If you catch a student and shake him properly with the question of what a rudimentary organ is, he will most likely answer you that it is something unnecessary. If you have a Soviet schoolchild in front of you, then I would like to believe that the answer will be fuller - they will tell you that “rudimentary” means an organ that has lost its significance in the process of evolution, from the Latin “rudimentum” - an embryo, a fundamental principle. Then you will probably get bream from an educated adult, but these are details.

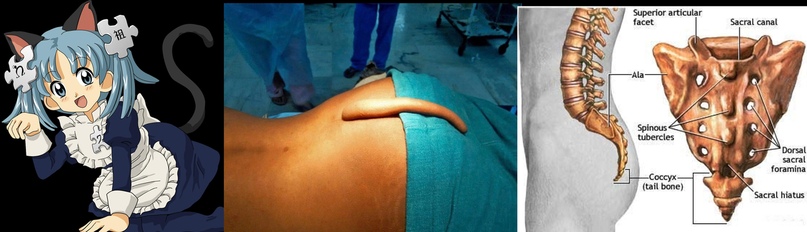

However, most articles on rudiments begin with the most obvious examples. One of the most popular, in the spirit of our time, in the fifth point is the tailbone. Lost tail. The first thing that comes to SV's fevered imagination is a cute Japanese schoolgirl with a decorative ponytail and mittens. But life is not like that. In fact, all mammals have a tail, but only at some point in their development. Specifically in the human body, it is present at the stages of embryogenesis from 14 to 22 - this is from the 33rd to 51st days of fetal development. And those in whom it does not reduce as it ripens, outwardly so far from being cute that they prefer removal.

It is believed that the tailbone, located at the end of the spine, has lost its original function of maintaining balance and mobility, ceasing to be a tail. But this is where the problem of reduction lies. Do we all really have spare parts? The inner tail is still good for something. It performs secondary functions, being the anchor point for the pelvic floor muscles, tendons and ligaments. Which, in principle, explains why he did not disappear completely.

In order to make sure that we are not alone, we need to dive deeper into science and into the sea. We are interested in the baleen whale, northern smooth whale and / or dolphins. Their legs completely disappeared during the descent into the sea. If Georgiacetes (the ancient ancestors of cetaceans) swam on all four, then to find the remains of the pelvic bones in a whale, you will have to delve into its anatomy.

- - . “” , . , , . , , . , . , .

, , , , , , , . , . , , , . , , . ? , . . , - .

, ? , , . , “” . , SV , . , , . , , - . -, , . - . . .

. , , . , () - , . . - , , , , . , , . 6 . , , , , .

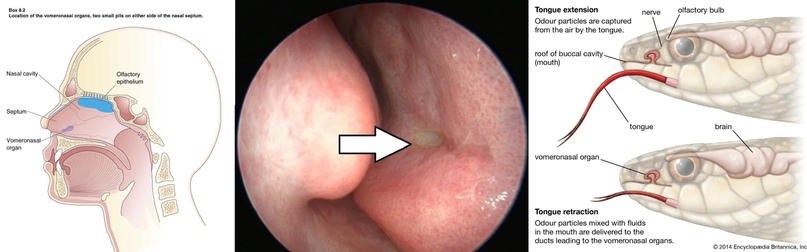

, , , , . . , -, . , (. ), , , , , , , , , , . , (). . , , , , . (Won, J; Mair, E. A.; Bolger, W. E.; Conran, R. M. (2000). "The vomeronasal organ: an objective anatomic analysis of its prevalence". Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal. 79). . . , ... , ? ? ? . , , …

. , ( ) . , .

, . , , - , , , . , . «» , , , .

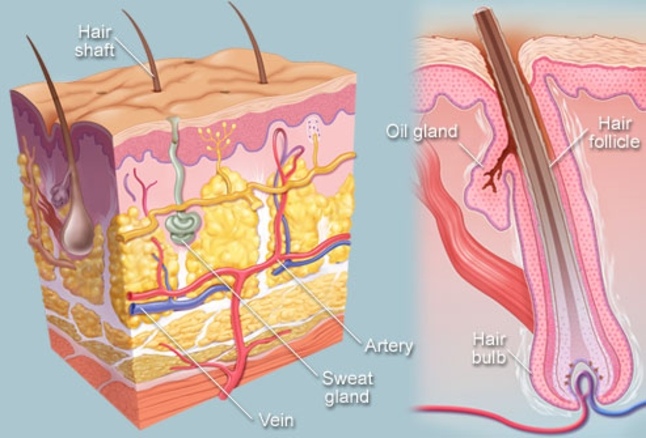

, , , , . , . , . , , . , , , . , , , , , . , , , .

. , - . , . , , . 40 , .

, , , . , , - . . . ? . , , , .

, , , , . , , , , - . , . .

. , , (), .

, , , , , . , , . , , . , « ». , .

, . , « ». , , , . - , , , . . “” , , , . .

? , . , : , . , . . , , , , , . , , - (Trichechus manatus). . , , . . . .

( ), , . , , . , - , , , , ( !). … , . , . , . , . - , Sotalia guianensis. -, .

, . , , , - - . , , . , . , , -- , . , , . 220 , . , 4,6 - . , .

. , , . - , , . , , .

What do I want to say? There was once a popular phrase about "inscrutable ways of the metaphysical." Now it is perhaps relevant in relation to natural selection. Seven billion chains of hereditary mutations, congenital diseases and combinations of immunity and anatomy are in free float. It is impossible to predict what they have reduced, and what else will come back and sparkle with new colors of sexual attractiveness and success in sexual reproduction - antennae, painters, virtuoso ears.

Your SV.