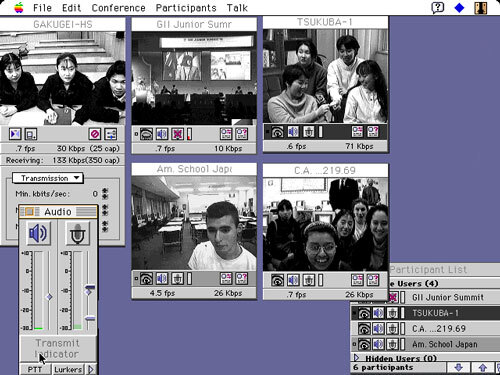

Screenshot of CU-SeeMe - one of the first Internet video conferencing systems that appeared back in 1992. In the business environment and the defense industry, examples of the use of video conferencing technologies have arisen back in the 1980s.

Despite four decades of technology evolution, low-level video conferencing is essentially magic that doesn't work half the time. In this article, I'll explain why this is happening.

In a world frightened by the spread of a life-threatening disease, sooner or later employers would inevitably ask employees to stay at home ... and work from there. This advantage was most often not enjoyed by workers in the past; it became possible thanks to the Internet. But the Internet is far from ideal for this kind of application, and it proves it almost every time you start a video conference. Small delays cause people to interrupt each other. Time is wasted because the interlocutors have to repeat what was said. And there will always be one colleague who decides to work in a cafe with all the noise surrounding him. Personally, I have been working remotely for almost four years, so I was often given the opportunity to make conference calls; I realized there were problems with them - technical, cultural, and practical.And many of the difficulties this technology poses boil down to the many small features of the Internet. Today we'll talk about the complexity of the video conferencing system.

“A lot of video conferencing is a terrible waste of money; they don't provide any advantage over voice conferencing because users don't know how to harness the potential of the visual component. " - This is a quote from a 1992 columnist in Network World by James Kobelous, who noted that many companies have invested heavily in interoffice video conferencing technologybut failed to make them more effective than simple phone calls. At the time, they had literally no advantages to modern technology. This is what a standard video conferencing system looked like in that era, according to the article: “Typically, video conferencing can use parallel remote audio transmission, fixed and mobile internal microphones, multiple swivel wall cameras, stands for still and motion graphics (with the camera in hand speaker while he draws), 35mm slide projectors, VCRs, fax machines, electronic interactive whiteboards and personal computers.

Video conferencing technology required many innovations to gain widespread popularity

Yes, conference calling technology is a little frustrating even in 2020, but it's worth saying that we've come quite a long way over the years. Even though video conferencing technology remains annoyingly flawed, it still reflects our four decades of troubleshooting efforts.

Since its introduction to workplaces in the 1980s, video conferencing equipment has come a long way. For many companies, acquiring it came with a five-zero cost, and the hourly cost of each call was much higher (up to $ 1,000 / hr) compared to the salaries of the day.

(Perhaps this is reflected in the fact that in many of the first video broadcast system applies a "one transmitter, several receivers," in which we used the same technology as the cable or satellite TV. They were not interactive, but it works.)

With on the other hand, in just a few years, video conferencing technologies have improved significantly, and their prices have decreased tenfold. In 1982, when Compression Labs released its first video conferencing system, it cost $ 250,000, but prices were falling rapidly - by 1990 it was possible to buy a ready-made system for as little as 30,000, and by 1993 - less than 8,000 .

But implementing video conferencing had to make many compromises. T1 lines could transmitapproximately 1.5 megabits of streaming data per second. That bandwidth would be roughly enough to watch a single YouTube video at 480p, and in the 1980s it cost thousands of dollars to purchase. (Because of its multi-line structure, which was supposed to be the equivalent of 24 separate telephone lines, T1 lines remain very expensive today, even though fiber has overtaken them in speed.)

Drawing from a 1987 patent application issued by Compression Labs. It describes one of the first two-way video conferencing technologies. ( Google Patents )

Over time, this led to variants of systems using less powerful networks for video conferencing, such as Compression Labs Rembrandt 56, which used ISDN lines, which at that time reached a maximum speed of 56 kilobits / s. These $ 68,000 systems, which leveraged Compression Labs' video compression innovations, have enabled consumers to reduce costs by about $ 50 / hour . (Note: In the 1980s and 1990s, teleworkers used ISDN most often.)

As you can imagine, videoconferencing primarily flourished in government offices in the beginning, and many of the early research on the applicability of such technologies was usually conducted by the military.

"Video compression involves the inevitable trade-off between image resolution and motion processing capability," says a 1990 dissertation by a student at the US Navy's Advanced Training School, which outlines videoconferencing guidelines for the ROCA. “Image quality depends on the bandwidth. As the bandwidth decreases, more coding is required, resulting in degraded images. "

It is also worth noting that video conferencing became an important element in the advancement of image compression technologies throughout the 1980s. In fact, Compression Labs, responsible for many of these innovations, became a source of controversy in the 2000s - it was acquired by a new owner who tried to exploit a patent on a compression algorithm used in JPEG format to sue large corporations . The patent troll settled a dispute with many major technology companies in 2006 after a court found that the patent was for video-only applications.

Consumer-grade video conferencing technology (i.e. webcams) was introduced in 1994 with the release of Connectix Quickcam, a device that I am intimately familiar with.... This $ 100 device did not perform well on older PCs due to the limited bandwidth provided by parallel ports and other older gadgets; however, it led to further innovations that continued for several decades. (The USB and Firewire ports — the latter used in the iSight camera that Apple sold in the early 2000s — provided enough bandwidth to record video or even stream it over the Internet.)

Major innovations were also emerging in the corporate sector. In 1992, Polycom released its first conference phone- a device that allowed several people to talk in one office; in this format, conferences continued to be held for the next three decades. A few years later, WebEx, which was later acquired by Cisco , developed one of the first video conferencing technologies for the Internet, which we still use today.

Video software technologies were greatly enhanced in the early 2000s by Skype, whose ability to provide high-quality video and voice conversations over a peer-to-peer network has become a major innovation in conferencing technology. However, after being acquired by Microsoft, Skype switched from a peer-to-peer scheme to a supernode system.

By the mid-2000s, webcams had become standard components of laptops and desktops. The idea itself was proposed back in 2001 in the Hewlett Packard Concept PC , and the first computers with built-in webcams were the iMac G5 and the first generation MacBook Pro with Intel processors.

So, we have this whole set of gadgets, allowing us to communicate with each other almost without the slightest problem. But why are we unhappy with this? There are several reasons for this.

1,5 / — , Skype . ( T1.) VoIP- Microsoft 100 /, . , .

- Polycom -.

-

To answer the question of why office video conferencing continues to face so many challenges despite all the innovations, we need to take a step back and consider that we are striving to accomplish many tasks on very precarious foundations.

We have all these innovations, but they compete with a lot more resources.

If you are sitting at home in front of a laptop connected to a 100 megabit fiber-optic channel, then there is a possibility that you are streaming a video game to the next room while downloading 15 torrents, but you still won't experience any special problems.

But if you are in an office with a hundred more people and this office holds several videoconferences every day, then this has a very high load on the office Internet.

Here's an example of a situation that might arise today: Let's say there is a general meeting in the afternoon, but you have a deadline, so instead of walking fifteen meters to the conference room, you decide to join the meeting online. Let's say ten of your colleagues have decided to do the same. Even though you are all in one large room, none of these connections are made locally. You are connecting to a meeting on a local network over the Internet, which means that this local network not only has to upload a bunch of additional data to the Internet, but also download it back.

If you, for example, work at Google, where a large-scale network infrastructure is built, then this may not be a serious problem. But in smaller companies, a corporate network can be extremely expensive, costing hundreds or thousands of dollars a month, not counting installation costs . As a result, at some stage, you can run into the ceiling of your capabilities.

Suddenly, the video conferencing, which is supposed to serve remote users, starts to slow down and stutter. (This might be one of the reasons the IT folks are recommending that you don't load Dropbox on your work PC.)

But even small moments of delays can create serious problems. Have you ever had your words superimposed on another person's speech? This happens when a small delay creeps into the signal. And since video and sound are often transmitted in different ways (sometimes even by different devices), these delays can cause synchronization problems - for example, situations in which the sound moves faster than the interlocutor. Video conferencing company 8x8 claims that 300 milliseconds is acceptable latency for a video call, but that latency is enough for two people to start talking at the same time. (Perhaps you need a system like in walkie-talkies ?)

Many modern webcams are just not very good, especially if they are built into a laptop screen.

Why conference calls don't work well outside the office

But even if you are at home or on the road, most likely, there will still be problems that prevent you from providing high-quality sound and video; and they are not always related to the width of the Internet channel.

Some of the issues will be related to noise, some will be related to camera quality, and some will be related to sound settings.

As for the quality of cameras, an interesting phenomenon has emerged in recent years: in fact, we are interested in improving the quality of cameras, but at the same time we are striving to reduce the size of the lens, which leaves not much room for improvement. In fact, cameras have nowhere to go - you need to either miniaturize technology, or try to implement elements that turn out to be more controversial than useful. The most notorious example was the Huawei Matebook Pro - the designers decided to place the camera under the flip-up key, and this turned out to be the most controversial aspect of an otherwise good laptop.

All this is happening at a time when the importance of camera clarity is constantly increasing, which means that laptop webcams are significantly worse than their mobile counterparts - for example, the 16-inch MacBook Pro uses a 720p webcam . And this is today, when many modern smartphones are able to shoot video from front cameras in 4K resolution. Even if streaming does not handle full resolution, there is a chance that lower compression levels will improve quality.

Speaking of compression levels, the new fashion for getting rid of headphone jacks has created a pretty serious problem for conference calls. To put it simply, most versions of Bluetooth traditionally have a fairly mediocre sound quality when using a microphone.This is due to a particular problem with the Bluetooth specification that has plagued the technology throughout most of its history: it is impossible to get high-quality microphone sound from the specification due to lack of bandwidth; the situation is aggravated if the device is connected to a 2.4GHz WiFi network, which has the same frequency as Bluetooth.

In fact, the sound quality of the microphone drops significantly when using a Bluetooth headset. Although Bluetooth 5.0could potentially provide bandwidth to improve headset microphone sound, this standard is mostly supported only by the most modern PCs and smartphones. The fact is, if you want to connect to a video conference, you just need to plug in your wired headphones, even over USB. I found that even sophisticated wireless noise canceling headphones, such as the Sennheiser PXC 550, are problematic to use as a microphone in video conferencing. (Today I use the much more hyped Sony WH-1000XM3, but despite all the effort I put into developing their microphone, when I need to make a call, I plug in the headphone cable with the built-in microphone.)

It is also worth noting that ordinary phone calls to a number can have a similar effect on call quality, because voice lines are usually heavily compressed . (It is for this reason that music on hold sounds especially awful .) If you have a choice between dialing and calling via an app, then choose an app.

When it comes to sound, consider the environment as well. Highly echoed rooms are not particularly suitable for conference calls. While working in a coffee shop can spur your creativity, you won't be able to find a quiet space to chat (or a fast enough Internet connection).

But on the background noise front, there is good news - there is technology that allows the microphone to cope with the sounds of frappuccino blenders. The Krisp app for macOS, Windows and iOS uses artificial intelligence to eliminate a lot of background noise. Although not free, it can improve sound quality. For Linux users, there is also a rather effective option - in the pulseaudio application, you can enable an option that removes background noise from recordings in real time. (It's not as high-quality as Krisp, but it's free!)

A similar innovation on the video front — background blur — has appeared in major video chat tools like Microsoft, Teams, and Skype .

Soon we will be able to participate in video conferencing from Starbucks with the same quality as at home.

But even if you've chosen the right headphones, got rid of all the ambient noise, found the perfect room, and got it right, you won't be able to get rid of the fact that everyone else in the conference needs to create a comfortable environment on their own. And if one of the interlocutors decides to participate in a conference with a window open to a noisy freeway or connecting via the world's worst wireless network, does not know about the existence of a mute button or decides to communicate in pajamas ( or even worse ), then the whole communication process will certainly go downhill. And nowadays, when people are forced to work from home, they may not have a plan B.

In many ways, this is more of a cultural than a technical issue, but it can be explained with a concept more closely related to cybersecurity than video meetings: the attack surface. The more people attending a conference, the larger the attack surface and the more likely it is that one weak link will spoil the entire conversation.

Let's be honest: While video conferencing software isn't perfect, it has come a long way and is now, in principle, good enough to allow you to work regularly from home without affecting the quality of the work.

A great example of this is e-learning, an educational version of video conferencing that is considered so effective that it has essentially become a common practice in the event of snowfall in some areas.

Considering everything we can do with the Internet and the sheer volume of data transferred, one can only marvel at how well video conferencing does its job. And it often takes a lot of compression and quality degradation to get it done. It is because of this that we have to repeat our words too often. Perhaps, on the contrary, we should be surprised that our colleagues almost always hear us.