I started thinking about how to approach writing the fourth book on horror design. Throughout October, I tried to find new representatives of the genre that would drag me in, but in the end I started thinking about the concept of horror, about a dream game and how the genre should develop in the future. So why should horror movies be inspired by roguelikes - translation of an article from Gamasutra.

Fear of the unknown

Horror in any form is associated with the unknown - the fact that you find yourself in a situation in which you do not know what will happen. There are a lot of similar iconic moments: a dog jumping out of a window in Resident Evil 1, the first appearance of Pyramid Head in Silent Hill 2, or the moment when you realize what the Outlast hero got into.

This is not the same as in a game like Amnesia, where the developers use amnesia as a way to keep the player in the dark. The story, like the character's memory, will be restored at some point, either for a twist or to complete the game. The best horror is not the “Aha!” Moment when everything is clarified.

The problem with the unknown is that it only works once. The examples from the previous paragraph can only be experienced once by the audience - the next time it will be a regular plot twist that the player will remember.

This is where rogue-like game design can dramatically improve horror. It's worth creating a special kind of randomness.

Definition of randomness

In my book on roguelike game design, I talked about a popular misconception that any random elements will work in the rogue-like genre. This is not true. Good roguelike design comes with a targeted form of randomization and procedural generation (in some cases).

The problem with many screamer horror games is that randomization is not focused on gameplay, but rather on scaring the player. In the Five Nights at Freddy's series, everything is built around a frightening screamer that is about to appear. This kind of randomness does not change the style and approach to the game, usually the gameplay is very mechanical and repetitive. Often in such projects, you can even calculate some patterns.

The best roguelike game designers and their games target specific gameplay aspects that use random or procedural generation. It's not about creating pure chaos, but about having variability that will give you different experiences and sensations. There are horror games focused on procedural generation - this is the most basic variation. But simply changing where the player needs to be is not the randomness we're looking for.

In my concept of a dream game, not only the positions of the opponents change, but also what opponents will appear. In addition, events affecting the game will be randomly selected to force the player to adapt. The best roguelikes give the player a basic idea of what to expect and then force them to adapt to the changes and situations in each playthrough.

Perfect pace

The play session is another area that needs synergy between roguelike elements and horror. The length of the experience is another problem in horror. Feelings of fear are difficult to maintain for long, and there is a limit to how much you can add to prolong it. Adding more enemies or quests will not help immerse the player. Rather, the repetition of situations and play cycles will become tedious.

The longer the horror, the less mysterious it becomes. You can only repeat the plot “this is a strange city where strange things happen” so many times before people get bored, or you try to explain why this is all happening.

Pacing is a problem in the last three Resident Evil games, and the main concern for RE 8. Seven felt too long for its content, and 2 and 3 were too short and consisted of combat most of the time.

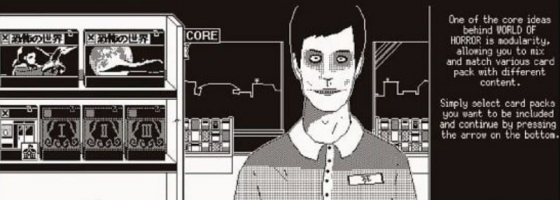

Rogue-like design and pacing are perfect for horror. The upcoming game World of Horror is a good example, which skillfully mixes the mystery of horror with the shortened tempo of roguelikes. A typical gaming session lasts less than an hour, and like any good roguelike, every hour is different from the last.

Micro horror

Another variation in recent times is the idea of micro-games that focus on elements of horror. The Dread X Collection series are compilations of horror titles from renowned indie developers. Each collection has titles made in a short period of time, built on a specific theme and with any design.

The quality and design are very diverse. However, due to the small size of these projects, all attention is focused on unique mechanics. Their duration is enough to understand the essence, enjoy the gameplay and not lose a sense of fear. And it is convenient that they can be purchased immediately in a pack, and not collected bit by bit - you will definitely like some of them.

Battles

Horror games must have a way to "fight". One of the main drawbacks of modern horror games, in my opinion, is the removal of mechanics in favor of nothing. Many developers, like Frictional with the Amnesia series, will defend this, saying combat kills fear and tension.

In a way, this is true, but it's not that simple. The problem with projects like Resident Evil, Dead Space, Alan Wake, and others AA / AAA is that combat becomes a form of filling the game. You can't keep horror all the time in a game with a lot of fights - it just won't work. The same effect will happen when there is minimal interaction with the game.

If the player can only run away, then every dire situation will be tied around it. Instead of thinking on the fly, the game becomes a repetition of the same thing - which again kills the feeling of fear. The fight should not be meaningless, but tactical. The player needs to feel that there are obvious trade-offs in dealing with enemies. And it's not about getting the player to fight constantly, but about adding weight to each experience.

I would like the horror to take on a more “intuitive” form of combat in combination with the short tempo. This is not about dangerous battles fighting 100 enemies, but simply about fighting one. This is why we often think of alpha antagonists like the Xenomorph from Alien Isolation, Mr. X from Resident Evil 2, and of course the Pyramid Head encounters in Silent Hill 2.

Important note: fighting in horror does not always mean “kill”. You can shoot Mr. X as many times as you like, but you cannot kill until a certain bossfight. Enemies should not be triggered by the player, but should be active participants in the gameplay and hunt him during the game. Again, the purpose of all of this is to make the game session more interesting and varied. It should also be ways of interacting with the enemy, not related to combat.

I've lost track of the number of horror games in which the main thing is to avoid and hide without being able to distract enemies.

The future of fear

One of these days I have to sit down and rewrite GDD for my horror idea. And I'm surprised that many developers have not yet taken this path. With the release of Nextgen, it's time to rethink horror designs and combine that with the variety and tension of a good roguelike. We need to stop treating horror games as an eight hour experience based on screamers and skeletons in closets.

There is a middle ground between short indie horror films and large AAA projects. You just need to combine it.

If you are interested in my books on game design, now Game Design Deep Dive Platformers and 20 Essential Games to Study are out. Game Design Deep Dive Roguelikes be released in early 2021.