For nearly a hundred years in a row, anonymous group members have written books expressing pure mathematical thoughts.

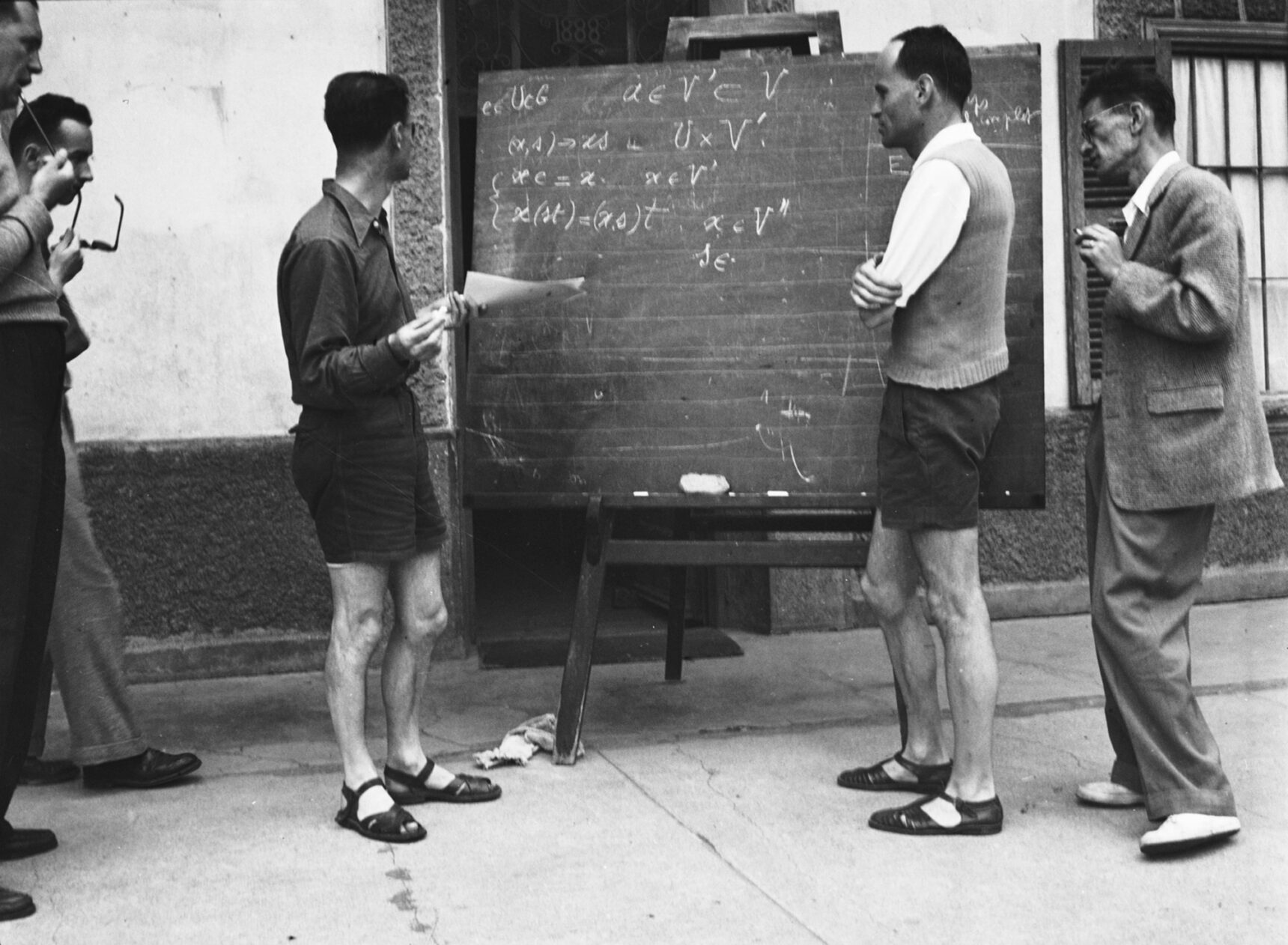

Some of the founders of the group are Henri Cartan (standing on the left), André Weil (standing second from the right) and Scholem Mandelbroit (sitting on the right). Antoine Chambert-Loire received an

invitation to talk with members of one of the oldest secret mathematical societies by phone. “I was told that the Bourbaki would like to meet with me to discuss possible joint work,” he said. Chambert-Loire accepted the invitation, and he spent one week in September 2001 reading aloud mathematical texts for seven hours a day, and discussing them with members of the group, whose identities are unknown to the rest of the world.

He was not officially invited to join the group, but on the last day of his stay he was given a long-term assignment to complete the manuscript the group had been working on since 1975. When Chambert-Loire later received the report of the meeting, he noticed that he was marked as a "membrifié", that is, a member of the group. Since then, he has helped develop an almost Sisyphean mathematical tradition that began before World War II.

The group is known as Nikola Bourbaki and is usually referred to simply as “Bourbaki”. This is a collective pseudonym, the surname of which was borrowed from a real French general of the 19th century, who, however, had nothing to do with mathematics. Why such a name was chosen is unclear, although it may be due to the rally organized by the founders of the group when they were still students at the École normale supérieure (ENS) in Paris.

“They had a tradition of playing pranks on freshmen. One of these pranks was to convince them that General Bourbaki should come to school to give some incomprehensible lecture on mathematics, ”said Chambert-Loire, mathematician from the University of Paris, acting representative of the group, and the only known members.

Nicola Bourbaki's group was founded in 1934 by a small handful of recent ENS alumni. Many of them were the best mathematicians of their generation. After carefully studying this area, they discovered a problem. What exactly this problem was is known only from rumors.

According to one version, Nicola Bourbaki was a response to the generation of mathematicians lost in the First World War. The founders of the group wanted to figure out how to preserve the mathematical knowledge that still remained in Europe.

“There is a story that the government did not have a special account of young French mathematicians, and many of them went to the First World War, where they died,” said Sebastian Guezel of the University of Rennes. He is most likely not associated with the group, but, like many mathematicians, he is aware of its activities.

A more prosaic and believable version of the appearance is that the members of the group were dissatisfied with the quality of the existing textbooks and wanted to create something better. “I think it all started with this particular challenge,” Chambert-Loire said.

One of the mathematics textbooks authored by Nicola Bourbaki, entitled "Foundations of Mathematics: Lie Groups and Algebras"

Whatever their motivation, the founders of the group began to write books. However, instead of textbooks, they ended up with something new: individual books describing advanced mathematical concepts without reference to external sources.

Bourbaki's first text was to describe differential geometry. This coincided with the tastes of some of the early members of the group - luminaries such as Henri Cartan and André Weil. However, the project expanded rapidly because it is difficult to explain one mathematical idea without involving many others.

“They realized that if they wanted to keep things clean, they needed to take ideas from other areas. Therefore, the Bourbaki project grew and grew, becoming just huge, ”Guezel said.

One of the distinctive features of Bourbaki was the style of the texts: strict, formal, reduced to pure logic. In books, mathematical theorems were formulated from the very beginning, without any omissions. Such thoroughness is unusual for mathematicians.

“Basically, Bourbaki has no passes,” Guezel said. "They're super accurate."

But this accuracy is not in vain - the books of Nikola Bourbaki are very difficult to read. They do not offer explanations for the origins of concepts, letting ideas speak for themselves.

“No comment on what's going on there or why,” Chambert-Loire said. "Things are postulated and proven, nothing more."

Nicola Bourbaki combined a distinctive writing style with a distinctive book writing style. After a member has drafted the recording, the group meets live, reads it aloud and offers comments. These steps are then repeated until everyone agrees that the text is ready to go. This process can take a decade or more.

Nicola Bourbaki remains a secret society, emphasizing the collective nature of the work, although there are no tough measures to preserve the anonymity of members

The persistence in maintaining anonymity stems precisely from the concentration on teamwork. The group keeps a secret of its composition, emphasizing the idea that books are pure expressions of mathematics at its core, and not the opinions of individual subjects. Such an ethic seems to be incompatible with the modern culture of mathematics.

“It's hard to imagine a group of young scientists today, people who have no permanent job for life, devote a huge amount of time to something for which they will not receive recognition,” said Lillian Pearce of Duke University. "This group is built on altruism."

Nicola Bourbaki's group quickly began to influence mathematics. Some of the first books published in the 1940s and 1950s introduced a new vocabulary that is now the standard - for example, terms such as injection, surjection, and bijection are used to describe relationships between sets.

This was the first of two major periods of Bourbaki's special influence on mathematics. The second began in the 1970s, when the group published several books on Lie groups and Lie algebras, which are "widely regarded as a masterpiece," Schambert-Loire said.

The members of Nicola Bourbaki value teamwork, discuss works together, speaking them out loud, and publish texts only after everyone has agreed.

Today the influence of the group's books has faded. They are better known for their "Bourbaki seminars", lectures on the most important modern mathematical results, held in Paris. When Bourbaki invited Pierce to give one of these lectures in 2017, she knew it would take a long time to prepare. But on the other hand, due to the status of these seminars in her field of study, "such an invitation is not refused."

And even organizing and attending public lectures, members of Nikola Bourbaki do not reveal themselves. Pierce recalls going to Paris to dine with "a few people who were clearly part of the community, but following the spirit of the idea, I did not try to hear their names."

Today, anonymity is maintained solely "for fun," Pearce said. “They are not taking harsh measures to keep secrets,” she said.

Although their seminars are now more influential than their books, the Bourbaki group - which includes about 10 people - still publishes tests that align with their founding principles. Chambert-Loire's time in the group is coming to an end, as he is already 49 years old, and traditionally people leave the group when he reaches 50.

Although he prepares to leave the group, the project that was entrusted to him after his first week of work is not yet finished. “For 15 years I have patiently recorded it in LaTeX, made corrections, and year after year we read it all out loud,” he said.

It can easily take fifty years from start to completion. This is a long time by modern publishing standards - often the work ends up online at the draft stage. However, it may not be that long for a product that is meant to last forever.