Does your company want to collect and analyze data to study trends without sacrificing privacy? Or perhaps you already use various tools to preserve it and want to deepen your knowledge or share your experience? In any case, this material is for you.

What prompted us to start this series of articles? Last year, NIST launched the Privacy Engineering Collaboration Space- a platform for cooperation, which contains open source tools, as well as solutions and descriptions of processes necessary for the design of confidentiality of systems and risk management. As the moderators of this space, we help NIST collect available differential privacy tools in the area of anonymization. NIST also published Privacy Framework: A Tool for Improving Privacy through Enterprise Risk Management and an action plan that outlines a range of privacy concerns, including anonymization. Now we want to help Collaboration Space achieve the goals set in the plan for anonymization (de-identification). Ultimately, help NIST develop this series of publications into a deeper guide to differential privacy.

Each article will start with basic concepts and application examples to help professionals - such as business process owners or data privacy officers - learn enough to become dangerous (just kidding). After reviewing the basics, we will analyze the available tools and the approaches used in them, which will be useful already for those who are working on specific implementations.

We will begin our first article by describing the key concepts and concepts of differential privacy, which we will use in subsequent articles.

Formulation of the problem

How can you study population data without affecting specific members of the population? Let's try to answer two questions:

- How many people live in Vermont?

- How many people named Joe Near live in Vermont?

The first question concerns the properties of the entire population, and the second reveals information about a specific person. We need to be able to figure out trends for the entire population, while not allowing information about a specific individual.

But how can we answer the question "how many people live in Vermont?" - which we will further call "inquiry" - without answering the second question "How many people with the name Joe Nier live in Vermont?" The most common solution is de-identification (or anonymization), which consists in removing all identifying information from the dataset (hereinafter, we believe that our dataset contains information on specific people). Another approach is to only allow aggregate queries, for example, with an average. Unfortunately, now we already know that none of the approaches provide the necessary privacy protection. Anonymized data is the target of attacks that establish links with other databases. Aggregation protects privacy only when the size of the sampled group isbig enough. But even in such cases, successful attacks are possible [1, 2, 3, 4].

Differential privacy

Differential privacy [5, 6] is a mathematical definition of the concept of “having privacy”. It is not a specific process, but rather a property that a process can possess. For example, you can calculate (prove) that a given process meets the principles of differential privacy.

Simply put, for each person whose data is included in the dataset being analyzed, differential privacy ensures that the result of the differential privacy analysis will be virtually indistinguishable, regardless of whether your data is in the dataset or not . Differential privacy analysis is often referred to as a mechanism , and we will refer to it as...

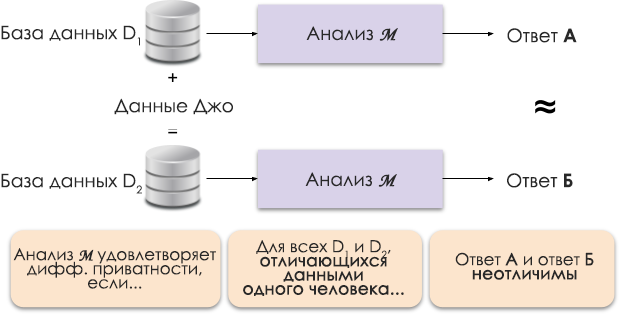

Figure 1: Schematic representation of differential privacy.

The principle of differential privacy is shown in Figure 1. Answer A is calculated without Joe's data, and answer B with his data. And it is argued that both answers will be indistinguishable. That is, whoever looks at the results will not be able to tell in which case Joe's data was used, and in which it was not.

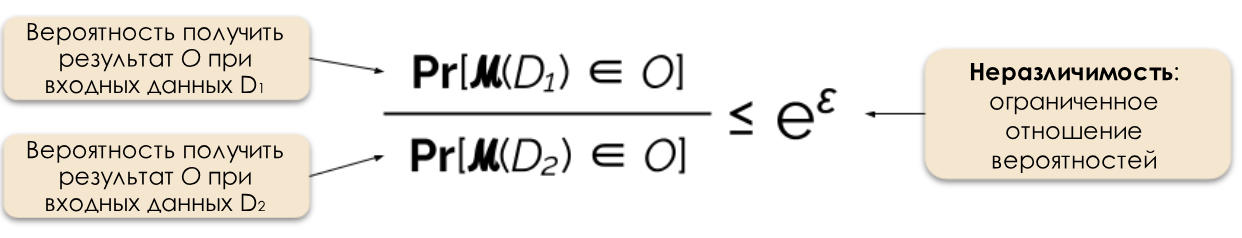

We control the required level of privacy by changing the privacy parameter ε, which is also called privacy loss or privacy budget. The smaller the ε value, the less distinguishable the results and the more secure the data of individuals.

Figure 2: Formal definition of differential privacy.

Often we can respond to a request with differential privacy by adding random noise to the response. The difficulty lies in determining exactly where and how much noise to add. One of the most popular noise noise mechanisms is the Laplace mechanism [5, 7].

Increased privacy requests require more noise to satisfy the specific epsilon value of differential privacy. And this additional noise can reduce the usefulness of the results obtained. In future articles, we'll go into more detail about privacy and the trade-off between privacy and usefulness.

Benefits of differential privacy

Differential privacy has several important advantages over previous techniques.

- , , ( ) .

- , .

- : , . , . , .

Due to these advantages, the application of differential privacy methods in practice is preferable to some other methods. The flip side of the coin is that this methodology is fairly new, and it is not easy to find proven tools, standards and proven approaches outside the academic research community. However, we believe that the situation will improve in the near future due to the growing demand for reliable and simple solutions to preserve data privacy.

What's next?

Subscribe to our blog, and very soon we will publish the translation of the next article, which tells about the threat models that must be considered when building systems for differential privacy, as well as talk about the differences between central and local models of differential privacy.

Sources

[1] Garfinkel, Simson, John M. Abowd, and Christian Martindale. "Understanding database reconstruction attacks on public data." Communications of the ACM 62.3 (2019): 46-53.

[2] Gadotti, Andrea, et al. "When the signal is in the noise: exploiting diffix's sticky noise." 28th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 19). 2019.

[3] Dinur, Irit, and Kobbi Nissim. "Revealing information while preserving privacy." Proceedings of the twenty-second ACM SIGMOD-SIGACT-SIGART symposium on Principles of database systems. 2003.

[4] Sweeney, Latanya. "Simple demographics often identify people uniquely." Health (San Francisco) 671 (2000): 1-34.

[5] Dwork, Cynthia, et al. "Calibrating noise to sensitivity in private data analysis." Theory of cryptography conference. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006.

[6] Wood, Alexandra, Micah Altman, Aaron Bembenek, Mark Bun, Marco Gaboardi, James Honaker, Kobbi Nissim, David R. O'Brien, Thomas Steinke, and Salil Vadhan. « Differential privacy: A primer for a non-technical audience. »Vand. J. Ent. & Tech. L. 21 (2018): 209.

[7] Dwork, Cynthia, and Aaron Roth. "The algorithmic foundations of differential privacy." Foundations and Trends in Theoretical Computer Science 9, no. 3-4 (2014): 211-407.