In 1881, Victor Hugo and his grandchildren saw an incredible car in the hotel. Several wires with headphones came out of the wall: putting them on, the writer heard singing. I changed my headphones - and moved to the Comedie-Française, and then to the Opera-Comique. “The children were fascinated, and so was I,” the classic of French literature described his feelings.

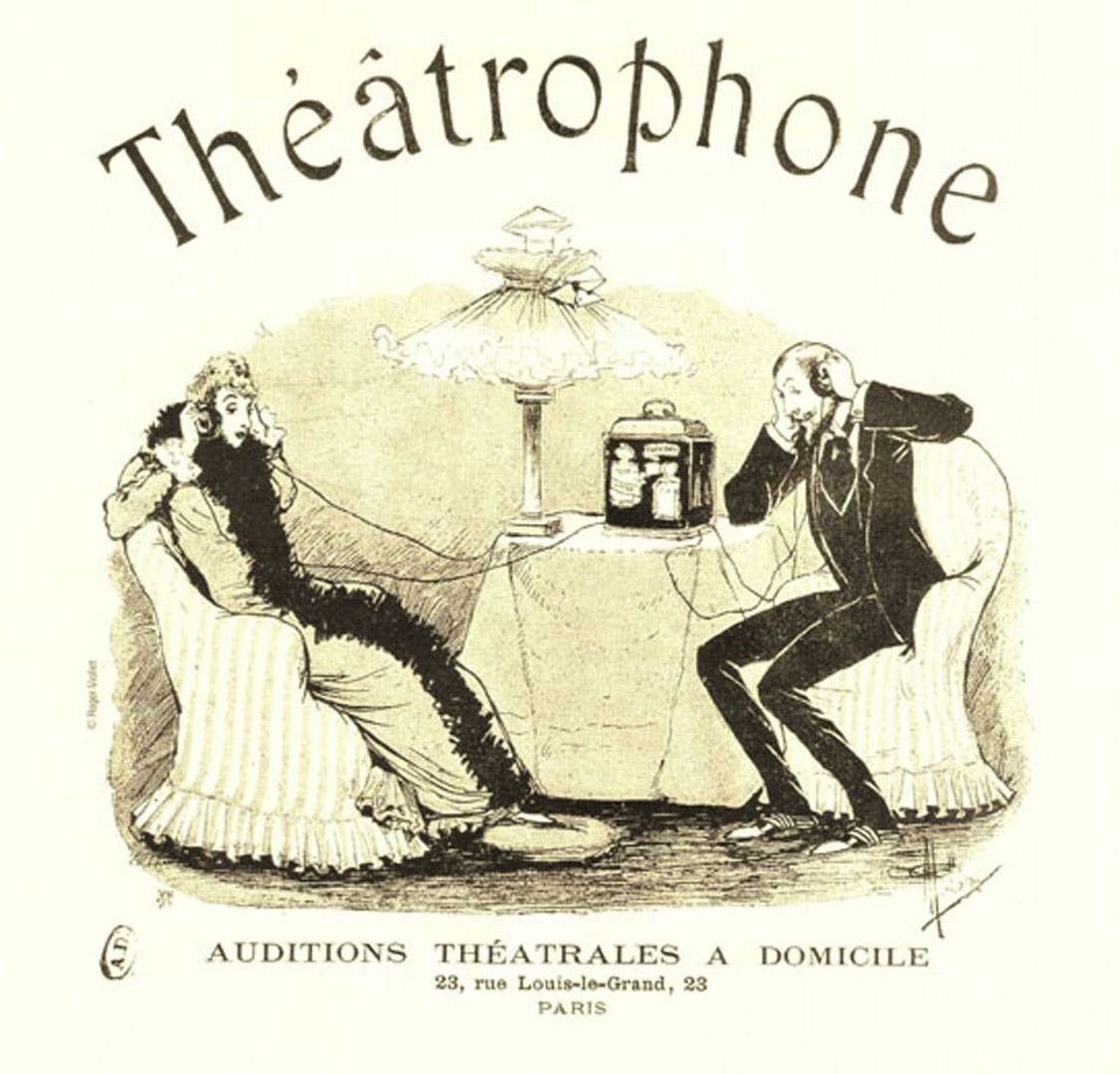

This happened even before the era of radio, just at the time of uncertainty, beloved by steampunk authors, when all technologies were just developing, and everything was possible. Then people thought to hold a telephone in theaters, operas and churches to listen to live performances and sermons. In France the system was called "Theatrophone", and in Great Britain - "Electrophone".

American Alexander Graham Bell invented the first ever working telephone in 1876. He was not the only one who worked on this technology, and from the very beginning engineers wondered how it could be used. During the first public demonstration of the invention, Bell was transmitting music over the wire, not a human voice. However, innovations in this area came from Europe.

The French were the first

Frenchman Clément Ader, another communications innovator, was the first to figure out how to let viewers listen to theater performances over the phone. In 1881, he put the idea into practice at the International Electrical Exhibition in Paris. Visitors could listen to live performances at the Comédie-Française and the Paris Opera, two kilometers from the exhibition.

It worked like this: Ader lined up 80 telephone microphones in front of theater stages to receive live sound. The signal was transmitted over the early telephone network to the headphones in the pavilion at the exhibition. The transmission was poorly amplified, but at that time it turned out to be an innovative idea.

Ader had his own telephone company and a patent for telephones, including a specially designed ten-rod carbon microphone. His best idea was stereo sound: the right earpiece conveyed what was happening on the stage on the right, the left one - what was happening on the left. This enthralled the audience, who felt the actors literally move across the stage. Let us recall that this took place in the 80s of the XIX century.

According to the physicist and lobbyist for electricity, Theodore du Monsel, the new technology has attracted many art enthusiasts to the exhibition.“Every evening, when the Opera was performing, we lined up to audition, and this fashion continued until the end of the exhibition. <...> Almost all conscientious listeners were delighted and claimed that they heard better than at the Opera. Which is easy to understand when you consider that the transmitters were placed between the actors and the orchestra. The latter was to some extent sacrificed to the actors, whose words could be heard wonderfully . "

Listeners at the 1881 World's Fair

After the exhibition, the system was dismantled, but not forgotten. In 1884, King Luis I of Portugal was unable to personally attend the San Carlo opera in Naples due to family mourning. Then the Edison Gower-Bell company, which was engaged in telephony in Europe, organized an audition of the performance for the monarch by telephone at the Ajuda Palace in Lisbon. The directors of the company were awarded the Military Order of Christ for his services. And the next year Opera began selling theater subscriptions itself.

"Theatrophone" walked across Europe. Ten years after Ader's demonstration, the Compagnie du Théâtrophone appeared in Paris. They launched for the 1889 World's Fair. The company has installed theater devices in hotels, cafes and clubs. The machines were connected to the opera, listening to it cost 50 centimes for 10 minutes. Moreover, any telephone owner in Paris could activate the service for the same price.

During the World's Fair during the daytime, theatrophones broadcast a mechanical piano concert, and their owners earned huge sums. The quality of the music was not impressive; but the new and incredible concept attracted customers.

A big fan of Teatrophone was the writer Marcel Proust. As you know, poor health prevented him from leaving the house, so the new invention was a salvation. In 1911, the writer signed up for the service and became a propagandist for telephone broadcasts, although he was dissatisfied with the quality of the connection.

Interestingly, Italians and Hungarians launched their own versions of the system, but used them to broadcast news to subscribers, not just entertainment.

Great Britain enters the race

Even before the new century, the theatrophone crossed the English Channel. Although the British will probably deny what they have done for their sworn allies, the fact is the fact: the British H.S.J.Booth founded the Electophone company only in 1894, his network began operating in London since 1895.

The system was built on a similar principle: for a fee, clients received access to broadcasts over the telephone network. However, the range of possible broadcasts was wider than that of Teatrophone: musical concerts, theatrical performances, scientific lectures and church services. Live streaming is the first time in the homes of Britons who can afford it: the then 5 pounds a year is equivalent to 120 modern pounds.

Covent Garden and the Adelphi Theater were connected to Electrophone in a scheme similar to Teatrophone. The microphones were hidden behind a ramp in front of the stage. For church services, the receivers were placed in counterfeit wooden Bibles. The Electrophone company paid for the installation of equipment in the theater and shared the profits with it, the National Telephone Company, and later the post office, paid for the maintenance of telephone lines.

The soldiers in the hospital, returning from the front, listen to the electrophone. The year 1917

seemed extremely profitable for the Electrophone Theaters, since the compact technology did not interfere with the performance and did not reduce the audience. On the contrary, those who listened to the performance on the phone, then more willingly came to look at the actors.

Those who could not afford the subscription still had the opportunity to enjoy the new technology. For this, machines with slots for coins were installed in hotels, squares and at exhibitions. Thanks to them, people could listen to fragments of concerts and performances. The listening salon was opened at the headquarters of Electrophone on Gerrard Street.

In the Salon on Gerrard Street

In May 1899, Queen Victoria first used an electrophone. The royal lady heard the performance of the boys' choir from the military and naval schools. The choir performed “God save the queen” for her. Then, along with the guests, she listened to a concert at St. James's Hall. The success of the newfangled technology was reported by The Electrician.

"Electrophone" did not work with stereo sound: this innovation remained in continental Europe. Which, however, did not diminish the enthusiasm. Journalists for The Musical Standard described that they heard the theater audience “rustle like leaves”. The monophonic sound did not spoil the presence effect. The listener seemed to be in the same hall and noticed both the mistakes of the actors and their triumphs.

Another important difference from Teatrophone was the way people listened to the broadcasts. For these purposes, "Electrophone" supplied special headphones with an arc, remotely similar to theatrical binoculars. By modern standards, it is a bulky structure with which you need to sit still. Again the French trace: the technology was influenced by a patent in 1891 by the French engineer Ernest Mercadier, who invented a similar accessory.

Nevertheless, there were those willing. At its peak, theatrical broadcast services were used by 2,000 subscribers. It was a rise before a fall. In 1920, radio began to spread as a common technology for transmitting data. In 1922, a group of leading manufacturers of radio receivers formed the BBC: British Broadcasting Company.

The director of Electrophone rashly told The Times in 1923 that "it will be a long time before wireless broadcasting of entertainment and church services reaches the perfection now available to the electrophone." Just two years later, the same newspaper wrote that Electrophone had lost most of its subscribers and profits, so its license was revoked and the service would stop broadcasting.

A similar system was launched in 1903 in Bournemouth, but it attracted 62 customers and closed in 1938 when only two subscribers remained. "Teatrophone" worked until 1932.

Now, in the era of ubiquitous Wi-Fi, mobile Internet, Netflix and YouTube, it's hard to imagine a world before massive broadcasts. When listening to another podcast or watching a TV series, remember that you are following a tradition that began as early as the people of the Victorian era.