Introduction

This article is intended for those who are familiar with such a concept as ontology at least at an initial level. If you are not familiar with ontologies, then, most likely, the purpose of ontologies and this article in particular will not be clear to you. I advise you to familiarize yourself with this phenomenon before you start reading this article (perhaps even an article from Wikipedia will be enough).

So Ontology is a detailed characteristic of a certain subject area under consideration. This description should be given in some clearly formulated language. To describe ontologies, you can use the IDEF5 methodology, which has 2 languages in its arsenal:

- Schematic language IDEF5. This language is visual and uses graphic elements.

- Text language IDEF5. This language is presented in the form of structured text.

This article will consider the first option - a schematic language. We will talk about text in the following articles.

Objects

In the schematic language, as already mentioned, graphic elements are used. First, you should consider the main elements of this language.

Often, in ontology, both generalized entities and specific objects are used. Generic entities are called views . They are depicted as a circle with a label (name of the object) inside:

Species are a collection of individual specimens of a given species. That is, a view such as "Cars" can represent a whole collection of individual cars.

As instancesthis type can be specific cars, or certain types of equipment, or individual brands. It all depends on the context, subject area and its level of detail. For example, specific cars as physical entities will be important for a car repair shop. To maintain some statistics on sales in a car dealership, specific models will be important, etc.

Individual instances of views are designated similarly to the views themselves, only indicated by a dot at the bottom of the circle:

Also, in the discussion of objects, it is worth mentioning such objects as processes .

If views and instances are so-called static objects (not changing over time), then processes are dynamic objects. This means that these objects exist in a certain strictly defined period of time.

For example, you can single out such an object as the process of making a car (since we are talking about them). It is intuitively clear that this object exists only during the production of this very car itself (strictly defined period of time). It should be borne in mind that this definition is conditional, because such objects as a car also have their own service life, shelf life, existence, etc. However, we will not go into philosophy, and within the framework of most subject areas, it can be assumed that instances, and even more so species, exist forever.

Processes are depicted as a rectangle with a label (name) of the process:

Processes are used in the schemes of transition from one object to another. More on this later.

In addition to processes, such schemes uselogical operators . Everything is simple enough for those familiar with predicates, Boolean algebra, or programming. There are three main logical operators used in IDEF5:

- logical AND (AND);

- logical OR (OR);

- exclusive OR (XOR).

The IDEF5 standard (http://idef.ru/documents/Idef5.pdf - most of the information from this source) defines the image of logical operators in the form of small circles (compared to views and instances) with a label in the form of symbols. However, in the developed graphical environment IDEF5, we deviated from this rule for many reasons. One of them is the difficult identification of these operators. Therefore, we use a textual designation of operators with an identification number:

Let's finish with the objects at this point.

Relations

There are relations between objects, which in ontology mean the rules that determine the interaction between objects and from which new conclusions are drawn.

Typically, relationships are determined by the type of schema used in the ontology. A schema is a collection of ontology objects and relationships between them. There are the following main types of schemes:

- Composition schemes.

- Classification schemes.

- Transition schemes.

- Functional diagrams.

- Combined schemes.

Also, sometimes this type of scheme is distinguished as existential . An existential schema is a collection of objects without relationships. Such schemes simply show that a certain set of objects exists in a certain subject area.

Well, now, in order about each of the types of schemes.

Composition schemes

This type of schema is used to represent the composition of an object, system, structure, etc. A typical example is car parts. In the most enlarged composition, the car consists of a body and a transmission. In turn, the body is divided into a frame, doors and other parts. This decomposition can be continued further - it all depends on the required level of detail in this particular task. An example of such a scheme:

Composition relations are displayed as an arrow with a tip at the end (as opposed to, for example, a classification relationship, where the tip is at the beginning of the arrow, more details below). Such relationships can be signed with a label as in the picture (part).

Classification schemes

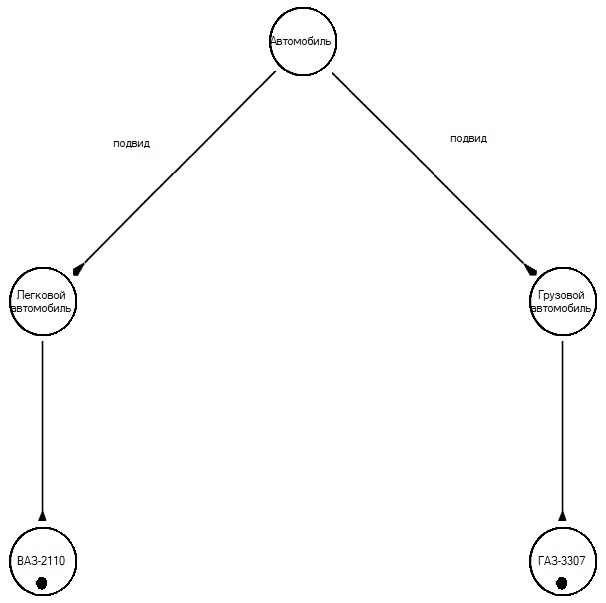

Classification schemes are designed to express the definition of species, their subspecies, and species specimens. For example, cars can be cars and trucks. That is, the "Car" view has two subspecies. VAZ-2110 is a specific instance of the "Passenger car" subspecies, and GAZ-3307 is an instance of the "Truck" subspecies:

Relationships in classification schemes (subspecies or a specific instance) have the form of an arrow with a tip at the beginning and, as in the case of schemes compositions can have a label with the name of the relationship.

Transition schemes

Diagrams of this type are necessary to display the processes of transition of objects from one state to another under the influence of a certain process. For example, after the process of painting with red paint, a black car turns red:

The transition ratio is indicated by an arrow with a tip at the end and a circle in the center. As you can see from the diagram, processes are related to relationships, not objects.

In addition to the ordinary transition shown in the figure, there is a strict transition. It is used in cases where the transition in a given situation is not obvious, but it is important for us to emphasize it. For example, installing a rearview mirror on a car is not a significant operation if we consider the process of assembling a car globally. However, in some cases it is necessary to highlight this operation:

A strict transition is indicated in the same way as a normal transition, except for a double tip at the end.

Regular and strict transitions can also be marked as instant. To do this, a triangle is added to the central circle. Instant transitions are used in cases where the transition time is so short that it is completely insignificant within the considered subject area (less than the minimum significant time interval).

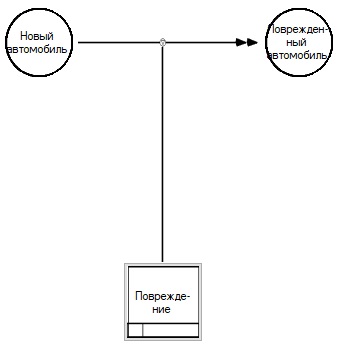

For example, with even the slightest damage to the car, it can be considered damaged and its price drops sharply. However, most damage occurs instantaneously, as opposed to aging and wear:

The example shows a strict transition, but a normal transition can also be used as instantaneous.

Functional diagrams

Such schemes are used to indicate the structure of interaction between objects. For example, a car mechanic performs maintenance on cars, and a car service manager accepts requests for repairs and hands them over to a car mechanic:

Functional relationships are depicted as a straight line without a tip, but sometimes with a label, which is the name of the relationship.

Combined schemes

Combined schemes are a combination of previously discussed schemes. Most of the schemas in the IDEF5 methodology are combined, since there are rarely ontologies that use only one type of schema.

Boolean operators are often used in all schemes. By using them, you can implement relationships between three, four or more objects. The logical operator can express some general entity over which the process is carried out or which participates in another relation. For example, you can combine the previous examples into one like this:

In a specific case, the combined scheme uses a composition scheme (mirror + a car without a mirror = a car with a mirror) and a transition scheme (a car with a mirror becomes a red car under the influence of the red paint process). Moreover, a car with a mirror is not expressed explicitly - instead, the logical operator AND is indicated.

Conclusion

In this article, I have tried to describe the main objects and relationships in the IDEF5 methodology. I used the automotive domain as an example, as it turned out to be much easier to build diagrams. However, IDEF5 schemas can be used in any other area of expertise.

Ontologies and domain knowledge analysis is a rather extensive and laborious topic. However, within the framework of IDEF5, everything turns out to be not so difficult, at least, the basics of this topic are learned quite easily. The purpose of my article is to attract a new audience to the problem of knowledge analysis, albeit at the expense of such a primitive IDEF5 tool as a graphic language.

The problem of the graphic language is that it cannot be used to clearly formulate some relations (axioms) of the ontology. There is IDEF5 text language for this. However, at the initial stage, the graphical language can be very useful for formulating the initial requirements for an ontology and defining a vector for the development of a more detailed ontology in the IDEF5 text language or in any other tool.

I hope this article will be useful for beginners in this field, maybe even for those who have been dealing with the issue of ontological analysis for a long time. All the main material of this article has been translated and meaningful was borrowed from the IDEF5 standard, which I referred to earlier ( duplicate ). Also inspired by a wonderful book from the authors from KNOW INTUIT ( link to their book ).