SPOTTING: The American company has information about my location.

There are 160 applications in my phone. I don't know what they are doing, but I decided to find out.

I had the feeling that these apps were spying on me. Of course, they don't wiretap me, but they constantly monitor where I am. That my every step is transmitted to someone: when I go to the grocery, drink or chat with friends.

I know that there are those who buy and sell this information. How do they track us and what do they want to do with our data?

To get to the bottom, I started an experiment in February. I installed a bunch of applications on my spare phone and then started carrying it with me everywhere.

Or almost everywhere. I left him at home when I was tested for COVID-19 in April.

Ease of abuse

The feeling of being watched grew stronger over the years, and I had reasons for it. This spring I was part of the NRK (Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation) team documenting how over 8,300 mobile phones were tracked while in hospitals or women's shelters.

For 35,000 NOK (€ 3,300 / $ 4,000), we got access to location data showing where tens of thousands of Norwegians traveled in 2019.

One of them was 31-year-old Karl Björn Bernhardsen from Stavanger. The information allowed us to easily identify him from the data, which, according to the data provider , has been anonymized.

When we called him, we were able to tell him where he was almost every day of 2019. Zoo. Job interview. In the hospital, where he stayed for several days as the father of his first child.

Then Karl told us that if it falls into the wrong hands, anyone can use this information.

Betrayal

We are often told that commercial tracking is not so bad: "It's only used for advertising." But there are many others interested in the digital footprint of our phones.

In a recent posting by Vice Motherboard, it was discovered that the U.S. military is buying location data and that the Muslim prayer app is sharing user location data with defense contractors.

"It looks like a betrayal," said the local head of the Council on American-Islamic Relations.

In 2018, the owner of a gated restaurant Kentucky Fried Chicken was arrested in a border town in Arizona. He is suspected of being involved in drug smuggling from Mexico through a tunnel under the US border.

TUNNEL: A 180-meter tunnel starting at the Mexican house and ending at the indoor KFC restaurant.

According to the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) , the crime was solved in part because the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) uses commercially distributed location data.

An article in the WSJ suggests that the business data was allegedly passed on to the ICE deportation department. US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has also acquired access to "global" location data .

There is a reason why NRK journalists are asked to think carefully before taking the phone to meet a confidential source. Authorities can access information about their location even without court permission.

If my location data falls into the wrong hands, it could affect other people as well. We constantly fear that it will be possible to identify who provided information in confidence.

I require access to my data

The company that supplied ICE with information about the fast food restaurant is called Venntel. According to the company's records, it is located in an industrial cluster in Virginia.

In the same area, you can find familiar names from the defense sector, for example, Lockheed Martin, the company that created the F-35, and the former employer of Edward Snowden, Booz Allen Hamilton. It is enough to make a 20-minute drive east and you will find yourself in Langley, Virginia, where the headquarters of the CIA is located.

DEFENSE CLUSTER: Venntel is registered in this building in the Virginia Industrial Cluster, USA.

On August 20, I requested a copy of all the information Venntel had on me. As a result of the 2018 GDPR, all Europeans are entitled to do so.

The next day, Venntel's legal department asked me for some of the addresses I had recently visited.

“After receiving this information, we will first check if the Advertiser ID you provided is in our database,” the email said.

Advertiser ID is what every smartphone has. This identifier is the key to tracking phone users across time and apps. Phone owners can restrict the ease of access to this identifier, however, few do it .

I have provided Venntel with the address of my office in the NRK building and my apartment in Oslo.

Sales data

Almost a month later, I received an interesting email attachment from Venntel. It contained information about where I had been 75406 times since February 15th. Suddenly I had the opportunity to track my every step - on a walk, in a bar, visiting my grandmother in southern Norway.

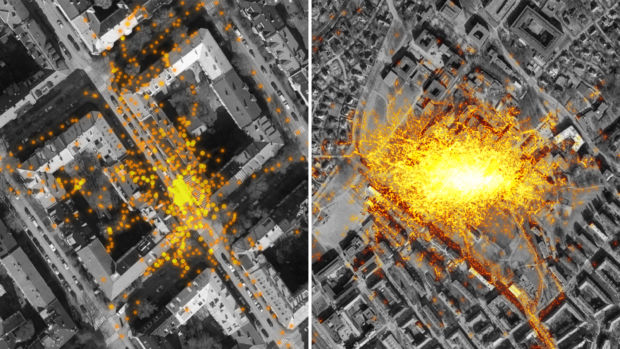

POINTS: The photo on the left shows the registration of my movements in the vicinity of my apartment. In the photo on the right you can see a map of the NRK office in Oslo's Marienlyst area. Over time, a huge number of registered locations have accumulated in these places.

There are no phone numbers or names in the data. However, almost anyone could easily figure out that these are my movements. A simple search on Google and the telephone directory would reveal that there is Martin Gundersen living in Sorgentfrigata in Oslo and working for NRK Marienlyst.

Venntel also notified me that it was sharing my information with its clients. Her clients use this information for purposes such as federal law enforcement and homeland security.

Who these customers are, Venntel declined to disclose.

A closely guarded secret

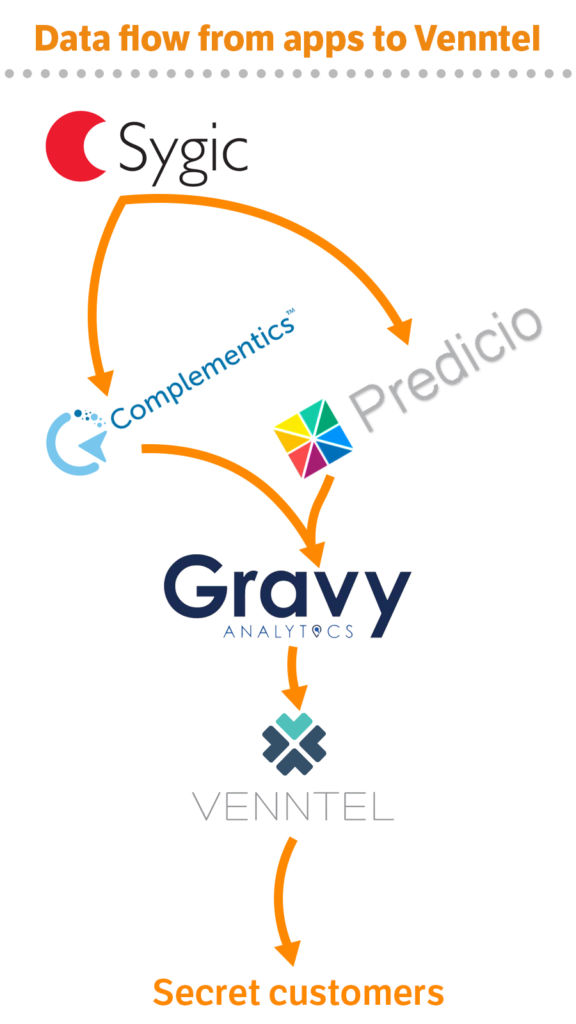

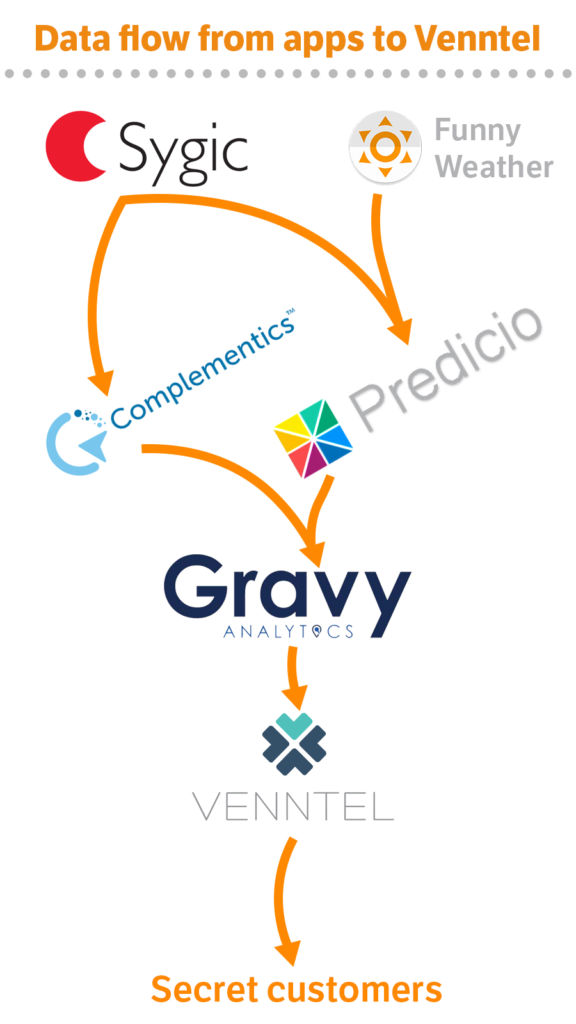

How could my location data end up with Venntel in the US? None of the apps I installed mentioned this company. Nowhere, not even in a confusing privacy policy that hardly anyone reads before clicking OK.

Venntel was able to inform me that it received my information from its parent company, Gravy Analytics, and that it only rarely knew about the applications that were associated with it.

Gravy Analytics is a marketing data broker. The company collects massive amounts of consumer data to improve its ad targeting. Gravy Analytics also claims to know nothing about the origin of most of the data. However, the response to the access request contained the names of two more new companies: Predicio (France) and Complementics (USA).

New access requests revealed that some of the location data eventually ended up in Venntel came from the Slovak app developer Sygic, which has 70 apps in its portfolio.

The developer's webpage claims that its most popular app has 200 million users.

On February 15th, I installed two Sygic navigation apps. Both asked me to agree to ad personalization terms.

If you are one of those people who hardly reads what they consent to, then you are not alone. In fact, very few people read the terms of use of the installed applications and services.

I clicked on "I agree". Since then, a binding agreement has been made between me and the application.

Violated privacy laws

It appears that when Gravy Analytics received the data, the agreement with Sygic was violated. Gravy Analytics states in its privacy policy that my personal information may be used in a set of services for partners and customers of the company. According to their own privacy policy, their goals include, among others, fraud detection, law enforcement and national security.

In other words, Gravy Analytics has shared my location data with its subsidiary, which provides these specific services.

Which brings us back to my agreement with Sygic on February 15th.

I consulted with three lawyers, Malgorzata Agnieszka Sindecka, Lee Baygrave and Arve Feyen; they are all privacy specialists. They believe that the ability to use my personal information for purposes for which I have not consented is a clear violation of the GDPR, as this law imposes strict restrictions and requirements on what can be done with personal information.

STRICT REQUIREMENTS: "If it turns out that partners may use personal information for purposes other than those for which you have agreed, then you will lose your privacy," says Sindetska.

This proliferation of functions is unacceptable. According to the associate professor of the Faculty of Law at the University of Bergen, Malgorzata Agnieszka Sindecka, such a practice undermines not only the principle of targeted restrictions, but also the principles of transparency and honesty defined in the GDPR.

Funny weather forecast with a gimmick

In addition, according to data files from Gravy Analytics and Venntel, the weather application Fu *** Weather also followed me. From the description, the app should present the weather forecast in a sarcastic, caustic manner. Who doesn't want to spice up their daily weather forecast with a bunch of foul language?

When installing the application this fall, I agreed that my data can be used for analytics and "monetization", i.e. funding the application.

The same three lawyers I consulted believe that this agreement is not GDPR-compliant because it is not clear from it what is meant by "monetization." In addition, the collection of analytics is not consistent with all Venntel business practices.

POOR WEATHER CONDITIONS: Funny Weather does not recommend sticking your head out of the window to check the weather as it can ruin your mood.

Funny Weather developer Lavius Fras doesn't work for any big company. He said he did not know Venntel, but said he was not hiding the application's business model.

“The fact that I partner with companies that use some of the data the app has access to to make money is not confidential,” Lavius Fras wrote to me in an email.

Frase acknowledges that the appendix could have been more clear about the implications of being able to "monetize". He intends to make changes to the privacy policy for this, but continues to maintain that users have been duly informed.

Inability to trace

How the data from Funny Weather got to Venntel remains a mystery, but it is likely that it went through the French company Predicio, listed as an intermediary in the app's privacy policy.

What other applications Venntel can receive data from is a closely guarded secret. Even the owners of mobile apps don't know what they were involved in.

“We don't know Venntel,” said Zuzana Kasanova from Sygic when I asked how my data came to be with the company.

Kasanova stated that my consent was legally obtained in accordance with the GDPR, and that her company's partners under the contract are obliged to use my data only for marketing purposes.

“Based on the information you have provided, it is unclear that the source of the data Venntel received about you was Sygic GPS Navigation. If it turns out that this is so, then this is a violation of the agreements we have concluded with our partners. "

NRK's technical analysis shows that the data from Sygic ended up in Venntel. For example, the ID used by Complementics for the Sygic data is also present in the Venntel data.

Kasanova did not answer the question of what implications this will entail for Sygic's partnerships with Predicio or Complementics.

A system built on illegality

With the introduction of the 2018 GDPR, privacy advocates have achieved an important victory. The pan-European law was intended to provide stricter supervision of companies that trade in user data. However, parts of the digital advertising industry have not changed much.

“Companies are trying to stick with old practices and disguise them as something different, but at the core they have remained the same,” says David Martin from Brussels.

He leads the Digital Rights Division at BEUC, the umbrella group of European consumer organizations. According to Martin, "Parts of the digital advertising system are based on an almost systematic violation of the GDPR."

He shares the opinion of most privacy advocates: GDPR is excellent in theory, but in practice it has serious flaws.

David Martin, BEUC.

Austrian privacy activist and researcher Wolfi Krystl has researched how companies use our data for many years. He recently helped the Norwegian Consumer Council with the "Out of Control" report documenting many potential privacy violations in the app ecosystem.

“In most cases, it is difficult or even impossible to track the movement of personal data between applications, data brokers and their clients,” he says.

According to Krystle, the EU data protection authorities are either unable or unwilling to end GDPR violations.

“We will not see any changes without imposing huge fines and bans on data processing. EU member states and the EU Commission must act, ”he says.

The question is whether anyone would like to hear it. And also in how easy it will be to prosecute for alleged violations. Arve Føyen, partner at law firm Føyen Torkildsen, believes it is difficult to punish companies like Venntel, since they have no offices in Europe.

“I'm afraid this creates an illusory impression of the rules being applied, but in practice it is simply impossible to take any legal action,” explains Feyen.

Digital photo album

It has been several months since I brought my spare phone to the Ullevålseter sports hotel, a popular place in the Nordmark forest for coffee and waffles.

On my screen, I see the dots winding along the forest paths. Many clusters where I rested; where I walked quickly, they are scattered less often.

SNACK: I came from the right path. Then I paused in the courtyard, a little confused, and then I found a wooden bench on the right. Overall, this photo captures 36 minutes of Sunday, August 9th.

It was a hot Sunday in late summer. Horseflies swarmed, especially over the swampy areas.

We usually forget most of the places we have been and what we did there. However, a couple of hints are enough for the memories to return. Recovering my steps that summer Sunday was like flipping through an old album, each page of which has its own story.

But the funny thing is that this data, my movements, is stored by someone else.

It is very unpleasant to follow your own steps, even if they are not associated with any love affairs, secret meetings or delicate health problems.

Most of us have moments in our lives that we would not want to share. Even with their loved ones, bosses or the state.

I was able to recover the data flow from mobile apps to Venntel, but there were still a lot of unanswered questions. Which Venntel customers received information about me? Were these companies in the defense sector, intelligence or the FBI?

Answers that are hard to get

Gravy Analytics did not respond to our multiple requests. Her subsidiary Venntel declined to be interviewed by phone or email.

In a short statement, Venntel states that my phone movements were not broadcast by ICE or CBP. She also wrote that she has nothing to do with the application vendors Sygic or Lavius Fras. (NRK has never stated that they have a direct link, but has documented that the company obtains information from these applications through third parties.)

"We will not leave further comments about our business relationships or interpretation of legislation," Venntel wrote.

In a statement to NRK, the US Border Protection (CBP) said that it has limited access to commercially available data and that it is being used in accordance with relevant rules and regulations. (The full text of the statement can be found at the end of the article).

CBP Press Officer Jason Givens did not respond to follow-up questions about what restrictions are placed on CBPs when it comes to retrieving data on European citizens or phones located outside US borders.

The FBI and ICE also have agreements with Venntel, but they did not respond to questions about the company's ability to track Europeans inside and outside Europe.

When Predicio responded to the access request on August 11, the company did not mention Venntel data transfers in February-July. (The Funny Weather app was installed on Aug 10.) Predicio did not respond to my repeated requests for interviews.

Complementics co-founder Walter Harrison stated that my data was only used for marketing analytics. Harrison did not want to participate in the interview and did not respond to questions about the company's relationship with Gravy Analytics. When the Vice Motherboard asked Harrison about Gravy Analytics, he said that the company's contractual partner "cannot directly or indirectly share any data obtained from Complementics with any US intelligence, immigration or law enforcement agency."

: , , . , . Venntel ( , , , ), Gravy Analytics ( , , , ), Sygic ( , ), Predicio ( , ), og Complementics ( , , ). .

« — . , . , , . , , „ “ 1974 , , , , . , ».

ICE

« (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, ICE) , . Venntel : FPDS. GDPR ICE Venntel».

CBP

«- (U.S. Customs and Border Protection, CBP) , . , , CBP .

CBP , , , . , CBP . CBP, , CBP , ».

Servers for rent for any purpose are just about virtual servers from our company.

For a long time we have been using exclusively fast server drives from Intel and do not save on hardware - only branded equipment and the most modern solutions on the market for providing services.