I really like board games, and therefore I could not pass by an article about how similar games a couple of centuries ago helped people learn the world. I want to share with you the translation of the history of geographic entertainment by Valentin Colton. I am sure that this story was not the only one that hooked me.

In 1795, Henry Carington Bowles released Bowles' European Geographic Entertainment, or Geographical Game, the latest in a series of games produced by his family. Based on the travel story, Dr. Nugent's Grand Tour of Europe from 1749, Bowles skillfully combined well-known English vanity with simple rules. Embarking on an "elegant and instructive tour of Europe," the players took turns rolling an octagonal ball and moving their post chips across the appropriate number of cities. Whoever returned to London first "had the right to applause and was honored to be considered the most erudite and most agile traveler": an enviable but deceptive praise. In fact, in Bowles' game, erudition and speed were opposed to each other.The "enlightened" player had to "linger" on the playing field, missing a few moves.

The same Bowles' European Geography Game, or Geographical Game, 1795

For example, on the first die roll of five, you will be taken to Blois, a “pleasant town on the Loire,” where you “decide to stay two turns to learn to speak "Pure" French ".

The next shot is six points for a total of eleven. And you stop in Bordeaux for a short while to indulge yourself with a good claret (red wine). This is followed by a series of less "fun" places. On turn forty-one you will find Ferrara, “once a thriving city, but in decline, since some time ago it fell under the subordination of the Pope,” and learn that “this is such an unfortunate place that the traveler must return to field 7 - to the city of St. Malo (a town on the coast of the English Channel, the English Channel).

This route didn't make a lot of sense for navigation, but it was an example of ardent anti-Catholicism in the game. In fact, Rome was recognized as "once the master of the world, but now only the capital of the papal possessions", so you had to "examine its wonders and reflect on the abuse of power by the papal government" two (!) Times. Unsurprisingly, players raced back to London, applying the principle that Gustave Flaubert immortalized in his Dictionnaire des idées reçues: "Travel must be fast."

Of course, in 1795 no one traveled downright fast. It took decades for passenger ships and trains to evolve into some sort of trains and cruise ships, leaving the charm of the Grand Tour (French Grand Tour - a designation adopted since the Renaissance for compulsory travel made for educational purposes by sons of noble families Europe (and later from wealthy bourgeois families)) accessible only to

wealthy people . In the end, even the elite were tied to home, as the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars virtually closed the continent to the British. While the penchant for comparing pandemics to military crises is in many ways pernicious, they have one thing in common: borders are closed.

Just like during COVID-19, the Georgians went on virtual tours. Without live broadcasts, they had to settle for travel notes and maps, and a new product that synthesized them: the cartographic board game.

Pierre Duval, Le Jeu du Monde, 1645

The Bowles family was not the first to produce such entertainment. The pioneer here was Pierre Duval, whose Jeu du Monde (1645) organized the "world" into something like a spiral of a snail's shell, starting with "1. Polar world "and ending with" 63. France ". Duval is more of an adapter than an inventor. It was inspired by the game Jeu de l'Oie (“ The game of the goose"), Which was popular in Europe in the sixteenth century. Sixty-three play areas and the ability to place bets are two characteristics of the game that Duval adopted from the predecessor Goose. However, his own game, which was based on a playing field in the shape of a spiral, was quite understandable in training. And she didn't force the players to linger on the field to learn something instructive. Individual cities lacked emotional descriptions, so players wasted no time learning other languages or discovering the horrors of Protestantism. Didacticism, or "didactic", became a part of the game much later, when the model finally found itself on the other side of the English Channel thanks to John Jefferies' 1759 game "A Journey Through Europe" or "Game of Geography". However, during that century-long hiatus, the game took on a completely different form.

Jefferies replaced Duvall's spiral with a Mercator projection, ignored the convention of sixty-three playing fields, and rejected any association with gambling. Instead, he became the first to return to "On field 77, you win the game in London, receive the honor of kissing the hand of the King of Great Britain, be knighted, and receive compliments from the entire company on your new status." Fully monarchical rules state that players hitting "any number where the king lives" will be eligible for a double roll. Let us recall that at that time the Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was going on. Would anyone sent by Frederick II to Berlin have received the helping hand of Louis XV?

Jefferys' Journey to Europe or Game of Geography, 1759

Although Voyage Europe lacked political savvy, it did welcome knowledge and seemed to double the number of “didactic stops”. In Frankfurt an der Oder, you need one turn to buy the "Black Typewriter to Send to England". You will also need to make an extra turn in Mainz "to see the art of printing discovered there by John Faust in 1440." Amazingly, you will even know how to use it when you return. Unless, of course, you are "captured" by the papacy. Any visitor to Rome was supposed to "kiss the Pope's toe" and be "banished for madness on Field 4 to the cold island of Iceland and miss three moves."

These rules are similar to the Bowles rules. So we might be seeing plagiarism in board games. Our earliest extant copy of A Journey through Europe contains the line: “Printed for CARINGTON BOWLES, Map & Printseller, No. 69 at St Pauls Church Yard, London. Price 8 shillings. " This address goes a long way in explaining what happened next.

It has been the backbone of the family business since the late seventeenth century, when Thomas Bowles I began publishing. His eldest son Thomas II took over in 1715, while his younger brother John opened his own store, first at Mercers Hall, Cheapside, then Black Horse, Cornhill. Each brought his son to the enterprise - Thomas III and Carington I, respectively. But the branches were reunited when the early death of Thomas III forced Carington I to return to St Paul's Cathedral in 1763.

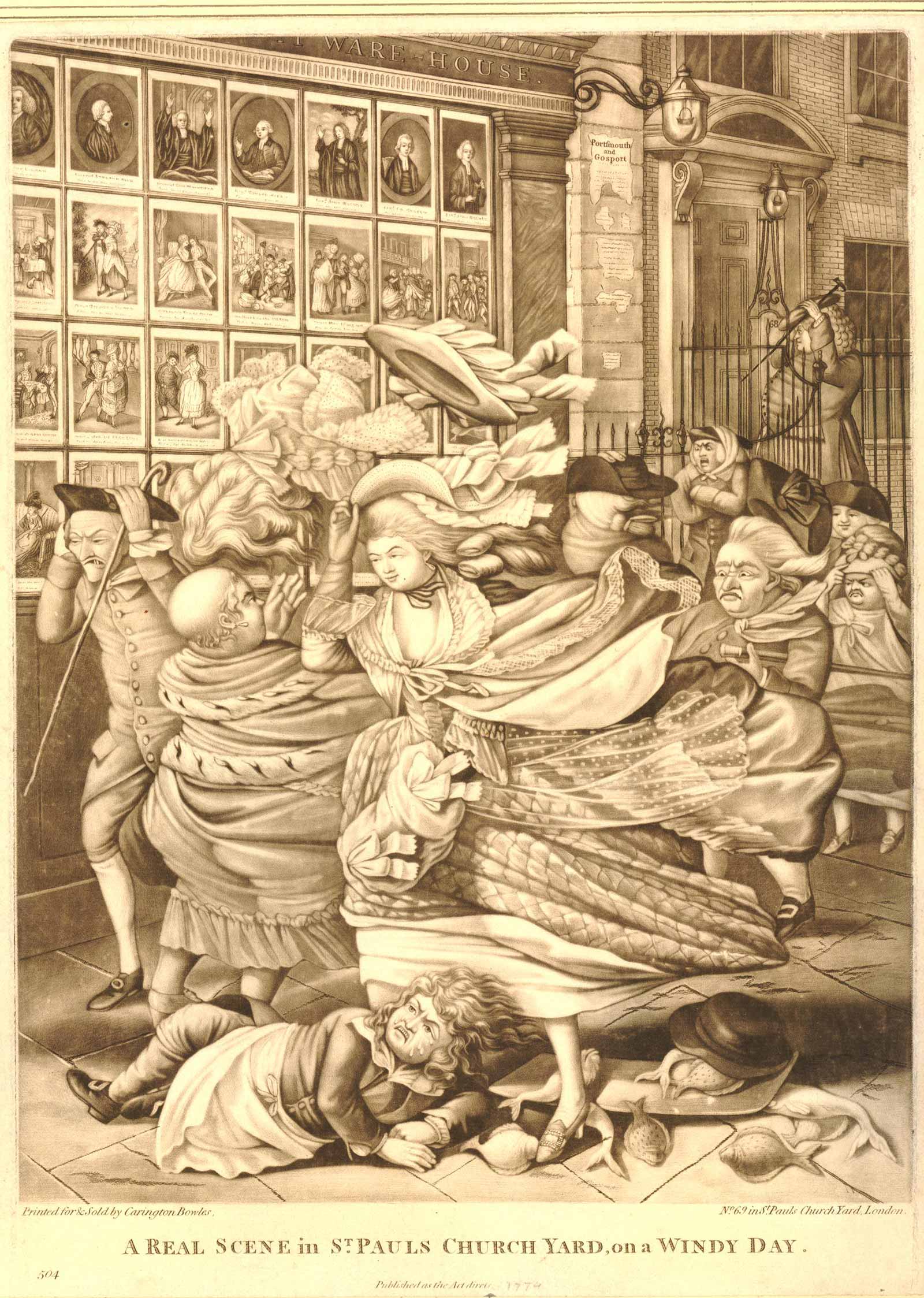

In those 150 years, the Bowles printed everything from mezzanine portraits such as John Dryden George White (1698) and Jonathan Swift Thomas Burford (1744) to landscapes and political satire. Take a closer look at the printed Real Scene of Dayton in the Courtyard of St. Paul's Church on a Windy Day (1783). In addition to the scattered fish and flying hats, you will also see their own prints.

The actual scene of Daytona in the courtyard of St Paul's Church on a windy day, 1783

And then it was time for the cards. In the early eighteenth century, the firm acquired the cartographic stocks of Morden & Leah and John Seller, which formed the basis of the Bowles family's centennial printing era. These were pocket maps of common people from London, Westminster, and Southwark (1725) and meticulous improved maps of Wiltshire (1763). Focusing on Jefferies' work, Carington Bowles easily adapted these cards to the format of a board game: one large image, cut into sixteen rectangles, glued to the canvas, and then folded into a portable case.

Over the next decades, he and his developers released many games. First there was Royal Geographical Entertainment, or The Traveler to Europe (1770), which caused serious legal disputes with the royal geographer Thomas Jefferies (namesake of the previously mentioned Jefferies). Then there was Bowles' British Geographical Entertainment (1780), which focused primarily on local geography, along with The Most Complete and Elegant Tour of England, Wales and Adjacent Parts of Scotland and Ireland. Of the more global projects, one can note Bowles 'Geographical Game of the World (1790), and of the virtual tours across the continent struck by revolutions, Bowles' European Geographical Entertainment (1795). New editions went on sale with current geopolitical updates.At the end of the century, there was no longer a "monarch rushing to the banks of the English Channel" in Paris. Instead, the player paused for two moves "to contemplate the new French constitution, to inspect the Palace of Versailles and the Bastille monument destroyed in 1789".

What drove the demand for these games? In addition to the dreadful boredom, there was a rapid expansion of trade networks and the British empire, making geographic knowledge increasingly convertible into economic and cultural capital. High schools insisted on including in the educational curriculum, along with arithmetic and modern languages, the works of such reformers as John Clarke and John Holmes. And on Grab Street, publishers published reference materials, encyclopedias and school textbooks. In the 1760s, John Spilsbury entered the market with his mahogany “split cards”: the ancestor of modern puzzles. Less joyful was the reaction of King George II to the Jacobite uprising in 1745: a careful survey of the Scottish Highlands led to the creation of the Ordnance Survey in 1791, still an existing national mapping agency. General William Roy said: "If a country has not actually been surveyed or little is known about it, war can fill the geographic knowledge gap."

So what became Bowles' geographic entertainment: an entertainment for a bored people or a tool for educating a new generation of imperialists traveling the world? In any case, the cultivation of such imperialist values has probably proved beneficial to Britain. When the continent became open again after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, a new era began in travel history. Using new ways of transporting passengers (meaning steamships and railways), guided by the innovative guidebooks published by Murray and Baedecker, the British rushed across the English Channel in large numbers: about a hundred thousand a year by 1840. During the nineteenth century, tourism replaced the Grand Tour. Point travel has supplanted long travel across the continent.

At least that was until mid-March. We are now like the English of the past as we stay to read and play board games, postponing the idea of a beach holiday and study abroad until everything is restored and the borders are open again. When will this happen, and will the borders open again? Or will viral phobia push the hostility towards tourists?

For William Hazlitt, travel was about impermanence. "This is an animate but temporary hallucination," he wrote. “It takes an effort to change our reality. To feel very acutely the pulse of our usual life, we must "jump" over all our present conveniences and connections. Our romantic and itinerant nature cannot be changed. " Perhaps this is what we will remember when freedom of movement is restored: we do not leave home in order to “be considered the most educated and fastest traveler,” but for the sake of knowledge, surprise, illusory bliss from the fact that we go out for a short time. the framework of the familiar.