Finding the tomb of an ancient king, full of gold artifacts, weapons and exquisite clothing, is the dream of any archaeologist. But looking for such objects is incredibly tedious, Dr. Gino Caspari would tell you.

Gino Caspari, an archaeological researcher for the Swiss National Science Foundation, studies the culture of the ancient Scythians and nomads who terrorized the populations of the Asian plains 3,000 years ago. In the tombs of the Scythian nobility, most of the fabulous wealth, stolen from their neighbors, is kept. From the moment the bodies of the leaders were buried, the graves became targets for robbers. According to Dr. Caspari's estimates, more than 90% of them have already been destroyed and ruined.

The scientist suspects that thousands of tombs are scattered across the Eurasian steppes stretching for millions of square kilometers. He spent hours mapping graves using Google Earth imagery in what is now Russia, Mongolia, and Xinjiang province in western China.

“Actually, it's a pretty boring and repetitive job, ” says Dr. Caspari. " And this is clearly not what a highly educated scientist should do."

Pablo Crespo, a graduate student of the Faculty of Economics at the City University of New York, managed to find a more optimal solution for the scientist's problems. He worked with artificial intelligence assessing the volatility of commodity markets. Pablo suggested to Dr. Caspari that a convolutional neural network could help him in the search for potential Scythian tombs - it could analyze satellite images just like a respected scientist.

Pablo and Gino were “colleagues” at International House (a worldwide network of 160 language schools and teacher training institutes in over 50 countries). They were united by a belief in the importance of the general availability of knowledge and academic collaboration. They also both loved heavy metal. Over a glass of beer, they launched a scientific partnership and opened a new page in the history of archaeological research.

convolutional neural network (CNN) is ideal for analyzing photographs and other images. CNN sees the image as a grid of pixels. The neural network, designed by Pablo Crespo, starts by assigning a rating to each pixel based on its color - how red, green, or blue it is. After evaluating each pixel according to many additional parameters, the network begins to analyze small groups of pixels, then larger ones, looking for matches with the data that it has been trained to detect.

Working in their spare time, the two researchers analyzed 1,212 satellite images over the network over a period of several months, searching for circular stone tombs. The tricky part was not to confuse them with other circular objects, such as piles of debris and irrigation ponds.

At first, they worked with images of about 2,000 square kilometers. They used three-quarters of the images to teach the network what a Scythian tomb looks like and to correct it when it missed the tomb or selected other objects as burial. The scientists left the rest of the images to check the system. As a result, the network correctly identified the tombs in 98% of cases.

According to Dr. Crespo, the network was not difficult to create. He deployed it in less than a month using Python at no extra cost. Unless, of course, you do not count the beer bought and drunk this month. Dr. Caspari hopes CNN will help archaeologists find new tombs so they can be protected from treasure hunters.

Convolutional neural networks help automate scientific tasks involving infinitely repetitive actions, which are usually blamed on graduate students. Artificial intelligence opens new windows to the past. Thus, the networks have learned to classify fragments of ceramics, detect sunken ships from sonar images, and find human bones sold on the black market on the Internet.

“With technology like this, Netflix is giving us movie recommendations, ” said Pablo Crespo, now a senior fellow at Etsy. - Why do not we use it for something like preservation of human history "?

Gabriele Gattilla and Francesca Anichini, archaeologists at the University of Pisa in Italy, are excavating an area of Roman monuments, which entails the analysis of thousands of broken pieces of pottery. In Roman culture, almost all types of utensils, including cooking utensils and amphorae used to transport goods across the Mediterranean, were made of clay. Therefore, the analysis of pottery is important for understanding the life of the ancient Romans.

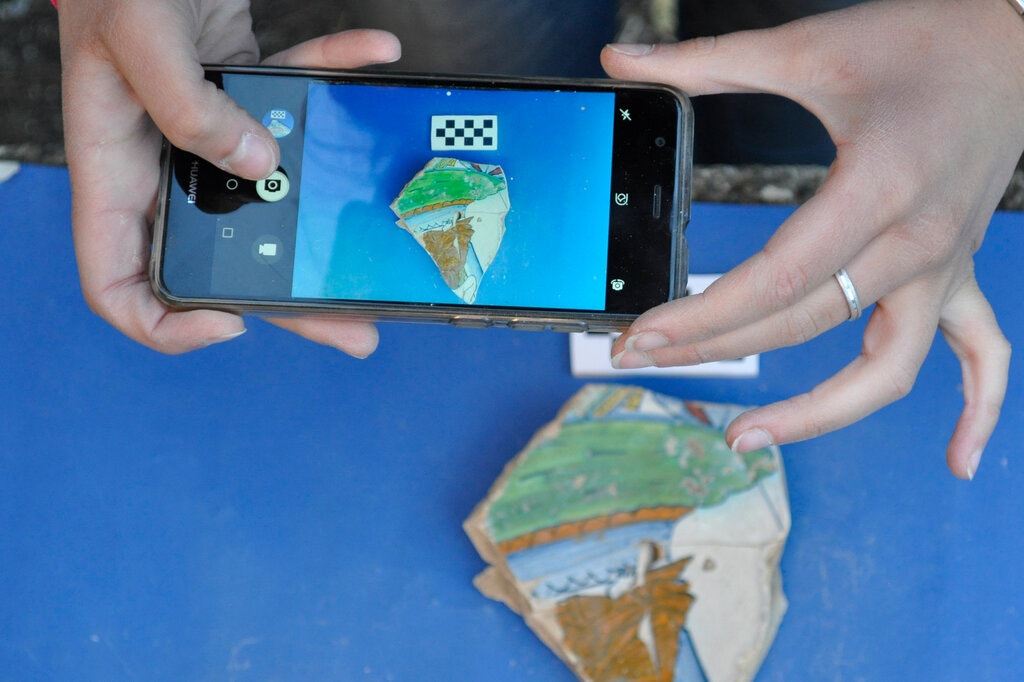

The challenge is to compare pottery shards with images in printed catalogs. Dr. Gattiglia and Dr. Anichini estimate that only 20% of their time is spent on excavations. The rest is spent on analyzing pottery - a job they don't get paid for.

“We have long dreamed of some kind of magical tool for identifying pottery in the excavation ,” said Dr. Gattiglia.

This dream has culminated in the ArchAIDE project, a digital solution that will allow archaeologists to photograph discovered pottery in the field and identify it using neural networks. The project, which has received funding from the Horizon 2020 project, now involves researchers from all over Europe, as well as a group of computer scientists from Tel Aviv University in Israel, who developed the neural network.

The project involved digitizing paper catalogs and training a neural network to recognize different types of ceramic vessels based on these images. The second network was trained to recognize the contours of the pottery shards. So far, ArchAIDE can only identify a few specific types of ceramics, but as the database grows, the capabilities of the neural network are expected to grow.

“I dream of a catalog of all types of ceramics, ” said Dr. Anichini. " But it seems like it's not a one-life job."

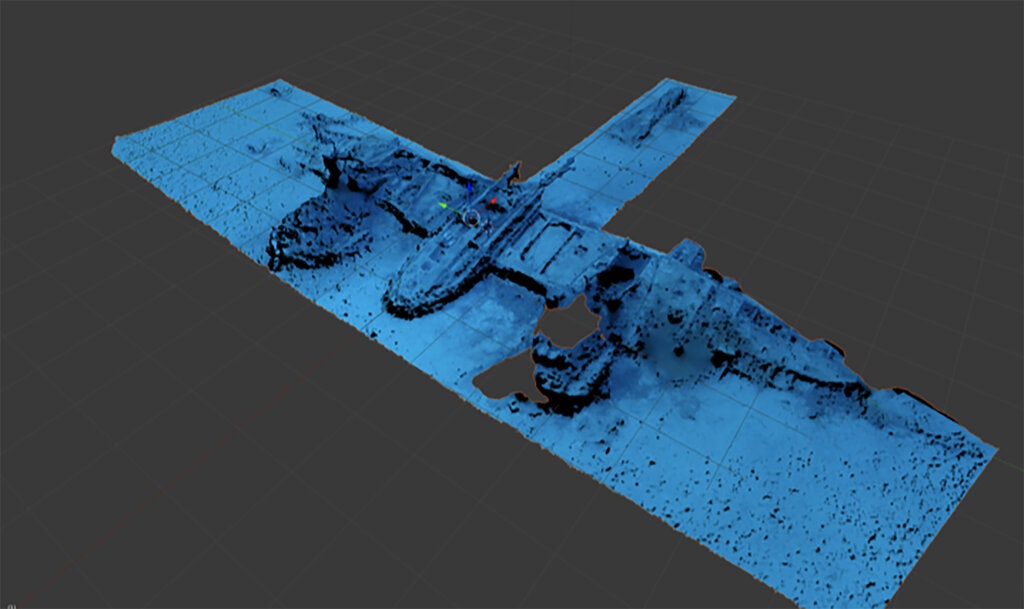

Saving time is one of the biggest benefits of neural networks. In underwater archeology, time is expensive, and explorer divers cannot spend too much time underwater without risking their health. Chris Clarke, an engineer at Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, California, solves both problems by using a robot to scan the seabed and then uses a neural network to process the images. In recent years, he has worked with Timmy Gambin, an archaeologist at the University of Malta, to study the Mediterranean seabed around the island of Malta.

The start was not easy: during one of the first "swims" the robot collided with the place of a shipwreck, and the scientists had to send a diver after it. After this excess, everything got better. In 2017, a neural network identified what turned out to be the wreckage of a World War II dive bomber. Dr. Clarke and Dr. Gambin are currently working on a different problem, but do not want to reveal details yet.

Sean Graham, professor of digital humanities at Carleton University in Ottawa, uses a neural network called Inception 3.0. CNN, developed by Google, helps people search through images on the Internet for advertisements for the purchase or sale of human bones. In the United States and many other countries, there are laws requiring that human bones in museum collections be returned to the descendants of the "owners" of the bones. But there are people who break this law. Dr. Graham said he even found videos on the internet of people digging graves to feed the black market.

He made some changes to the Inception 3.0 network so that it can recognize photographs of human bones. The system had already been trained to recognize objects in millions of images, but none of those objects were bones. Since then, he has trained his neural network on over 80,000 images of human bones. The scientist is now working with an organization called Internet Crime Control, which uses neural networks to track images associated with the illegal ivory trade and sex slavery.

Scientist Crespo and Caspari are convinced that the social sciences and humanities will only benefit from the introduction of IT. Their convolutional neural network is easy to use and available for modification according to research objectives. Ultimately, they say, scientific advances boil down to two things.

“New discoveries happen at the intersection of what has already been learned, ” says Gino Caspari. “From time to time, do not deny yourself a beer with a neighbor, ” concludes his colleague Dr. Crespo.