Countries around the world are promising to plant billions of trees in order to grow new forests. However, new research demonstrates that the potential for atmospheric carbon sequestration and climate change impacts in naturally regenerating forests is much greater than previously thought.

When Susan Cook-Patton was a postdoctoral fellow on reforestation at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center in Maryland seven years ago, she said she helped plant 20,000 trees in the Chesapeake Bay . This was a very valuable lesson. “The trees that didn’t grow the best were mostly trees,” she recalls. “They sprouted naturally on the ground that we prepared for planting. Lots of trees appeared here and there. It became a good reminder that nature knows what it is doing. "

What works in the Chesapeake Bay probably works in many other places, says Cook-Patton, now with the environmental charity The Nature Conservancy. Sometimes we just need to give nature a place to grow naturally there again. Her conclusion is from a new global study that the potential for natural growth of forests to sequester carbon from the atmosphere and influence climate change has been seriously underestimated.

Nowadays, forest planting is at the height of fashion. In Davos, this year's World Economic Forum called for the planting of a trillion trees. One of the US government's responses to climate issues was a pledge last month to plant nearly a billion (855 million) trees in 1.1 million hectares through commercial and non-profit organizations such as American Forests.

The European Union this year has promised to plant 3 billion trees as part of the Green Deal initiative. Under the 2011 Bonn Agreement and the 2015 Paris Agreement, there are already targets to restore more than 344 million hectares of forests, mainly through planting. This is slightly more than the area of India, and about a quarter of a trillion trees can grow in such an area.

Tree planting is widely regarded as the “natural solution” to climate change, a way to manage climate change over the next three decades, as the world works to achieve a carbon-free economy. However, some people object to this.

Nobody is against trees. However, some critics argue that aggressive pursuit of landing targets will only be a cover. Hundreds of millions of hectares of land will be occupied by fast-growing and often uncharacteristic commercial monocultural plantings: acacias, eucalyptus and pines. Others ask: why plant trees at all. If you can just leave the land for the nearby forests to sow and reclaim it? Nature herself knows what needs to grow, and she does it best.

A new study from Cook-Patton and her co-authors from 17 scientific and environmental organizations, published in the journal Nature, says estimates of the rate of carbon accumulation by natural re-growth of forests, confirmed last year by the United Nations interstate committee on climate change, averaged 32% lower than necessary. In the case of tropical forests, this figure goes up to 53%.

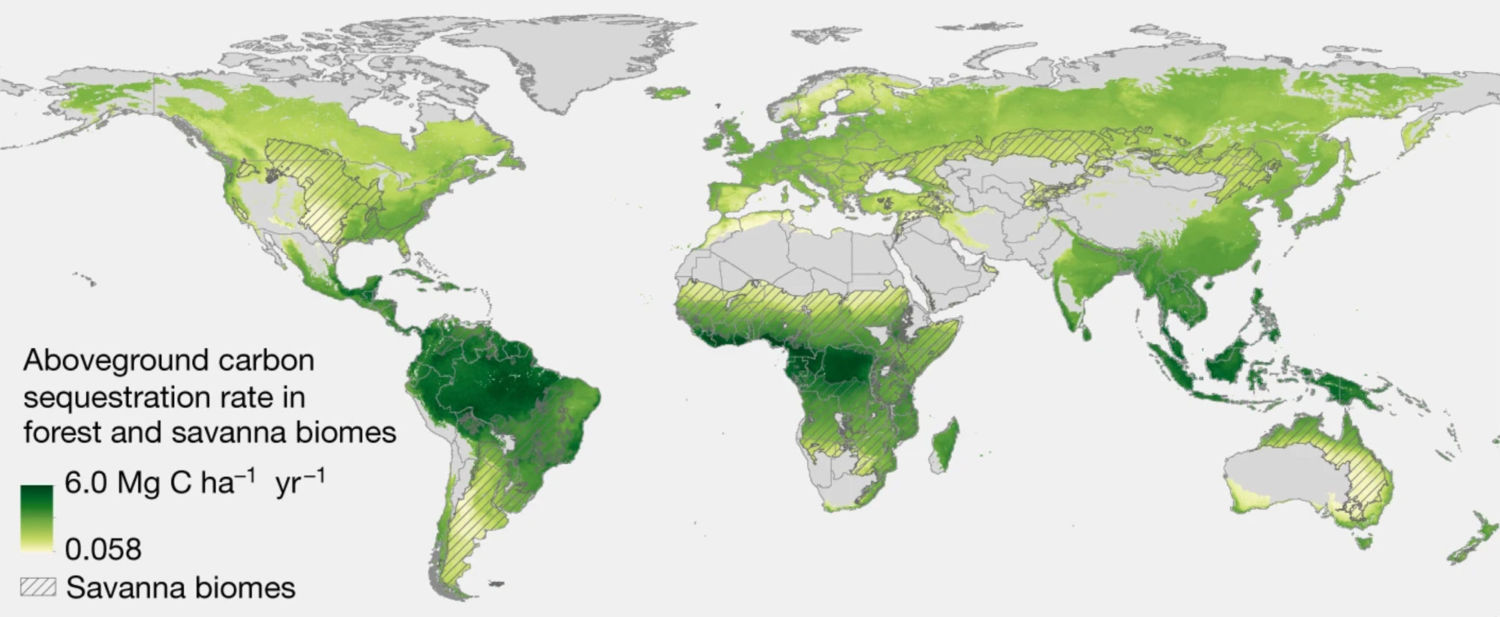

This study is the most detailed effort ever to map out where forests could grow naturally and to assess their carbon storage potential. “We looked at nearly 11,000 carbon sequestration measurements from regrowth forests from 250 studies around the world,” said Cook-Patton.

New plants sprout amid burnt Amazon trees in the Brazilian state of Para

She found that the rate of carbon accumulation in different cases can differ a hundredfold, depending on climate, soil, altitude and landscape. This is a much wider spread than previously thought possible. “Even within the same country, the difference could be huge.” But on average, natural regeneration was not only more varied, but also capable of absorbing more carbon, at a faster rate and in a safer way than plantations.

Cook-Patton agrees that climate change will pick up steam over the coming decades and the rate at which carbon builds up will change. But if some forests grow more slowly or even die out, others are likely to grow faster due to the effect of fertilizing the soil or increasing carbon in the air - this effect is sometimes called global greening.

The study counted 670 billion hectares that could be left for tree re-growth. This is not counting land for plowing or construction, and existing valuable ecosystems such as meadows and northern areas, where the warming effects of the forest canopy will outweigh the cooling effect of carbon sequestration from the air.

By combining cartographic data and carbon stock numbers, Cook-Patton estimates that natural forest growth by 2050 will be able to bind 73 billion tonnes of carbon in its biomass and soil. This is the equivalent of seven years of current industrial emissions - in her words, "the most powerful natural solution to the climate problem."

Cook-Patton said the study's local carbon stock estimates fill an important data gap. Many countries looking to grow forests to store carbon have collected data on what can be achieved by planting trees, but have not calculated equivalent data for natural forest regeneration. “I get e-mails all the time asking how much carbon can be captured by natural growth projects,” she says. - I had to answer that it depends a lot on what. But now we have data that will allow people to estimate what will happen if you just put up a fence and let the forest grow back on its own. "

Carbon accumulation rate in tonnes per hectare per year in naturally regenerating forests and savannas

New local estimates also allow comparisons of the potentials of natural recovery and planting. “I think that planting can also take place - for example, where the soil is damaged and the trees do not grow,” she said. "But I think natural forest regeneration is seriously underestimated."

What's good about the natural growth of forests - most often it does not require any action from a person. Nature constantly regenerates forests in parts - sometimes along the edges of fields, or in abandoned pastures, in bushes, in places of former felling, or where the forest is in decline.

But since this does not require any political initiative, investment or observation, data on this issue is sorely lacking. A satellite like Landsat, for example, does a good job of finding places where forests are being destroyed, because it happens suddenly and is clearly visible. However, their subsequent recovery is slower, harder to notice, and rarely studied. The headline statistics on global forest cover loss tend to ignore these developments.

In researchA rare type Philip Curtsey of the University of Arkansas recently tried to get around this problem by developing a model that predicts, from satellite images, the cause of the loss of forest cover - and therefore the potential for reforestation. He found that only a quarter of the forest that had disappeared was forever occupied by human activities such as building buildings, infrastructure or farming. The remaining three quarters are forest fires, shift farming, temporary grazing or logging. At least they have the potential for natural recovery.

Another study, published this year, shows that such restoration is taking place on a large scale and quickly, even in areas as characteristic of deforestation as the Amazon. When Yunxia Wang of the University of Leeds in England analyzed data recently published by Brazil on the Amazon, she found that 72% of the forests that farmers burn to create new pastures are not pristine forest as previously thought, but recently restored. The territory was cleared of forest, turned into a pasture for livestock, and then left. The forest returned there so quickly that it had to be cleaned again after six years. This rapid recovery has caused confusion, which has often led the area to be classified as a site where the old forest is dying out.

Wang noted that if Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro wanted to keep the promise of his predecessor Dilma Rousseff at the 2015 Paris Climate Summit to restore 12 million hectares of forests by 2030, he would not need to plant forests at all. He could simply allow them to recover without clearing new territories from the forest.

Another giant forested area, the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, is already on its way, slowly recovering from a century of clean-ups to free up coffee and grazing grounds. The government has adopted a pact for the restoration of the Atlantic forest, which provides subsidies to farmers to plant new forests. Often trees are used for this, intended for obtaining paper. But Camila Resende of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro says much of the forest is being restored not by planting, but by natural, " spontaneous " methods. Remnants of the forest colonize abandoned farms. She estimates that since 1996, about 2.7 million hectares of Atlantic forest have been restored in this way - this is about a tenth of the entire massif.

Something similar is happening in Europe, where the forest area has recovered by 43% , which is often due to the natural occupation of territories. For example, in Italy, the area of forest cover has increased by one million hectares . In the former socialist countries in the Carpathians, 16% of farm lands were abandoned in the 1990s . Most of them are again occupied by the famous beech forests. In Russia, the former arable land with an area of two Spain was again occupied by forests. Irina Kurganova , a leading researcher at the Russian Academy of Sciences, calls this plow retreat "the largest and most dramatic change in land use practices in the 20th century in the Northern Hemisphere."

The United States is also seeing forest regeneration as nearly one-fifth of arable land has been abandoned over the past 30 years. “The entire eastern United States was deforested 200 years ago,” says Karen Hall of the University of California, Santa Cruz. "Most of the forest has returned without active tree planting." Over the past three decades, regenerating forests have linked about 11% of the country's greenhouse gas emissions, according to the US Forest Service.

A worker plants young Sitka fir trees as part of a reforestation project in Dodington, England, in 2018

The main concerns are related to the fact that the land intended for planting trees will be taken away from the forest, which could grow on them naturally. As a result, there will be fewer wild animals living in such a forest, it will not be so convenient for humans, and it may not bind much carbon.

Environmentalists have often dismissed the environmental benefits of natural reforestation - the so-called. "Secondary forest". It is believed that such restoration is incomplete, wild animals rarely settle in it, and it is subject to repeated cleaning. Because of this, many people prefer manual tree planting that mimics a natural forest.

Thomas Crowfer, co-author of last year's highly publicized studycalling for "global restoration" of millions of trees to absorb carbon dioxide, emphasizes that while nature can handle it in some places, "people need to help it by distributing seeds and saplings."

However, these views are now being revised. J. Leighton Reid, director of the Restoration Ecology Lab at Virginia Institute of Technology, recently raised concerns about bias in studies comparing natural forest regeneration to planting. However, he said, "Natural growth is an excellent recovery strategy for many landscapes, but active planting of native plants will still be the best option in areas where the soil is most severely affected or where weeds are prevalent."

Others argue that in most cases, natural regeneration of secondary forest works better than planting. In her book Secondary Growth, Robin Chazdon, a forest ecologist formerly at the University of Connecticut, says that secondary forests are “still misunderstood, understudied, and underestimated. But these are young self-organizing forest ecosystems in the process of development. "

She agrees that these systems are not complete forests. But they usually recover “surprisingly quickly”. Recent research shows that self-regenerating rainforests replace 80% of biological diversity in 20 years, and often 100% in 50 years. The result seems to be better than that of people trying to plant tropical ecosystems.

A review of over 100 tropical rainforest restoration projects by Renato Cruzeile of the International Institute for Sustainable Development of Rio de Janeiro, with Chazdon as co-author, found that secondary forests that were allowed to recover naturally were more successful than “active restoration” projects with manual landings. In other words, manual planting can sometimes even worsen the situation in all respects - from the number of birds, insects and plants, to the percentage of forest canopy coverage, tree density and forest structure. Nature knows better.

Now, Cook-Patton has expanded this rethinking of natural reforestation and the potential for carbon storage. Perhaps these forests do it better.

Hall saysthat this scientific revision also requires a revision of policies. "Business leaders and politicians have seized on the popular tree planting idea, and many nonprofits and governments around the world have launched billions and trillions of tree planting initiatives for a variety of social, environmental and aesthetic reasons."

She admits that on some particularly damaged soils "trees will have to be planted, but this should remain a last resort, as it is the most expensive and often not the most successful option."

Planting a trillion trees in three decades will be a complex logistical challenge. This is a very large number. Achieving this goal will require planting a thousand new trees every second, and so that they all survive and grow. When you factor in the cost of nurseries, soil preparation, seeding and thinning, Kruseile says, the result is hundreds of billions of dollars. Would that make sense if natural forest growth was cheaper and better?