I will assemble a computer based on Pentium 4 according to the best recommendations of 15 years ago a little later (advice on correct assembly in the spirit of the times is welcome). This article is an attempt to timestamp the Pentium 4 era, to determine what was wrong with this processor and what was wrong. Plus the results of experiments with real hardware, some impressions from the present and memories from the past. And benchmarks, of course, where without them.

I keep a diary of a collector of old pieces of iron in Telegram .

Willamette and RDRAM

- Announcement : November 2000, 20 years ago

- Process technology : 180 nanometers

- Frequency : 1.3-2.0 GHz

- TDP : 50-75 Watts

- L2 cache size : 256 KB

- FSB frequency : 100 MHz, 3200 MB / s

Special thanks to the IXBT website for keeping the archive of articles with original links. Shortly before the official announcement, there was published (in two parts ) a detailed description of the new NetBurst architecture based on the Pentium 4 and a comparison with the previous Pentium III processors based on the P6 architecture. Important innovations in NetBurst are a "long" computational pipeline of 20 levels, support for the new SSE2 instruction set, a system bus that performs four transactions per cycle, and the operation of arithmetic logic blocks at a doubled frequency. On November 20, 2000, processors with a frequency of 1.4 and 1.5 GHz are released. For comparison, the maximum frequency of the Pentium 3 Coppermine processor at that time was 1.13 GHz. On the same day, IXBT publishesphotos of the processor and test results with the general verdict: ¯ \ _ (ツ) _ / ¯.

Pentium 4 1.4 is compared with Pentium 3 1GHz and these two systems show approximately the same result - in one benchmark the old processor is slightly ahead, in the other - the new one has a slight advantage. In general, it was not very clear where the breakthrough was. Obviously, the Pentium 4 was faster only in the audio compression test. In the first year of its life, the new flagship of Intel was a dubious choice, especially since the third Pentium in 2001 was re-released on a new 130nm technical process and the frequency was brought to 1.4 GHz. A feature of the Netburst architecture and that very "extra-long" pipeline is the potential for further increase in frequency. In August 2001, the frequency of Pentium 4 processors was brought up to 2 GHz. As for the advantage in benchmarks and real software,then, as a rule, everything depended on the desire of the developers to optimize the software for the new architecture.

In the same August 2001, I buy a computer based on Pentium III, having a rather vague idea of what is generally going on in the personal systems market. I am guided by advertising posters (Whatman paper, felt-tip pens) on the Savelovsky market, which, as it were, is not an objective source of information. One thing is clear: I cannot afford the "fourth pentium" with all my desire - it is too expensive. My previous PC was a 386, and any new hardware is better compared to it. The incomprehensible RDRAM memory with which the P4 went on sale a year earlier is embarrassing: the press writes about excessive heating and small advantages over SDRAM memory. In 2020, the combination of a processor on a "dead-end" architecture with a dead-end memory standard is a worthy reason to build a retro PC, but I have other priorities.

Northwood

- Announced : January 2002, 18 years ago

- Process technology : 130 nanometers

- Frequency : 1.6-3.4 GHz

- TDP : 38-80 Watts

- L2 cache size : 512 KB

- FSB frequency : 100-200 MHz, 3200-6400 MB / s

With frequencies of 2 GHz or more, the second generation Pentium 4 should be compared not with the aging Pentium 3, but with the competitor from AMD, the Athlon XP processor. AMD consistently lagged behind Intel in the maximum frequency of its processors, which did not prevent them from showing decent results in benchmarks. It was difficult to convince the average consumer, accustomed to evaluating computers by processor frequency, that everything is somewhat more complicated. AMD actively uses Performance Rating - this is when the 2100 MHz processor is called "Ahtlon XP 3000+". This rating alluded to the frequency of a Pentium 4 processor with similar performance, although AMD has never officially acknowledged this connection.

With Northwood processors, Intel is dropping Rambus DRAM. New chipsets work with DDR SDRAM. The frequency of the system bus is growing, and with it the speed of working with RAM: in May 2002 processors with FSB frequency of 133 MHz were released, a year later - 200 MHz. In November 2002, another innovation appeared: Hyper-Threading technology, which allows additional loading of the computational pipeline due to the virtual second processor core. In my computer reality of the same year, for some time I generally remain without a computer, and then I assemble an outdated, but quite suitable for any task, a desktop based on Pentium II.

In December 2020, I buy a set of Asus P4PE motherboard, Pentium 4 Northwood 2.4 GHz processor ( SL6EU, FSB 133 MHz) and a gigabyte of DDR RAM.

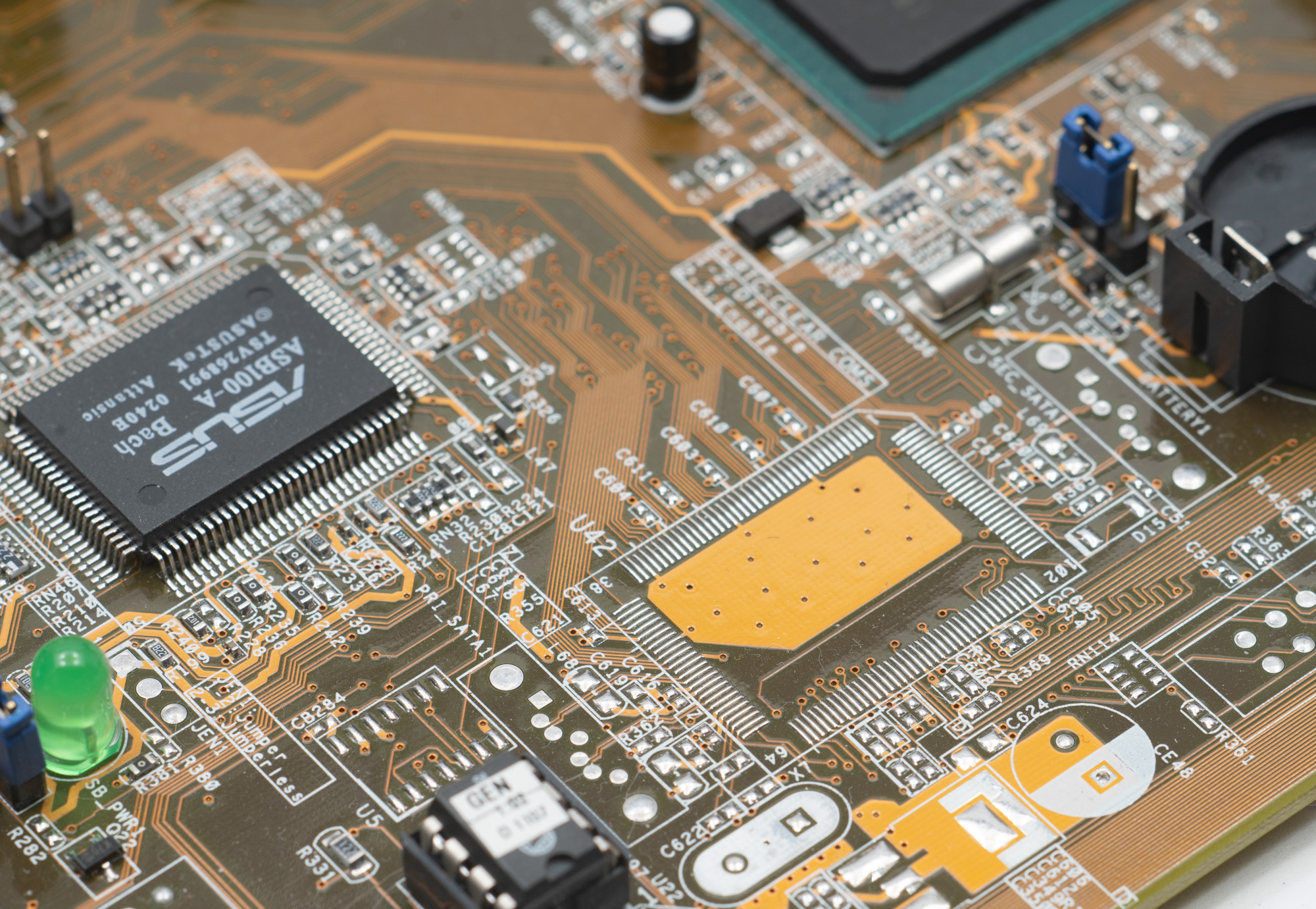

This is not the most budget motherboard, but it is not “premium” either. I845 chipset, onboard audio and 100Mbps network interface. The board has a place for a SATA controller, but it is not unsoldered, so I connect a 320 gigabyte IDE hard drive to the board.

The slot for a video card is of the AGP 4x standard, and there are none in my collection yet. But there is a strange, but working solution: GeForce 6200 512 MB with a PCI slot and passive cooling. The blue slot on the board is a place for installing the WiFi module, which Asus sells to the board.

I did not set myself the task of conducting a scientific study of the performance of the old processor: for this I would have to obtain many variants of motherboards and CPUs. But I wanted to make an impression, so I'll choose a relatively modern benchmark Geekbench 4. Here are the results:

The processor does not yet support Hyper-Threading, the results in the multitasking test are slightly worse than in the single-tasking one. For now, let's remember these numbers, and at the same time note the time frame: mid-2002. In any case, this is a good progress in two years: we started with 1.7 GHz, and at the end of 2002 we already crossed the 3 GHz line. Already in 2000, technical publications write about reaching a frequency of 10 gigahertz by 2005. I have not found an official Intel statement with such a figure, apparently, the forecast was announced behind the scenes. But most likely the plan was this: if the technological process of 130 nanometers allows 3 gigahertz, then we will make six at 90nm, and so on. Simple and straightforward scheme for increasing productivity.

Hot Prescott

- Announcement: February 2004, 16 years ago

- Process technology : 90 nanometers

- Frequency : 2.4-3.8 GHz

- TDP : 84-115 Watts

- L2 cache size : 1024-2048 KB

- Front side bus frequency : 133-200 MHz , 4256-6400 MB / s (rare models up to 266 MHz)

You won't be able to just take and change an Intel processor for a new one in the early 2000s. First, Socket 423 is changed to Socket 478. Both Northwood and Prescott processors are produced in this design, but Prescott does not work in my early Asus P4PE motherboard, although it supports the system bus frequency of 200 MHz. AMD is doing better with backward compatibility. In February 2004 IXBT disassemblesinnovations in Pentium 4 Prescott: there is not only a new technical process. Increased conveyor length from 20 to 31 steps in an attempt to find overclocking potential. The cache of the second level has been increased to one megabyte, processors with two megabytes of cache will appear later. Introduced new SSE3 instructions. EM64T technology is added - 64-bit operating systems can now be installed on processors. AMD is moving 64-bit early, and then it will be the first to release consumer dual-core CPUs. The same article compares the processor with Northwood of the same frequency and AMD Ahtlon 64 3400+. The results are the same as in 2000: somewhere better than its predecessor, somewhere worse. General verdict: " Prescott core is generally slower than Northwood ".

If the situation of 2000-2002 had repeated itself, it would not have become a problem: we are quickly reaching the 4-5 gigahertz line, and leaving old processors and competitors far behind. But no: even according to the official specifications, Prescott is very hot. And the frequency at the end of 2004 was brought to 3.8 gigahertz: this record will be delayed for several years. The planned Pentium 4 580 with a frequency of 4 GHz was canceled. No 10 gigahertz ever happened. I would like to say: we ran into physical limitations, but this is not entirely true. Until the early 2010s, the Pentium 4 was a favorite of overclockers. On the HWBot site, the Intel Celeron D 352 based on the NetBurst architecture is still in 5th place in terms of the maximum frequency - 8543 megahertz. A full-fledged Pentium 4 was able to overclock up to 8179 megahertz.But overclocking and the ability to solve user problems are completely different things. The user does not need liquid nitrogen cooling, he does not want to learn how to remove the thermal cover from the processor. But the plan was so simple.

At the end of 2004, another event happened: Intel processors switched to the new Socket 775. For the first time, the processors were deprived of legs, they moved to the mating socket on the motherboard. Socket 775 has been on the market for a surprisingly long time, and now it is more likely associated with the Intel Core 2 platform. I buy another set: an Asus P5GD1 motherboard, a Pentium 4 processor and three gigabytes of RAM with four DDR1 modules. This is almost modernity: a PCI Express slot for a video card, built-in sound with the ability to connect multi-channel acoustics (it was fashionable in the mid-2000s), a slightly more convenient cooler with four mounts. The board is again budget, but there is already SATA, an additional IDE controller, connectors for USB and audio ports on the front panel. No overclocking options, none. But we don't need it yet.

The board came with a 2006 Intel Pentium 4 generation Cedar Mill processor. This is the "last forgiveness" of the NetBurst architecture of AKA "Prescott of a normal person": a 65 nanometer process technology, 2 megabytes of cache memory, TDP within a reasonable range, frequencies from 3 to 3.6 GHz. But I mine the real, that very fiery Prescott with a frequency of 3.4 gigahertz. At the same time, I will change the video card to a "normal" GeForce 6800. It has a terribly evil small cooler, which I would like to immediately change for something more decent.

Let's see what the processors show in the benchmarks:

Pentium 4 3.4 Prescott :

Pentium 4 3.2 Cedar Mill :

Game

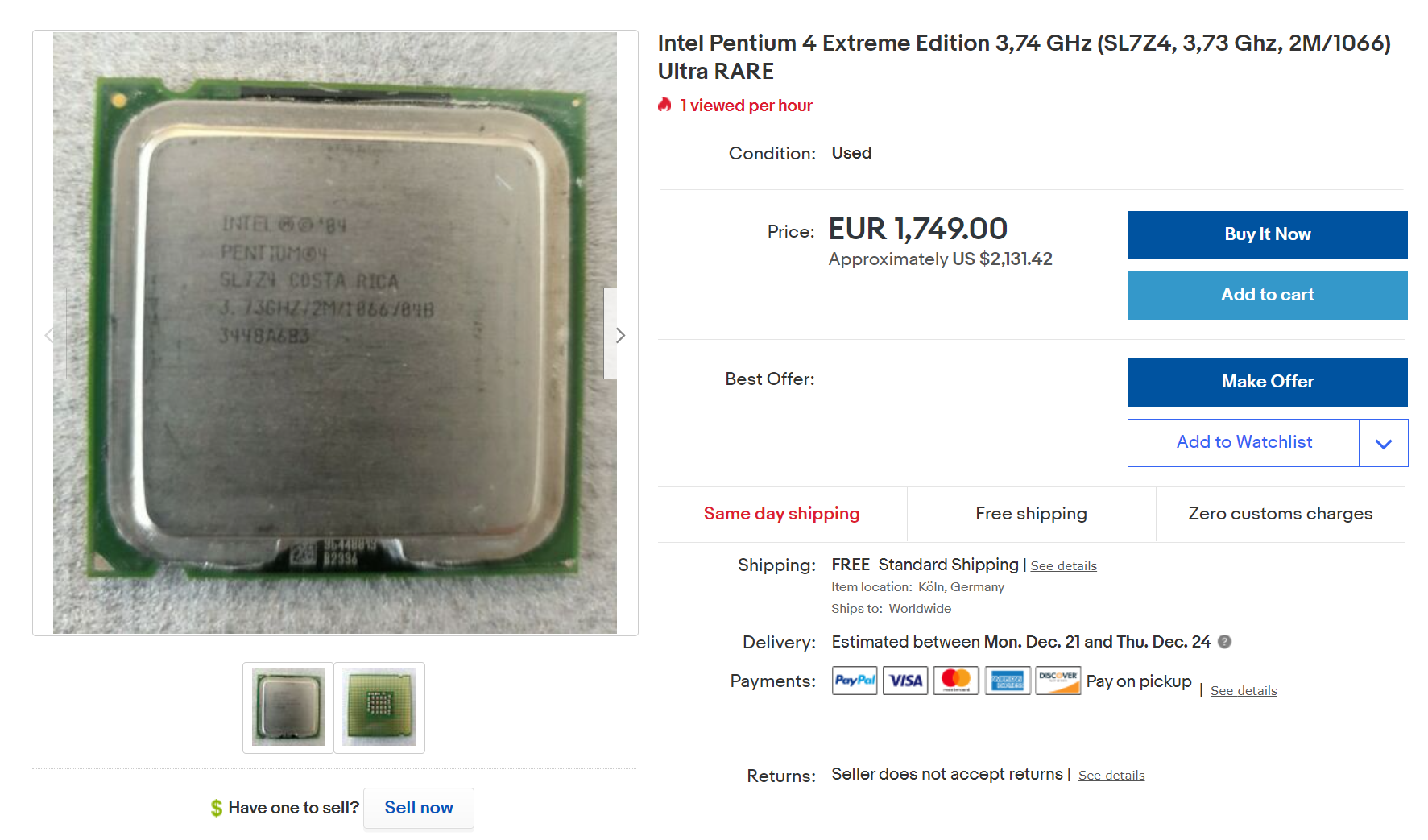

When assembling a Pentium 4 as a retrosystem, one wants to portray something like that, and find, if not the most powerful, then some rare processor of this model. The choice is great. First, we can mention Intel Pentium D: later development of Prescott in dual-core design. It can be used to build the hottest Pentium 4 with an official TDP of 130 watts for models with a frequency of 3.2-3.6 gigahertz. It will also be as close as possible to modern computers, and at the same time it will warm your office well in winter. Secondly, this is the same Pentium 4 with a historically maximum frequency of 3.8 GHz. Finally, there is the Pentium 4 Extreme Edition series: they appeared every time AMD was ready to present its next flagship, and Intel tried to outrun its competitor by at least half a centimeter. Early P4EEs were based on the 130nm Gallatin core borrowed from Intel Xeon. Of particular interest are Pentium 4 EE with 266 MHz system bus - there were only two of them. Finding any extreme Pentium isn't easy enoughthey retail for ~ $ 1,300 compared to ~ $ 500 for a "regular top". There were few people willing to exchange money for heat. The proof of this is this lot on eBay:

I probably won't chase rare modifications - it doesn't make much sense anyway. I plan to stay with the late Pentium 4 with normal heat dissipation, and perhaps even try a moderate overclocking - this way it will most likely be possible to achieve the same 3.8 GHz (or high FSB bandwidth) much easier and cheaper. But this is not certain, you may have to suffer.

Everything repeats itself.

I thought for a long time what to compare the performance of Pentium 4. When I examined the Sony VAIO TZ subnotebook 2007, I had the assumption that its performance corresponds to that of the Pentium 4. And so it happened: an economical, light and thin laptop shows 778 points in Geekbench in a single-threaded test and 1241 points in a "multi-core". The first result is slightly better than the Pentium 4 2.4 of 2002. The second one is higher than in Prescott 3.4, while power consumption is incomparable. Another interesting comparison from my collection is the IBM ThinkPad T40 laptop with Pentium M 755 2GHz 2004 processor. Its Geekbench score is 876 points, which roughly corresponds to the Pentium 4 of the same year of release with a frequency of 2.8-3 GHz. It was then that it finally became clear that it was not only a matter of the processor frequency: it would be great to continue increasing it endlessly, this is understandable for buyers. But it didn't work out.

Another "game" is an adapter from Socket 479 (mobile Pentium M) to Socket 478 (desktop motherboards). Overclocking such a semi-stationary PC showed excellent results. My slowly outdated but still modern ThinkPad T480 laptop with 8th Gen Core i7 scores more than 5000 points in Geekbench 4, at a maximum frequency of 4 GHz. It would be correct to compare with the results of good desktop processors, and this approximately 10 thousand points. Performance growth 10 times (per core, and there are now many of them) from 2005 to 2020. Compare that to a 300x increase (by my own measurements ) from 1992 to 2001.

In 2005, Intel “had problems”: something went wrong with the NetBurst architecture, competitors are advancing, both external and internal - in the form of the very mobile Pentium M, the heir to Pentium Pro processors from the nineties. In July 2006, the company released Intel Core 2 processors, which also have the ancient P6 architecture in their relatives. The starting frequency is ridiculous by the standards of Netburst - 1.87-2.67 GHz, but the performance is higher, the power consumption is noticeably lower. The first quad-core processors are released in 2007. In 2005, I bought my own Pentium 4-based computer, for which my tech-savvy acquaintances criticize me - I bought it in vain, too late. And they were, of course, right.

Although Pentium 4s became a dead-end branch of processor design, providing questionable performance gains from generation to generation, it was during this time that computers finally took on their modern features. Have become truly multimedia, cracking down on video and music content without any problems. The volumes of hard drives have grown from units to hundreds of gigabytes, and the first solid-state drives have appeared. Finally, in the era of my retro video card GeForce 6800, the iconic games were released that I personally still play: Half-Life 2, Far Cry, GTA San Andreas. Not only the capabilities of the processor are important, but also the performance of all peripherals, the availability of high-speed Internet. The rapid development of the entire computer ecosystem, still revolving around a personal computer, more often a desktop computer than a portable one, happened just at the beginning of the 2000s.This is an interesting era.

About love. In my Telegram channel, I conducted a poll about the subjective attitude towards Pentium 4. And the majority still classified it as “nice retro”. As time goes on, soon systems based on Core 2 will move into this category, and in fact they even run the modern web. And one more thing: Intel still has “problems”. And with the transition to a new technical process, and an increase in productivity compared to previous generations. All this was already 15 years ago, and then Intel did it. True, then the traditional for x86 markets of desktops and servers was not threatened by the ARM architecture.

I am starting to enjoy the construction of a retro computer from retro components. In the next article: a slightly more elite Pentium 4 configuration, more benchmarks, and an attempt to bring back my 2005.