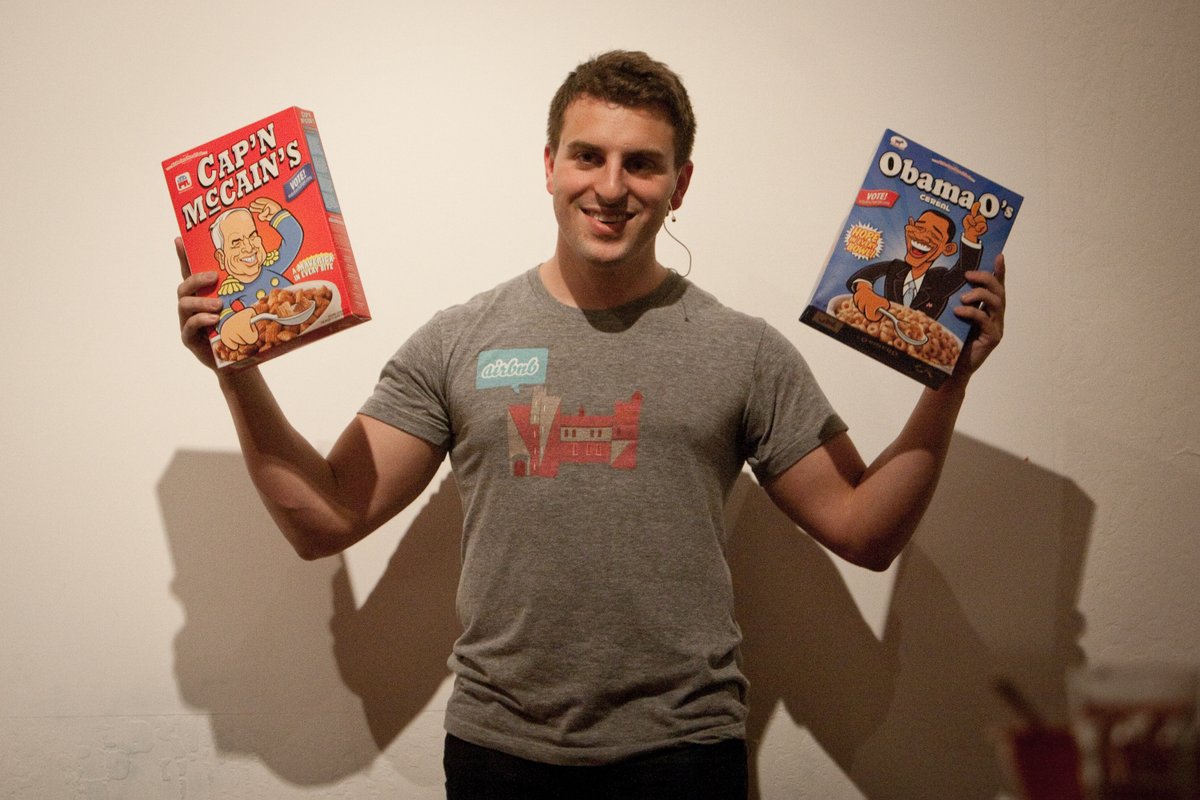

In the early stages, to raise money, the founders sold oatmeal with images of presidential candidates. Both candidates.

Paul Graham, Founder of Y Combinator: We're celebrating the IPO of Airbnb, and to provide guidance to future founders of similarly cool startups, I thought it might be helpful to explain what's special about Airbnb.

The most special thing about the early Airbnb founders was their earnest. In the beginning, they had lousy results and we immediately realized this in the interview. Sometimes, after interviewing a startup, we didn't know what to do and we had to discuss it. On other occasions, we just looked at each other and smiled. The Airbnb interview was just that. We didn't even like their idea. They didn't have users, they didn't have growth. But the founders seemed so full of energy that it was impossible not to fall in love with them.

This first impression did not disappoint. While studying at YC, Brian Chesky was nicknamed "The Tasmanian Devil" because, like the cartoon character, he seemed like a hurricane of energy.

All three were like that. During YC, no one ever worked harder than Airbnb parties. When you talked to Airbnb members, they took notes. If you offered them an idea during consultations at office hours, then by the next meeting they not only brought it to life, but also embodied two more new ideas that arose in their process. “They probably have a better outlook than any startup we've funded,” I wrote to Mike Arrington during the YC batch.

They are still the same. In the summer of 2018, Jessica, Brian, and I had dinner together. By this time, the company was ten years old. Brian wrote an entire page of notes on new ideas that could be put into Airbnb.

When we first met Brian, Joe and Nate, we didn't realize that Airbnb was on its last legs. After working for the company for a year and failing to grow, they agreed to give it one last chance. They went to Y Combinator, and if it didn't work, they would have given up.

Any normal person would have given up by now. They took out personal loans for the needs of the company. They had a folder with exhausted credit cards. Investors weren't very happy with this idea. One investor they met at the cafe left in the middle of the meeting. They thought he went to the toilet, but he never came back. “He didn't even finish his smoothie,” Brian said. And besides, at the end of 2008 there was a financial crisis. The stock market fell and continued to fall for another four months.

Why didn't they give up? This is a helpful question. People, like matter, reveal their nature in extreme conditions. One thing is clear: they did it not only for money. In terms of earnings, it was pretty lousy: a year of work, and all they had to show for it was a folder of filled credit cards. So why were they still working on this startup? Thanks to the experience they got as the first "landlords".

When they first attempted to rent out inflatable beds on their floor during a design conference, all they hoped for was make enough money to pay this month's rent. But something amazing happened: they liked that those first three guests stayed with them. And the guests liked it too. Both they and the guests did it because in a way they had to do it, and yet everyone had a great experience. Obviously, there was something new here: for landlords, a new way of earning money, which was literally under their noses, and for guests, a new way to travel, which in many ways was better than hotels.

It was because of this experience that the Airbnb parties did not give up. They knew they had discovered something. They saw a glimpse of the future and could not miss it.

They knew that as soon as people tried what is now called "airbnb" once, they would "get hooked" on this service forever, and also realize that this was the future. But only if they try, and they didn't. This was a problem during Y Combinator: how to trigger growth.

Airbnb's goal during YC was to achieve what we call a doshirak startup., which means getting enough money so that the company can pay the living expenses of the founders if they live on buckwheat or doshirak. Obviously, doshirak profitability is not the ultimate goal of any startup, but it is the most important threshold on the way, because this is where you fly on your own. This is the moment when you no longer need the "permission" of investors to continue to exist. For Airbnb parties, the profit margin was $ 4,000 per month: $ 3,500 for rent and $ 500 for food. They glued this target to the bathroom mirror in their apartment.

To grow in a startup like Airbnb, you need to focus on the most popular segment of the market. If you can start growing there, it will spread to others. When I asked Airbnb's agents where the most demand was, they found out by search terms: New York. So they focused on New York. They went there in person to visit landlords and help them make their ads more attractive. This required better quality photographs. So Joe and Brian rented a professional camera and photographed the landlords themselves.

This move did more than just improve their catalogs. The founders learned a lot about landlords. When they returned from their first trip to New York, I asked what they noticed about the landlords, what surprised them, and they said that the biggest surprise was how many landlords were in the same position they were in: they needed money to pay the rent. As a reminder, it was the worst recession in decades, and it hit New York first. It definitely reinforced the Airbnb's mission to feel like people needed them.

In late January 2009, about three weeks after starting Y Combinator, their efforts began to pay off and their metrics began to climb. But it was hard to say for sure if it was growth or just a random fluctuation. By February, it was clear that this was real growth. They made $ 460 in the first week of February, $ 897 in the second, and $ 1,428 in the third. That's all: they took off. On February 22nd, Brian sent me an email announcing they were profitable and giving me the numbers for the past three weeks.

“I suppose you know what you are counting on next week,” I replied.

Brian's answer consisted of seven words: "We are not going to slow down" ("We are not going to slow down").

If you want to help with translations of useful materials from the YC library, write in a personal, @jethacker cart or mail alexey.stacenko@gmail.com

Follow the YC Startup Library news in Russian in the telegram channel or on Facebook .

Useful materials

- A selection of 143 translations of Paul Graham's essays (from 184)

- 75 lectures in Russian from Y Combinator (out of 172)

- Y Combinator: Russian-speaking founders

- What startups Y Combinator is looking for in 2020

- Chat Y Combinator in Russian

- Public on Facebook YCombinator in Russian