The fluoroscope for choosing shoes was a dangerous and unnecessary device, but the children adored it.

How do you like the boots? Are your fingers tight? Wide at the ankle? Welcome to Foot-O-Scope - instead of idle guesswork, we offer a scientific approach to choosing the right shoe!

When the German engineer Wilhelm Konrad Roentgen accidentally stumbled upon a mysterious light passing through most materials, leaving a ghostly image of the insides of an object, he hardly thought about shoes. He didn’t even know what kind of light it was, so he called it X-rays, where X meant “something unknown”. The name stuck in English-speaking countries, although in many other languages this phenomenon is called " X-rays ". November 8 marks 125 years since their opening.

From the 1920s to the 1950s, thousands of shoe stores in North America and Europe advertised their shoe selection fluoroscopes, in which the feet of visitors were X-rayed.

Roentgen published his findings on December 28, 1895, and within a month the work "on a new kind of rays" was translated into English and published in Nature . Three weeks after that, it was reprinted in Science.... The popular press began to spread information about the wonderful light that allows you to look inside the human body. Roentgen, following the example of Mary and Pierre Curie, renounced any patents so that mankind could use this new method of studying nature. Scientists, engineers and doctors are immersed in X-ray research.

Experimenters quickly discovered that both static images - radiographs - and moving pictures could be obtained with X-rays. The object under study was placed between the beam source and the fluorescent screen. Roentgen experimented with cathode rays and Crookes tubeswhen I first noticed the glow of a screen coated with barium platinum cyanide. In a few weeks of experimentation, he learned how to get clear images on a photographic plate. The first X-ray image was a photograph of his wife's hand, in which the bones and ring are clearly visible.

Observing the moving image was easier: you just had to look at the fluorescent screen. Thomas Edison, one of the early X-ray enthusiasts, coined the term fluoroscopy for this technology. The technology appeared simultaneously in February 1896 in Italy and the USA.

X-ray from a popular 1896 textbook showing a woman's foot in a boot

Less than a year after the discovery of X-ray, William Morton, a physician, and Edwin Hammer, an electrical engineer, rushed to publish a book entitled X-Rays, or Photography of the Invisible and Its Value in Surgery, describing the apparatus and technology for obtaining X-rays. Among the many illustrations in the book was an X-ray of a woman's foot in a shoe. Morton and Hammer's textbook has gained popularity among surgeons, doctors and dentists who are in a hurry to put this technology into practice.

Feet in shoes have been a popular subject of X-rays since the beginning.

Fluoroscopes for fitting shoes have spread thanks to the military. During the First World War, in 1914, the Military Hygiene and Sanitation Textbook was published, which became very popular. Its author, Frank Kiefer, has included shots of feet in boots to illustrate correct and improper fit. However, Kiefer did not recommend scanning the feet of all soldiers in a row, as doctors and historians Jakalin Duffin and Charles Hayter describe in their article " Bare Your Foot: The Rise and Fall of Fluoroscopes for Choosing Shoes ."

Jacob Lowy, a Boston doctor, used fluoroscopy to examine the feet of wounded soldiers without removing their shoes. At the end of the war, Lowy adapted the technology for use in shoe stores and applied for a patent.in 1919 - however, he received a patent only in 1927. He named his device Foot-O-Scope. On the other side of the Atlantic, in England, inventors applied for a British patent in 1924 and received it in 1926. The inventor of the shoe matching device, pictured at the beginning of this article, Matthew Adrian, applied for a patent in 1921 and received it. in 1927.

Soon there were two companies that became leaders in the production of shoe fluoroscopes: Pedoscope Co. in England and X-Ray Shoe Fitter Inc. IN THE USA. At the heart of the diagram was a large wooden cabinet, at the base of which was an X-ray emitting tube, and above there was an opening into which clients had to insert a shod foot. When the salesperson turned on the device and activated the X-ray tube, the customer could see an image on the fluorescent screen showing the bones of the legs and the outline of the shoe. The devices usually had three eyepieces so that a customer, a salesperson, and a third party (such as a customer's companion) could observe the foot simultaneously.

Machines were touted as devices providing a scientific method for fitting shoes. Duffin and Hayter argue that it was primarily a clever marketing ploy to sell shoes. And it definitely worked. My mother fondly remembers going to Wenton's in Jersey City as a child to buy two-tone leather shoes. She not only managed to look at her feet with the help of fashionable technology - she was also presented with a shoehorn, a ball and a lollipop. The sellers bet on children begging their parents to buy them new shoes.

Exposure risks in shoe fluoroscopes were ignored

Although the fluoroscope supposedly brought a scientific approach to the shoe selection process, it was medically unnecessary. My mother is annoyed to admit that the fluoroscope could not do anything with her bursitis. And because of the uncontrolled radiation exposure, countless sellers and buyers are at risk of dermatitis, cataracts and cancer (with prolonged exposure).

The degree of exposure depended on several parameters, including the person's proximity to the machine, the quality of the device's shielding, and the exposure time. A typical selection lasted about 20 seconds, and, naturally, several clients needed to try on several pairs in order to finally choose the best option. The first cars were not regulated at all. The X-ray, a unit of exposure dose, received international recognition only in 1928, and the first systematic observations of machines began to be carried out only 20 years later. In a 1948 study of 43 cars in Detroit, it was found that they gave out 16 to 75 roentgens per minute. In 1946, the American Standards Association adopted 0.1 roentgens per day as the maximum radiation dose for industrial use of X-rays.

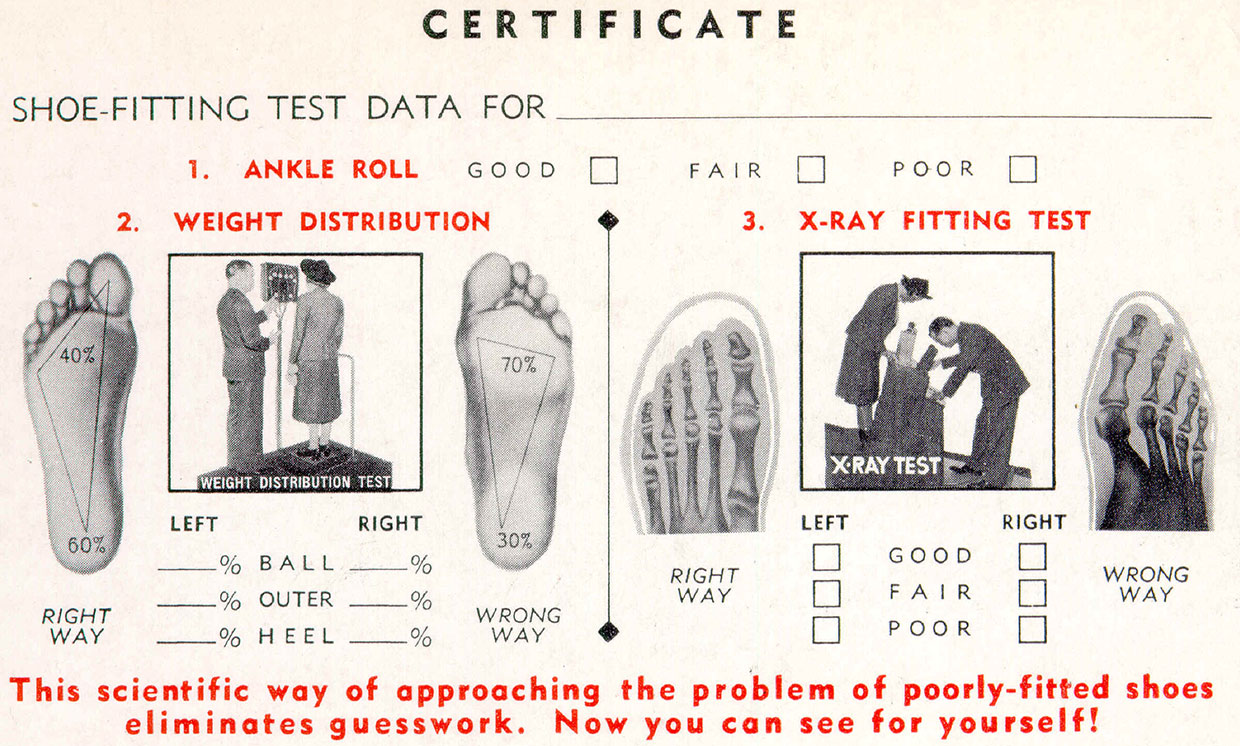

The certificate issued to clients highlighted the scientific nature of the fluoroscope approach.

But some experts warned about the dangers of X-rays from the beginning. One of them was Edison. When Roentgen made his discovery, he was already an accomplished inventor, and for several years in a row thereafter, Edison's laboratory continuously experimented with X-rays. This work ceased after the deteriorating health and the subsequent death of Clarence Dalley.

Dally, a technician at Edison's lab, did many experiments with a fluoroscope, and was exposed to radiation for many hours on a regular basis. By 1900, he had injuries on his arms. His hair began to fall out, and his face was covered with wrinkles. By 1902, his left arm had to be amputated, and the next year, his right. In 1904, at the age of 39, he died of metastatic skin cancer. The New York Times called him a "martyr of science." Edison's statement is well-known: "Don't tell me about X-rays, I'm afraid of them."

Clarence Dalley may have been the first American to die from radiation sickness, but in 1908 the American X-ray community reported 47 radiation-related deaths. In 1915, the British X-ray community issued regulations to protect workers from over-exposure. These rules were included in a set of recommendations issued in 1921 by the British X-ray and Radium Protection Committee. Similar rules appeared in the USA in 1922.

To people who were worried about radiation, a fluoroscope for trying on shoes seemed a dangerous machine. Christina Jordan, wife of Alfred Jordan, a pioneer in radiation diagnostics, wrote a letter in 1925in The Times of London. In it, she decried the dangerous levels of radiation that shop assistants are exposed to. Jordan noted that if a scientist who died from radiation can be honored as a “martyr of science,” then being a “martyr of commerce” is a completely different matter.

Charles Baber, the owner of the Regent Street store, who claimed to be the first shoe seller to use X-rays, responded to the letter the next day. He wrote that he has been using the machine since 1921, and does not observe any consequences either for himself or for his employees. The Times also published a letterEdward Seeger of X-Rays Limited (as Pedoscope was then called). The letter stated that the car had been inspected and certified by the National Physical Laboratory. And this fact, he wrote, "should serve as decisive evidence of the absence of danger for both sellers and users of the pedoscope."

And on this, apparently, it all ended. The shoe-fitting fluoroscope thrived in retail with little or no supervision. By the early 1950s, about 10,000 of these machines were in operation in the United States, 3000 in Britain, and 1000 in Canada.

However, after World War II and the bombing of Hiroshima and NagasakiAmerican atomic bombs, the Americans gradually cooled to everything radiating. We also paid attention to a fluoroscope for choosing shoes. As we mentioned, in 1946, the American Standards Association issued guidelines for the use of the technology. The alarm was raised by reports published by the American Medical Association and the New England Medical Journal. Laws began to appear in the states that only licensed doctors should work with such machines, and by 1957 they were completely banned in Pennsylvania. However, even in the 1970s, they operated in 17 more states. As a result, some of them ended their lives in museums. The device from the first photo is in the collection of historical medical instruments of the Association of Oak Ridge Universities.

The fluoroscope for choosing shoes is a fun technology. It seemed scientific, but it wasn't. The machine manufacturers claimed it was safe, but it was not. As a result, it turned out to be completely unnecessary - an experienced seller can easily pick up shoes without all these frills. Yet I can understand the appeal of these devices. My legs were scanned due to flat feet. I was filmed walking on a treadmill to pick up running shoes. Was it scientific? Did it help? Hopefully. I am sure that at least there was no harm from this.