Theologians Develop Sacred Rituals for Corporations and Their Spiritually Depleted Employees

Combining the obscure language of the sacred with the obscure language of management consulting, the agencies provide spiritually oriented services to corporations.In the

beginning there was the coronavirus, and the white collar tribe tore off their clothes, because their working days were a shapeless abyss, and all their rituals disappeared. New customs replaced old ones, but they were scattered, and chaos reigned over how to properly exit a conference to Zoom, hire interns, or end the work week.

But the lost can still find their meaning, for a new corporate clergy has emerged, formalizing the working life at a distance. They are named differently: ritual consultants, spiritual developers, soul-oriented advertisers. They have degrees from schools of theology. They are committed to bringing religious traditions to corporate America to enhance spiritual wealth.

Simply put, theology schools used to send their graduates out into the world to lead congregations or conduct scientific research. But now there is a calling that connects them to their offices: a spiritual advisor. Choose this path established agencies (some commercial, some - no) with similar names: Laboratory sacred design [Sacred Design Lab], Laboratory ritual design [Ritual Design Lab], Ritualist [Ritualist]. They combine the obscure language of the sacred with the obscure language of management consulting to deliver spiritually oriented services to corporations - from architecture to employee training and ritual development.

Their big goal is to soften cruel capitalism, to make room for the soul there, to encourage workers to wonder if what they are doing is good in the highest sense. They have already seen how corporate culture happily includes social justice, and now they want to know if there are still businesses in America that are ready for faith.

“We've seen brands enter the political space,” said Casper ter Kühl, co-founder of the Sacred Design Lab. Commenting on a report from Vice , he added, "The next vacancy in advertising and brands is spirituality."

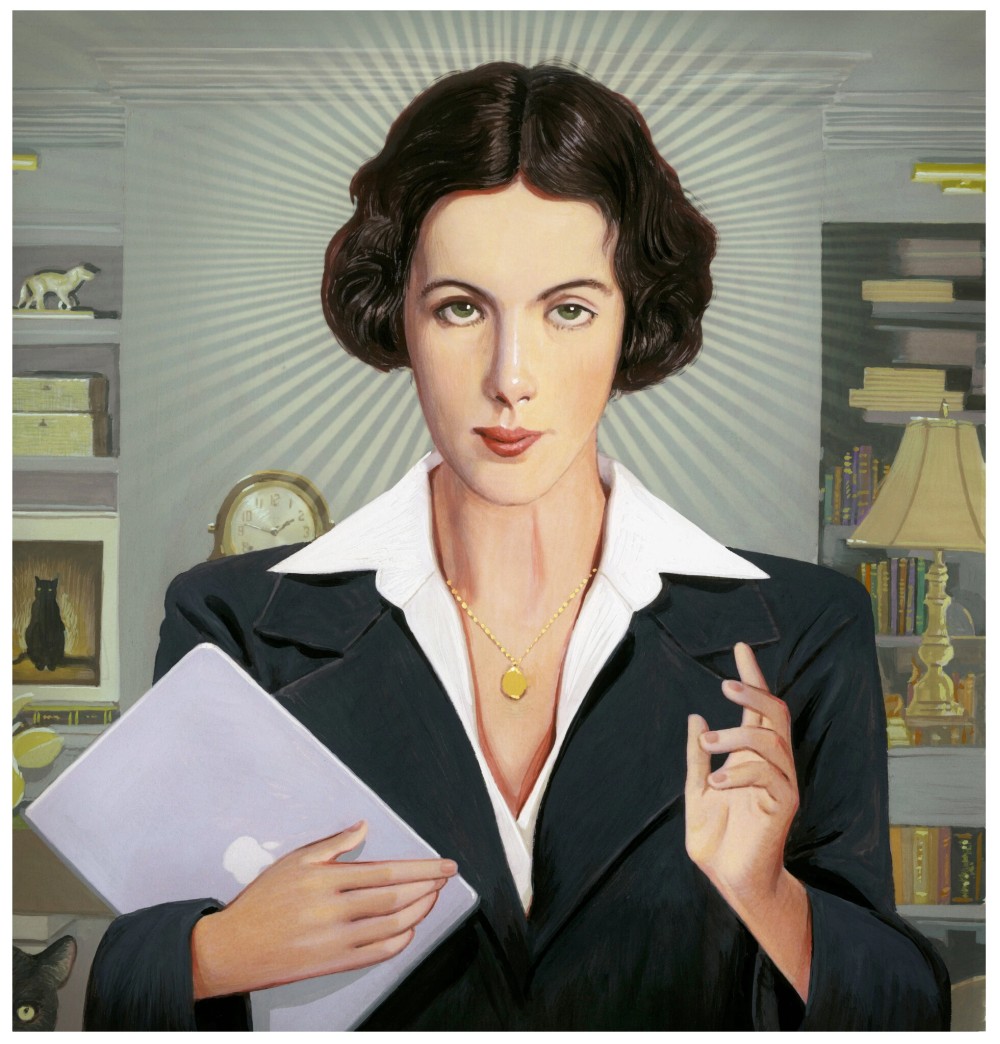

Casper ter Kewle of Spiritual Innovation at Harvard Theological School, co-founder of the Sacred Design Lab

Before the pandemic, these agencies made ends meet by helping design companies - improving products, offices, and branding. They also consulted on strategies, workflow and HR management. And since digital workers have been at home since March, they have a new opportunity. Employers see workers become fragmented and anxious and seek advice on how to rally them back. Spiritual guides are now helping to create new rituals for shapeless working days and provide meaningful practices to workers.

Ezra Bookman founded Ritualist in Brooklyn last year, describing itself as "a boutique consultancy that transforms companies and communities through the art of ritual." He has devised rituals that small firms can perform when events such as the successful completion of a project - or, in the event of a failure, a funeral of a project occur.

"How can you help people cope with grief when a project fails and help them move on?" - said Bookman. Startup Instagram

postslook like a kind of menu for companies choosing operational ceremonies: "The ritual of buying a domain name (or your virtual place in the clouds)." “The ritual after receiving an email from LegalZoom informing you that you are officially registered as an LLC” [something like LLC / approx. transl.].

"People Will Quote SoulCycle"

The fashion for spiritual consultants may have originated from the co-founders of the Sacred Design Lab - ter Cule, Angie Thurston and Sue Philips. They met at Harvard Theological School, where they are still in the Department of Spiritual Innovation, and founded their non-profit organization in 2019.

Their experience is different. Ter Kewle, who lives in Brooklyn, hosts one of the popular Harry Potter podcasts , and has written a book on how to "turn common daily habits - yoga, reading, dog walking - into sacred rituals." Thurston living in Alexandria, pcs. Virginia, was looking for spiritual connections between people of different faiths. Phillips from Tacoma, pc. Washington is the priest of Unitarian universalism .

What brings them closer is their agreement that the institutions of traditional religions are no longer working, and corporate culture is mostly spiritless.

At Harvard Theology School, students have been studying the trend away from organized religion for decades. They agree that while attendance at formal services is at historically low levels, people are still looking for meaning and spirituality. Dudley Rose, Assistant Dean for Spiritual Research, noted that worldly places were surprisingly good at quenching that thirst.

“People met their spiritual needs in organizations that had no obvious spiritual connection,” Rose said in an interview. - For example, in SoulCycle. People will quote SoulCycle. "

Ter Kewle, Thurston, and Phillips see it this way: if it is part of a religious leader's job to find the suffering everywhere, then spiritual innovators need to go to their jobs.

“Whatever you or I may think about it, people still come to work with a huge emptiness inside, from a lack of belonging to something bigger and not connected to it,” said Thurston.

Maceo Paisley (left), an experienced designer, presents a prototype of an event mourning ritual at the Sacred Design Lab.

The Sacred Design Lab trio use the language of faith and the church to describe their work. They talk about organized religion as a technology for delivering meaning.

“The question we ask is: How can we translate into modern language ancient traditions that gave people access to practices that brought meaning to their lives in a context not centered around congregations?” Said ter Kyul.

Members of the nonprofit say they have pondered the design of rites for companies such as Pinterest, IDEO, and the Obama Foundation.

Philips does not believe corporations will replace organized religion - but she sees new opportunities for companies to give people the meaning they used to get from churches, temples, mosques, and the like.

She talks about her work like a regular pastor. “We spend a lot of time monitoring and keeping company with our customers,” she said. - We listen to their stories. We want to understand their lives. We want to understand their passions and aspirations. "

Ivan Sharp, co-founder of Pinterest, hired the Sacred Design Lab to categorize core religious practices and figure out how to apply them in the office. The lab prepared a spreadsheet for him.

“We've brought together hundreds of practices from many different religions and cultures, placed them in a table and tried to categorize them by emotional states: which ones are related to feelings of happiness, which ones relate to anger, and we took into account various metadata,” Sharp said. ...

Having collected all the data, he spent a couple of days reading them. "It sounds obscenely primitive," he said, "but for me it really changed some aspects of religion."

Through this work, he realized how many useful tools already exist in old-fashioned things like the church of his childhood. “Some of the Protestant rituals I grew up with have real emotional benefits,” he said. And Sharpe saw that it was good.

"An office is still an office"

Naturally, there are dangers in introducing elements of spirituality into the office.

The mixture of corporate and religious languages can be strange. For example, Ter Kul described his work for a technology company he didn’t want to mention: “We did research and wrote a concept paper, Spirit of Work, supporting bold ideas about how focusing on spirituality will be everything in the future. take root more strongly in the workplace. "

Another problem is related to the fact that many workers already profess some kind of religion on their own terms and in their personal time, and are not at all eager to engage in spiritual practices from 9 to 17.

Angie Thurston, co-founder of Sacred Design Lab: "People still come to work with a huge emptiness inside, from a lack of belonging to something bigger and not connected to it."

It is also difficult to convince workers of the transcendental value of their work if they can be fired. “It can be done badly, and then there will only be harm,” said Thurston. "For example, how can we build a deeply connected community if I can fire you?"

Thurston listed a set of possible challenges to deal with: creating a working religion, a mixture of management and soul seeking, getting money for spirituality. “Even if you do it right, and the workflow starts to revolve around the soul, the office is still an office,” said Thurston. "These are our problems."

Companies hiring ritual consultants may feel that they are giving workers a small bonus. However, the participants in the movement themselves hope to launch a revolution.

In recent years, workers have made significant strides in pushing employers to tackle systemic racism - for example, some companies have made June 19, Liberation Day in the United States, a paid day off, and are also investing in businesses owned by blacks or other minorities. Therefore, spirituality counselors wonder if workers might also begin to demand righteousness from employers as well.

This opportunity attracted Bob Boystour to work as a spiritual consultant. He is the director of the Fetzer Institute, a Michigan-based nonprofit foundation whose mission is to "help build the spiritual foundations of a world of love." The foundation has invested in the founding of the Sacred Design Lab. Boystour says he hopes the group's work will help corporate workers to voice their grievances and stop engaging in immoral projects or practices, even if they are profitable.

“Today we are looking at business profits: the deeper question, however, is whether business ennobles or degrades human existence,” Boystur said. "We urge employees to take moral considerations into account when discussing business issues."

Counselors find the rituals and language of religion and extract them from the religious context to - in theory - help workers cope with feelings of alienation. But rituals without religions can do things too.

Tara Isabella Burton, author of Strange Rituals: The New Religions of a Godless World , calls it tailor-made religions, or ritual splitting, much like the way cable TV packages began to split after the advent of streaming services. In a split world, people take what they like from different religions and include it in their lives - there is a bit of Buddhism, there is a bit of Kabbalah. It turns out consumer religiosity.

“You can decide that what we want, what feels right for us, what we desire — it all defines us personally, not the community,” Burton said. "We run the risk of translating spirituality into the category of a consumer product, something that is necessary personally for us or our brand."

Deepening Zoom Practices

If you work from home and stand in front of your computer, having one meeting after another, receiving and submitting projects, then you don't feel any difference. Physically, all these actions are the same.

I really want rituals. Every day I get dressed, put on my shoes, make coffee, pour myself a cup, and inform two of my flatmates that I’m going to work and see them later. Then I make a few circles around the apartment and sit at a table in the corner of the living room, just a couple of feet away. This is my strange coronavirus journey to work, and this is how I inform my emaciated mind that the work day has begun.

If my boss told me that we would have every night of breathing exercises to mark the closure of our laptops, or start each meeting with a clove scent, would I like that? I think yes.

It's easy to overlook the difference between routine and ritual. For example, what category would you put the habit of taking a shower and staring at the ceiling for five minutes after completing the main task of the day? And does this label matter if this action seems necessary?

But for the sake of accuracy, Kathleen McTeague, the priest of Unitarian universalism, the mentor of ter Kyula, offers her definition. She describes rituals as sublime practices with a purpose, attention and the need for repetition.

Kursat Ozenk has a long history of corporate rituals as a product developer for software giant SAP. He wrote Rituals for Work last year , and is set to publish something like a sequel, Rituals for Virtual Meeting , in January . I called him for guidance on deepening my practices with Zoom.

Ozenk advised to include meaningful breaks in your routine. He suggested starting videoconferences with a minute of silence. He recently learned about a sniffing ritual whereby each of the participants in a meeting pulls out the same spice, such as cinnamon, and everyone sniffs it at the same time to experience a joint sensory experience. He hopes to include this unifying practice in his councils.

“In the physical world, we experience the same sensations together - the same temperature, the same smell of warming up food,” Ozenk said.

Sue Philips, co-founder of the Sacred Design Lab, talks about her work like a typical pastor

. Phillips has other ideas as well. She suggests using a repetitive meeting structure to reassure the participants. This can be achieved by starting meetings with the same words, a kind of corporate spell.

Another idea is for each employee to light a candle at the beginning of the meeting, or they all pick up the same objects that are found in everyone's house.

Glenn Fajardo, professor at the Stanford School of Design, an explorer of rituals for virtual work, said the workday is a bit like a movie, with its structure, editing, and pumping around predictable story arcs.

“Tell your group to have everyone turn off the video during this discussion period,” Fajardo said. "Or, during this lesson, please look at your notebook."

"Part of the purpose of the ritual is to create these fragments that people can remember, these elements made up of something familiar and something new."

Jeffrey D. Lee, Bishop of the Diocese of Chicago, helped organize a three-day seminar last year with ter Kyul and others. It was held to get spiritual entrepreneurs to discuss ideas with leaders of traditional religions. He described one of the participants as "an experienced designer creating powerful rituals for CEOs."

Bishop Lee said he liked this use of religion, even if it happens in places where the ultimate calling is profit. "We are well aware that we exist in a period of historical decline of religions," he said, "so these events are good news for people eager to find rituals for themselves."