eq «Car») {

return $true

}

($i.DoorThree.Selected -and $i.DoorThree.Contains -eq «Car») {

return $true

}

default {

return $false

}

}

}

function Invoke-Simulation {

param (

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false,

HelpMessage = «Which door the player will choose during the entire simulation.»)]

[ValidateSet(«First», «Second», «Third», «Random»)]

$Door = «Random»,

[bool]$SwitchDoors

)

return New-Doors | Select-Door -Principle $Door | Open-Door | Invoke-UserAction -SwitchDoor $SwitchDoors | Get-Win

}

function Invoke-MontyHallParadox {

<#

.SYNOPSIS

Performs monty hall paradox simulation.

.DESCRIPTION

The Invoke-MontyHallParadox.ps1 script invoke monty hall paradox simulation.

.PARAMETER Door

Specifies door the player will choose during the entire simulation

.PARAMETER SwitchDoors

Specifies principle how the player changes his choice.

.PARAMETER Count

Specifies how many times to run the simulation.

.PARAMETER Ratio

If -SwitchDoors Ratio, specifies how often the player changes his choice. As a percentage."

.INPUTS

None. You cannot pipe objects to Update-Month.ps1.

.OUTPUTS

None. Update-Month.ps1 does not generate any output.

.EXAMPLE

PS> Invoke-MontyHallParadox -SwitchDoors Always -Count 10000

#>

param (

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false,

HelpMessage = «Which door the player will choose during the entire simulation.»)]

[ValidateSet(«First», «Second», «Third», «Random»)]

$Door = «Random»,

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false,

HelpMessage = «How often the player changes his choice.»)]

[ValidateSet(«Never», «FiftyFifty», «Random», «Always», «Ratio»)]

$SwitchDoors = «Random»,

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false,

HelpMessage = «How many times to run the simulation.»)]

[uint32]$Count = 10000,

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false,

HelpMessage = «How often the player changes his choice. As a percentage.»)]

[uint32]$Ratio = 30

)

[uint32]$Win = 0

switch ($SwitchDoors) {

«Never» {

0..$Count | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $false

}

continue

}

«FiftyFifty» {

$Fifty = [math]::Round($Count / 2)

0..$Fifty | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $false

}

0..$Fifty | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $true

}

continue

}

«Random» {

0..$Count | ForEach-Object {

[bool]$Random = Get-Random -Maximum 2 -Minimum 0

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $Random

}

continue

}

«Always» {

0..$Count | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $true

}

continue

}

«Ratio» {

$TrueRatio = $Ratio / 100 * $Count

$FalseRatio = $Count — $TrueRatio

0..$TrueRatio | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $true

}

0..$FalseRatio | ForEach-Object {

$Win += Invoke-Simulation -Door $Door -SwitchDoors $false

}

continue

}

}

Write-Output («Player won in » + $Win + " times out of " + $Count)

Write-Output («Whitch is » + ($Win / $Count * 100) + "%")

return $Win

}

#Invoke-MontyHallParadox -SwitchDoors Always -Count 500000