The Galaksija computer was a hobby of many people in Yugoslavia in the 1980s, who created their own devices literally on their knees. The idea behind it all was simple - to make technology available to everyone. How this idea was born and what came of it, says Cloud4Y.

Technologies in the SFRY

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was a political anomaly. She was recognized by the USSR as a socialist state and participated in the work of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, but kept aloof. Along with Egypt, Ghana, India and Indonesia, the “Non-Aligned Movement” was created in the country, promoting the principle of non-participation in military blocs.

Having chosen an individual path of development, Yugoslavia was forced to cope with many problems on its own, including logistical ones. The defense industry developed during the war and many industrial enterprises needed orders, as well as effective production and supply management. This need has given impetus to the development of the local computer industry. Raiko Tomovich

made a significant contribution to this process, a Yugoslav robotics engineer who was also directly involved in the invention of the world's first artificial hand with five fingers. Together with a team of mathematicians and mechanical engineers, he worked at the Mihajlo Pupin Belgrade Institute for Telecommunications and Electronics, developing equipment manufacturing technologies using “local” tools and parts. The rise in living standards during the 1960s and 1970s led to the need for more and more widespread use of computers (in accounting, government, etc.). Yugoslavian computer culture, albeit peculiar, flourished thanks to intensive government support.

Computers were expensive back then. The average price of Iskradata 1680, Sinclair ZX81 or Commodore 64, standard consumer-grade machines installed in government offices, accounting firms and scientific laboratories, was many times higher than the monthly salary of the average Yugoslav worker. Hindered and severe restrictions imposed by the country on the import of any product worth more than 50 German marks. This amount was significantly lower than what was required to purchase the purchase of an 8-bit microcomputer made outside of Yugoslavia.

As a result, it turned out that the study of computer technology, experiments and programming in the 1970s were available only to educated and wealthy Yugoslavs. As a rule, these were members of popular art, musical and literary movements, such as New Trends, Novi Val (New Wave).

Birth of an idea

Nevertheless, there were also self-taught people who, on their own, moved the computerization of the country forward. One of them was Voja Antonich, a fan of radio engineering and computer electronics . Note that Antonich by this time was already a famous engineer. He developed Arbitar, the official timing system used at several Balkan ski competitions, as well as an interface for transferring frames from monochrome monitors to 16mm film.

While on vacation in Montenegro, Antonich studied the documentation for the new line of single-chip CDP1802 processors and thought about the possibility of imaging by means of the central processor. Although the CDP1802 was too primitive for this, the capabilities of the Zilog Z80 seemed to be enough for this.

This gave him an idea. Rather than using a complicated and expensive video controller, Antonić decided to explore the possibility of creating a computer whose 64x48 block graphics were entirely generated using only the cheap Zilog Z80A microprocessor - a processor that can be easily purchased from electronics stores throughout Yugoslavia. When he returned to Belgrade, Voya already had a conceptual diagram of a computer, the processor of which controls the generation of the image. Of course, this approach greatly reduced the productivity of the machine, but in theory it greatly simplified the circuit and reduced cost.

Back home, Antonich tested his idea and found it worked! The effect of his intervention was striking: he brought down the total cost of the computer and optimized its design. However, more importantly, the scheme was so simple that users could assemble the computer themselves. Antonich's longstanding commitment to open source hardware and software allowed his invention to spread across the country.

Popular recognition

While Antonić was busy with his computer, journalist and programmer Dejan Ristanović wrote a positive article about computer technology for the Yugoslav popular science magazine Galaxia. Soon after the publication of this article, the editor-in-chief of "Galaxy" Yova Regasek received an unusual letter. In it, the reader asked to devote the next issue of the magazine to computers.

The idea was skeptical, but Regasek instructed Ristanovich to lead this project. And the two enthusiasts found each other. Antonich was just looking for a place to publish schemes for his new "people's computer". He had options with Elektor from Germany and BYTE from the USA, but these magazines were expensive and the availability of the idea was a priority. The obvious choice was SAM magazine published in Zagreb, but there was a bad experience with it. Therefore, when a mutual friend brought Ristanovich and Antonich together, they quickly agreed on everything. The project found its home in Galaxia.

Jova Regasek (left) and Voya Antonic assembling a prototype

A special 100-page issue of Computers in Your Home (Računari u vašoj kuć) was released in December 1983 (although it was dated January 1984). Most of it was devoted to Antonich's computer: it included not only diagrams, but also detailed instructions for assembling the circuit, storage locations for purchasing homemade equipment, mail-order addresses for receiving built-in kits, and channels through which it was possible to legally order accessories from - abroad. Yugoslavian computer enthusiasts decided to name the project after the magazine, and no one even thought that the readership on this issue would exceed the usual circulation of "Galaxy". According to Dejan Ristanovich, the circulation of 30,000 copies was sold out in a few weeks, and it had to be reprinted four times (!).

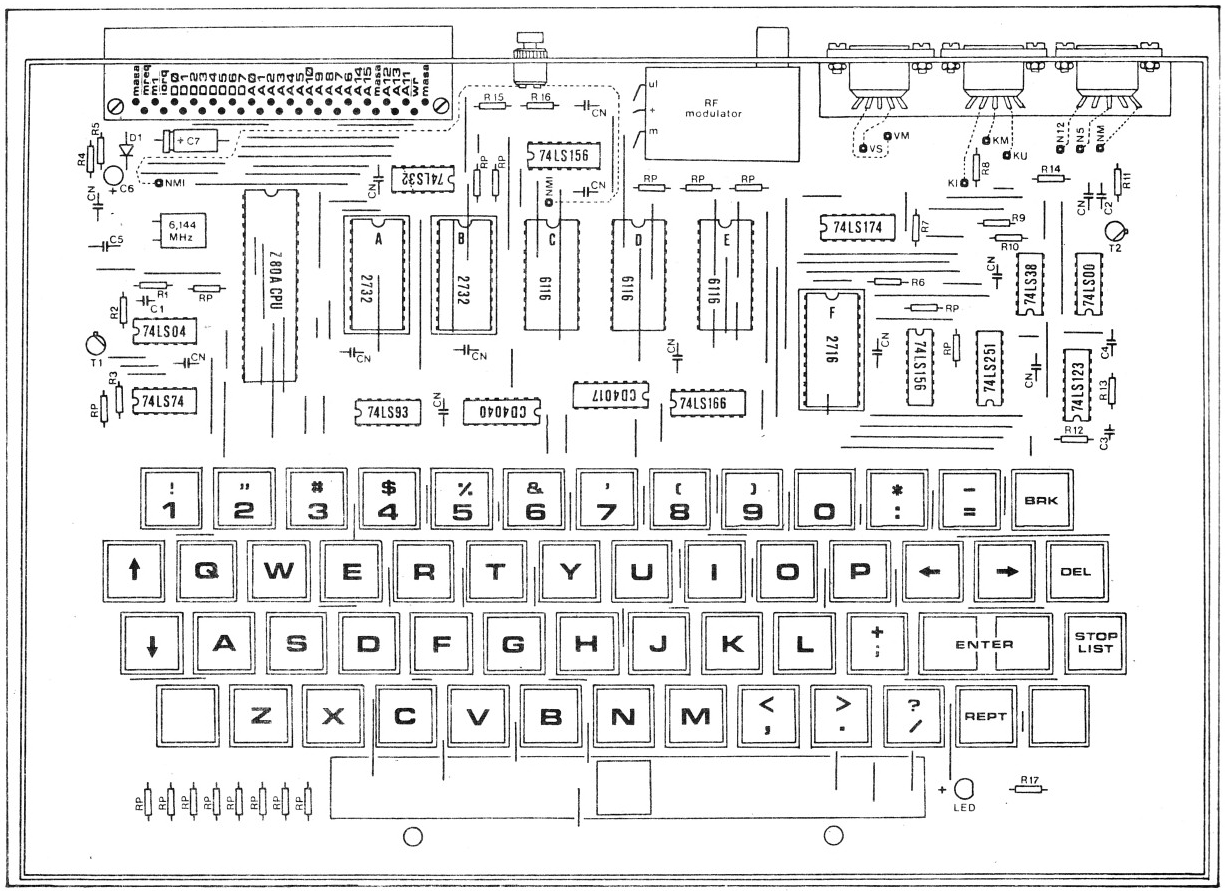

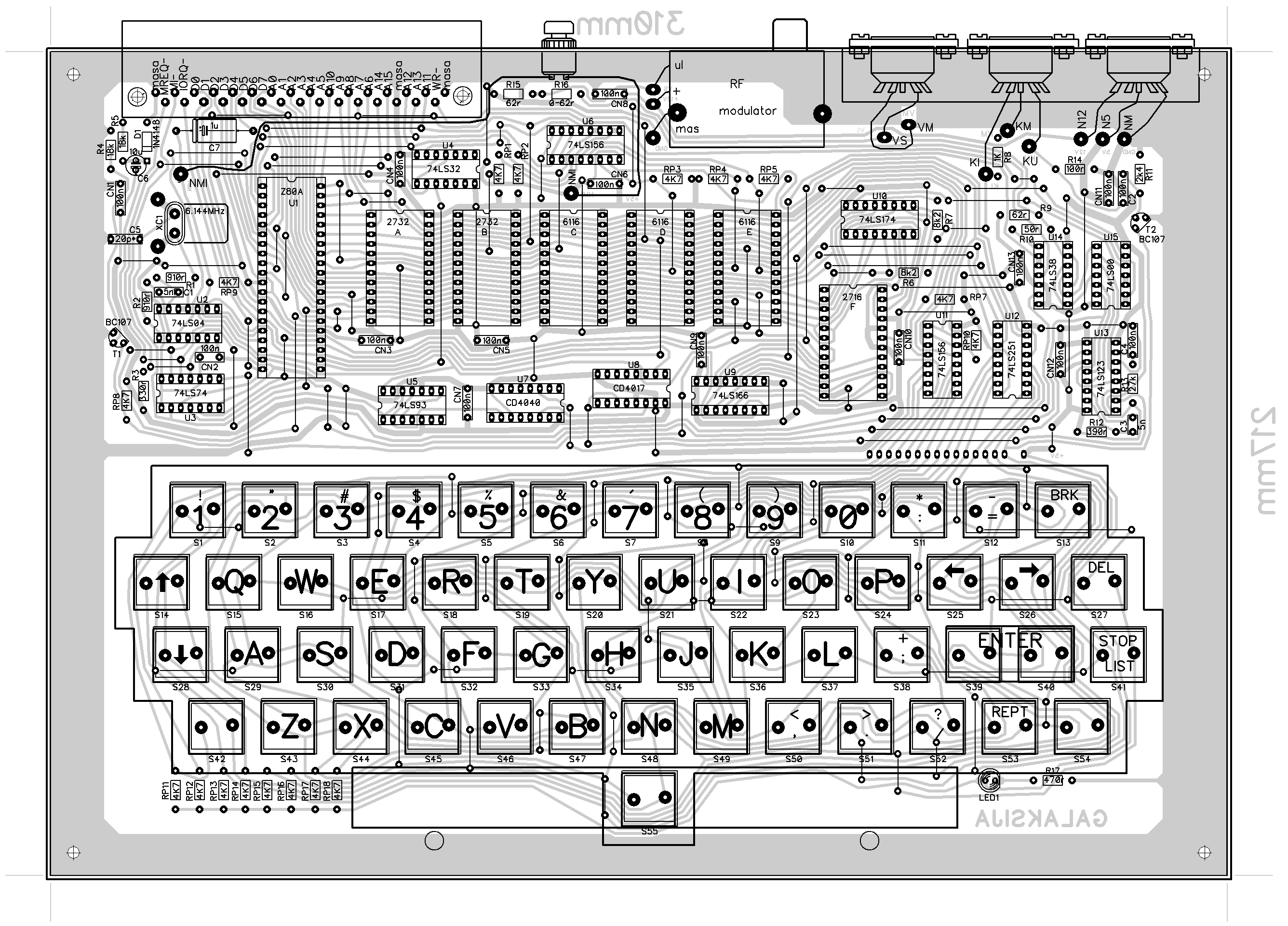

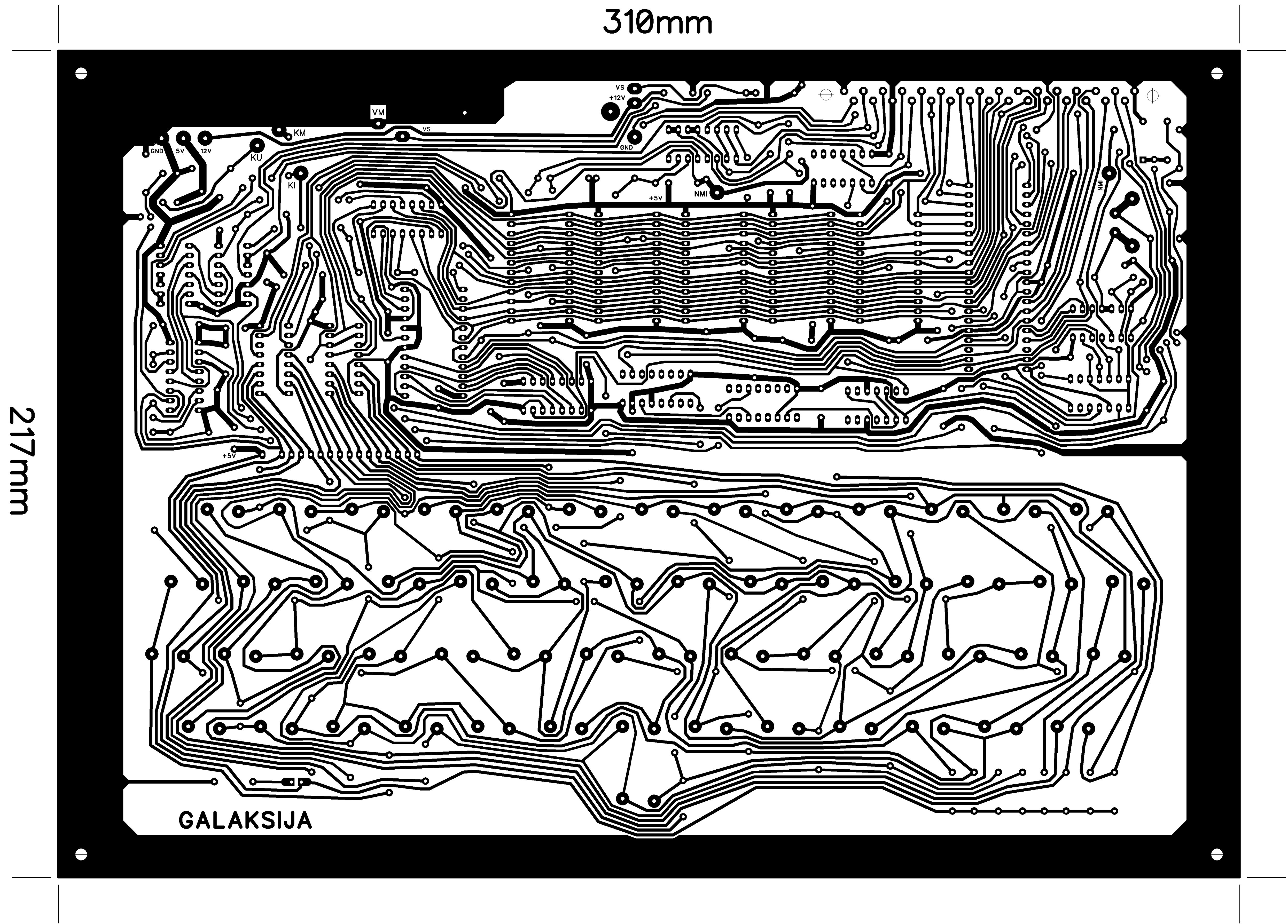

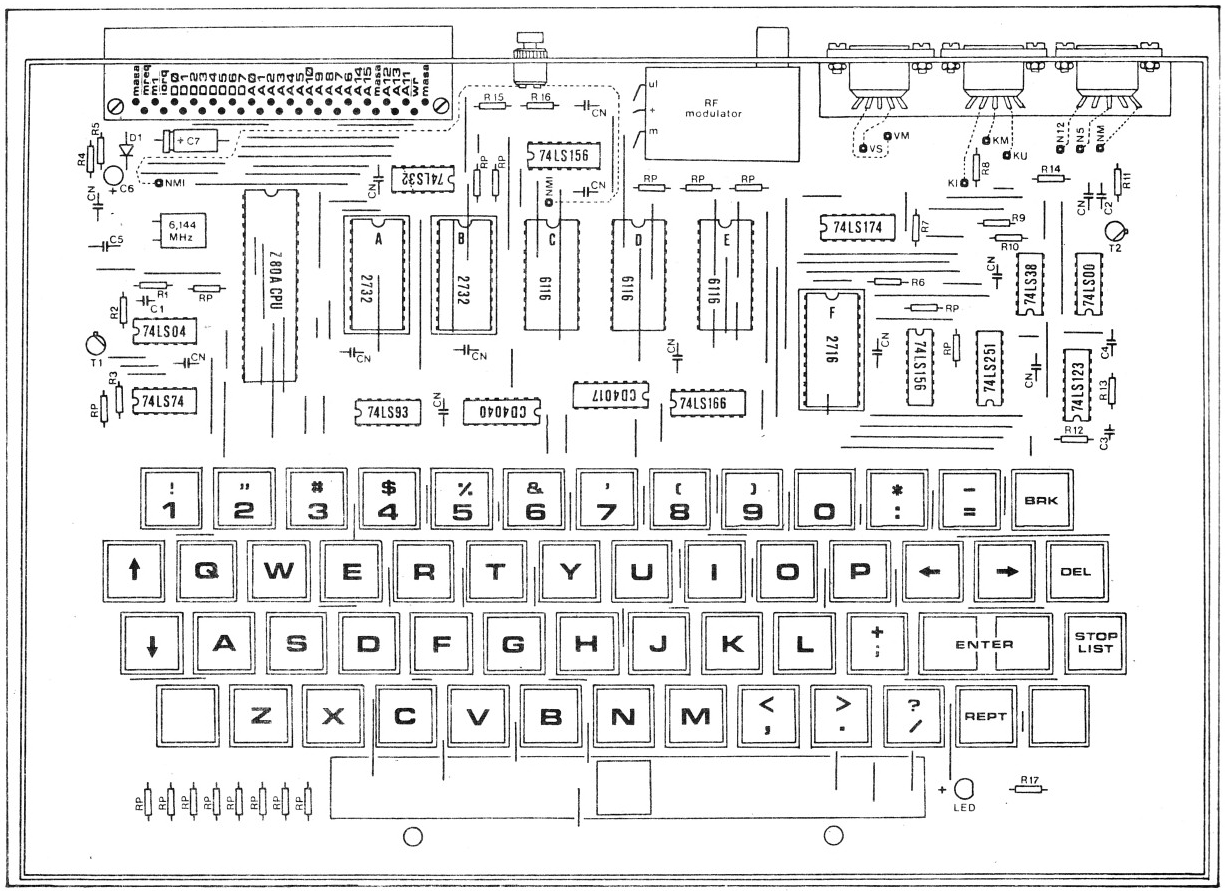

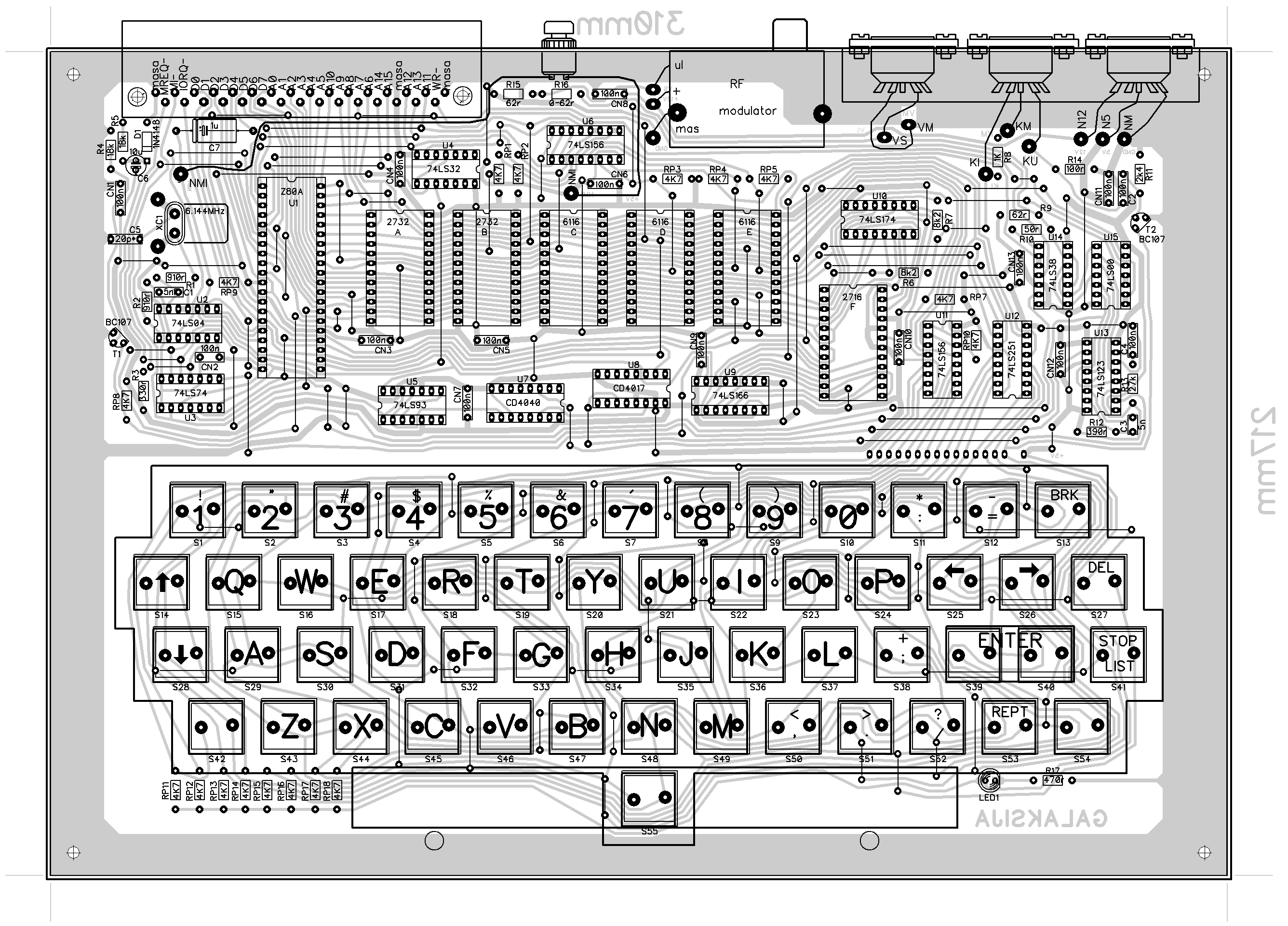

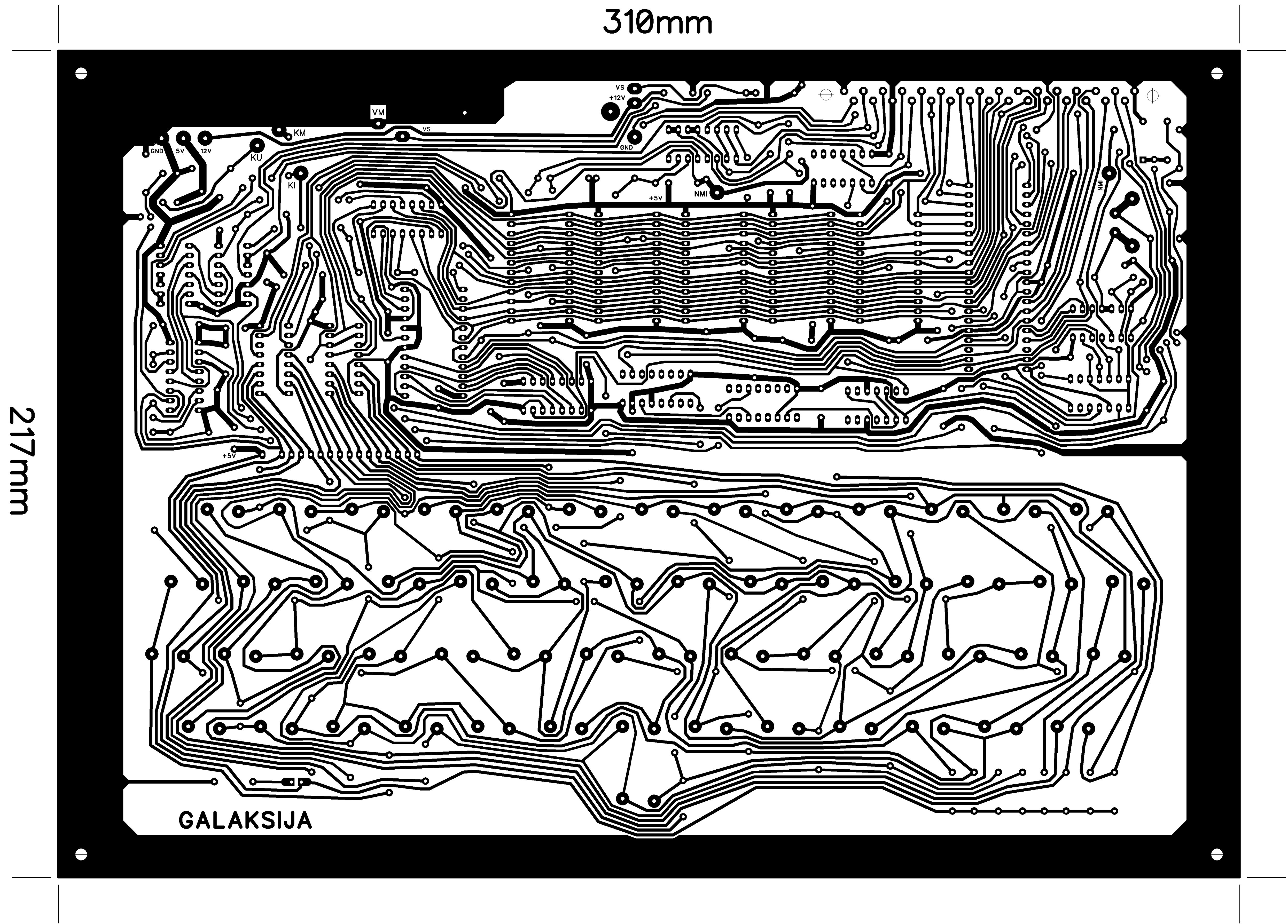

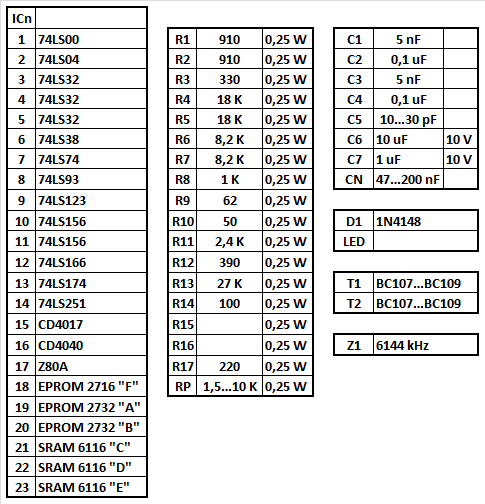

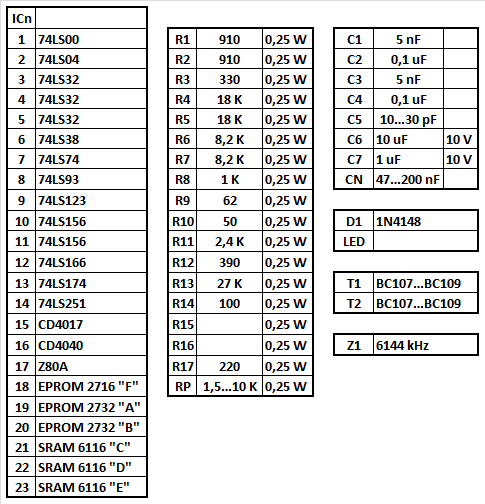

PCB wiring diagram

Voya Antonich recalled that the day before the issue was published, he, together with Dejan Ristanovic and Jova Regasek, tried to guess how many readers would try to create Galaxia. Sounded options from 50 to a thousand people. They found out more or less the correct answer when they released 120,000 copies of the magazine. The editorial office received over 8000 letters from readers who created their own computer. There could be more, as Galaksija was distributed in the form of a do-it-yourself kit, but it could have been assembled entirely on your own. Many enthusiasts did not order printed circuit boards or flash ROMs, obtaining these components themselves. Later, the computer was also offered fully assembled. The price of the assembly kit in the minimum configuration (only ROM A, 4 KB of RAM) in 1984 was 45,500 dinars (181 Soviet rubles).

Pages of the very same magazine

The components of the assembly kit were produced and supplied from various sources: MIPRO and Elektronika, together with the Institute of Electronics and Vacuum Technology, supplied printed circuit boards and keyboards; Mikrotehnika (Graz) - integrated circuits. Voya Antonich personally flashed all the ROMs, the staff of the editorial staff of the magazine "Galaxy" prepared printed materials and organized mailing to customers. Later, the institute responsible for the preparation of school textbooks and manuals, together with Elektronika Inženjering, began mass production of Galaksija computers for delivery to schools.

What was the computer

The technological limitations of the device helped him manifest his amazing capabilities. Antonich's microcomputer contained only 4 KB of program memory - sheer nonsense compared to any modern laptop. Because of this limitation, the system was only able to display three single word error messages: users were getting "WHAT?" if their main code had a syntax error, "HOW?" - if their requested input was not recognized, and "SORRY" if the machine has exceeded its memory capacity. The 4K EPROM - Erasable Programmable ROM - was packed so tightly that some of the data bytes were used for different purposes. With this solution, Antonich's firmware serves as proof that more than 100% of the program memory can be used.

Inside Galaxia

The insides of the car reflected the environment in which it thrived. No two Galaxias were alike. In addition to the design features that always accompany the kits assembled for trial, and even newbies, the device was delivered without a case. This oversight has fueled the creativity of computer enthusiasts. Many have created their own bodies.

Like other computers of the time, the Galaxy Cassette Port was the primary storage system. While most other computers would automatically launch the program after loading the tape (this was a primitive copy protection), Antonich's commitment to open source software played a role. After downloading the program, users had to enter the "RUN" command to make it work. This extra step, however simple, worked as a deterrent for programmers to impose some kind of copy protection on their work. The feed could be easily entered, edited, or copied in bulk. The idea of free hardware and software was strongly encouraged: sharing, collaborating, and distributing software was integrated into the very raison d'être of Galaxy.

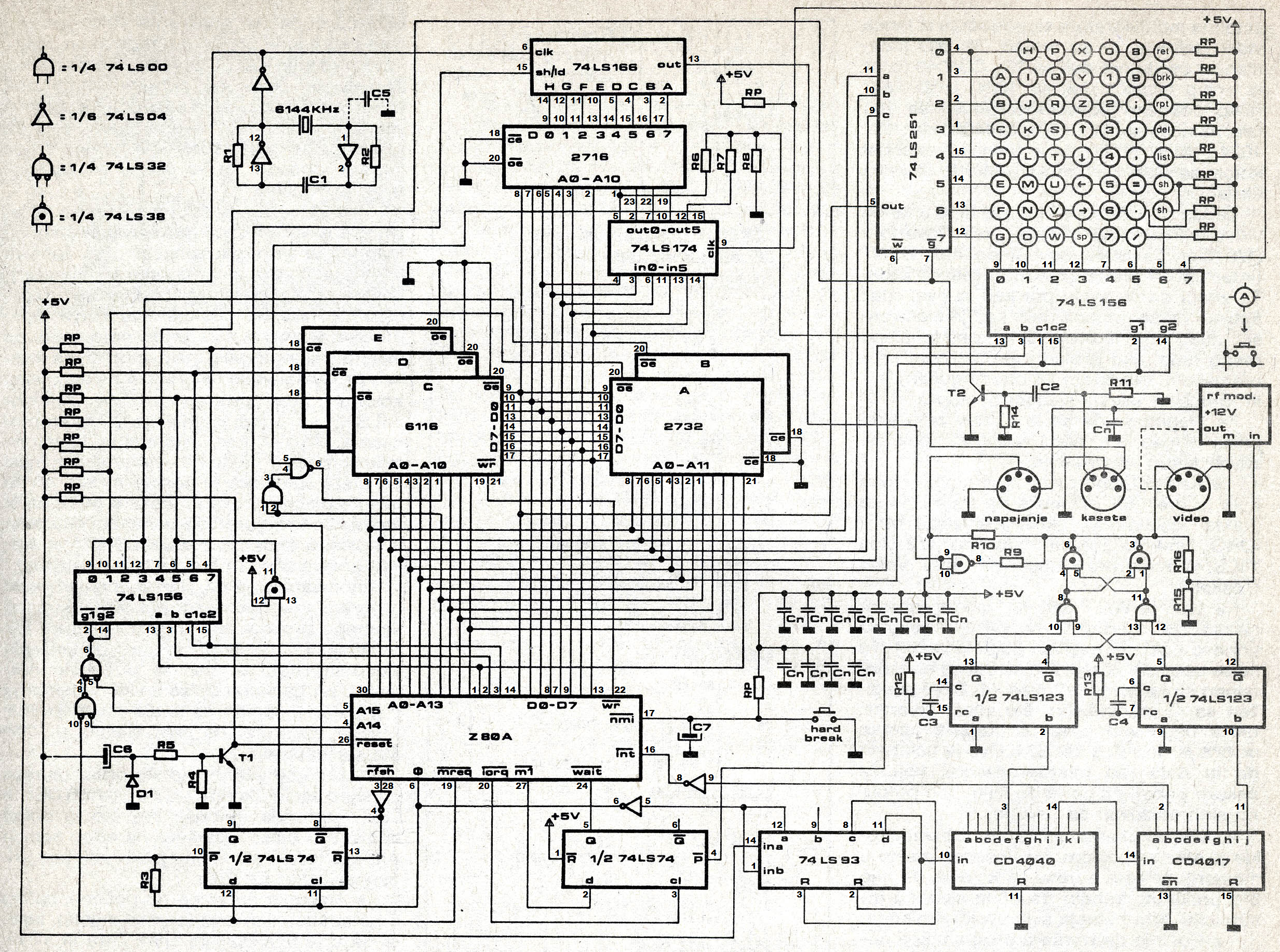

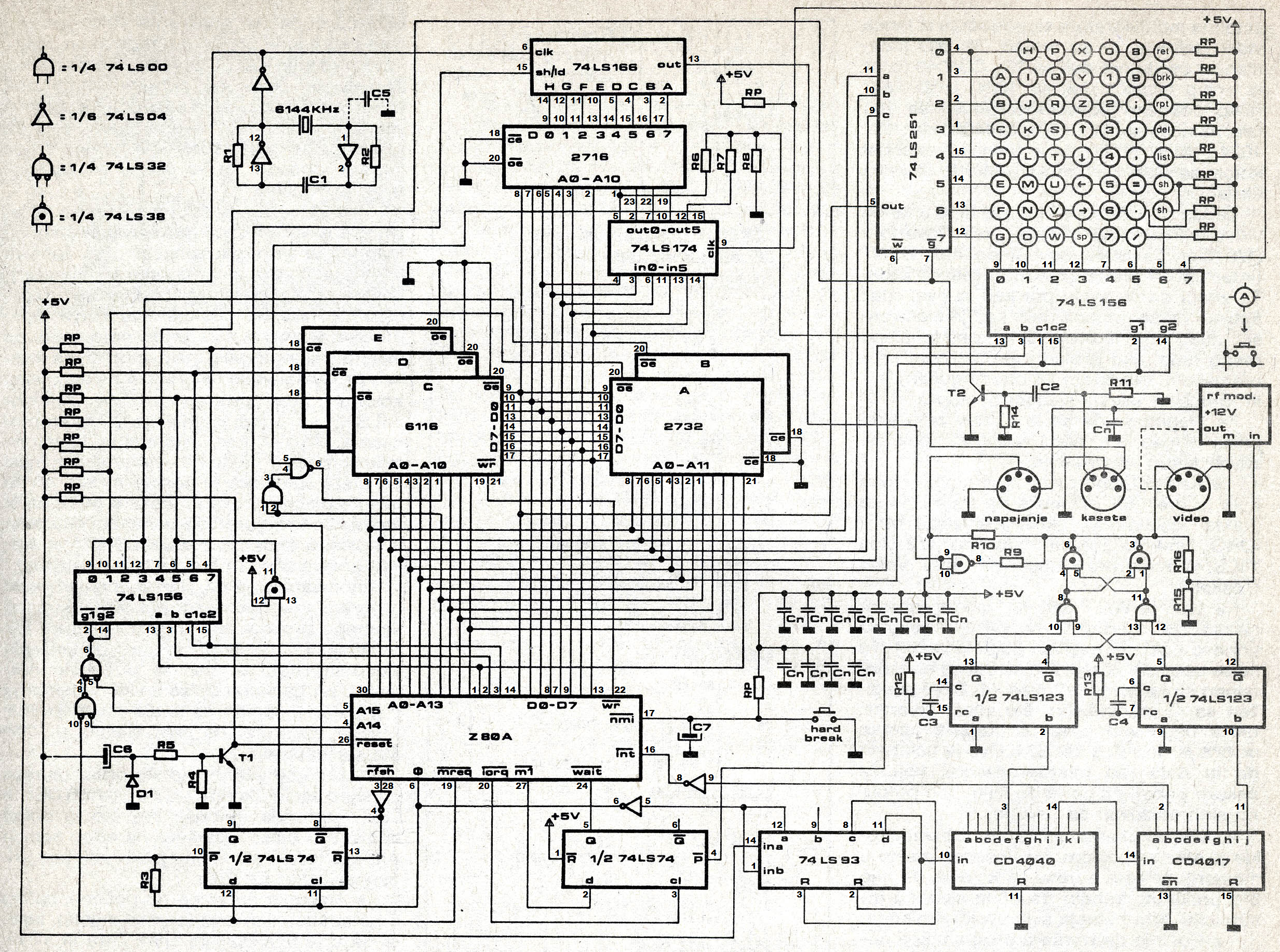

Galaxia schematic

Galaxy did not have a separate chipset for shaping the video signal; instead, most of the work of shaping the video signal was taken over by the central processor using a separate shift register. At the beginning of the 57th line of the half-frame, an interrupt was triggered, during which the processor formed 208 image lines. 512 bytes of RAM was used to store the characters that make up the current screen. The processor took the next 8-pixel character string from the character generator and passed it to the shift register, which, in turn, gave this byte bit by bit to the video output.

About two-thirds of the CPU time was used to form the image, which, of course, affected the speed of the machine. When writing and reading data from a cassette, the video output was disabled. BASIC also had the ability to turn off the image to work in "fast" mode.

Since the video signal was generated by software, it was possible to take over the formation of the image, and some programs used this opportunity, for example, to output characters from their own character generator. Having enough memory, even without hardware alterations, it was possible to display graphics of a higher resolution - up to 256 × 208 pixels - this required 6144 bytes for video memory.

But this was the graphics

The cassette input was fairly simple and used only a few elements to control the input level. The resulting 1-bit signal was fed to the same microcircuit that was responsible for the keyboard, so at the software level the tape input looked like a sequence of quick keystrokes / releases. Initially, the computer was not supposed to produce sound, so most programs did not count on this. However, the tape output port could be used as a 1-bit speaker output.

Specifications

- Central processing unit: Zilog Z80A @ 3.072 MHz

- Memory: from an addressable space of 64 KB, the first 8 KB are allocated for ROM, the rest for RAM

- Video mode: text only, 32x16 characters, monochrome

- Pseudo-graphics: 2x3 dots per character, 64x48 dots total

- Keyboard: 54 keys

- Sound: not in the original specification, but can be received through the tape output

- Storage device: consumer cassette recorder, recording speed 280 bps

- Interfaces: system port , 44 pins; Tape recorder port - DIN connector; Video output in PAL format - DIN connector, black-and-white video signal; High-frequency video output - RCA connector

What else is Galaxia remembered for

Computer enthusiast Zoran Modli also learned about the new computer from the magazine. Zoran was the host and DJ of Ventilator 202, the famous New Wave radio show on Serbian radio. We can say that Modley was something of a small celebrity in his country.

At that time, cassettes began to gradually replace vinyl records. Portable players like the Sony Walkman have been on the rise. Sensing the potential of this niche, in the fall of 1983, Jova Regasek called Modli with a proposal for a radical new broadcast format. The idea was this: since all computers, including Galaxia, ran their programs on cassette, Modley could broadcast the programs on the radio as sound during his show. Listeners could record programs from their receivers as they were broadcast and then download them to their computers.

This practice became a real sensation, increasing the popularity of Modli's show. In the months that followed, the Ventilator 202 broadcast hundreds of computer programs. For an hour before the start of the broadcast, Modley warned listeners that it was time for them to take the equipment and prepare for the recording. Fans of the show also began recording their programs and sending them to the studio so that others could use their work. These programs included audio and video recordings as well as magazines, concert listings, party promotions, tutorials, flight simulators, and adventure games.

In the case of games, users could download programs from the radio, change them by adding new levels / tasks / characters, and then send them to Modly's show for re-transmission. In fact, it was its own way of transferring files, used long before the advent of the World Wide Web.

How did it end

In the mid-1980s, Yugoslavia entered a period of deep political and social uncertainty. Several bloody wars and a downturn in the economy put an end to cultural and computer development. By then, restrictions on imports and tariffs had been eased, and Western computers had been adopted in the country by consumers, corporations and government agencies alike.

Within a short time, ready-made Galaxias were sent en masse to some Yugoslav high schools and universities. The further development of the line continued with the appearance of 5 functional prototypes, however, due to their already moral and technical obsolescence, work on them ceased in 1995. Antonich himself threw away all five of his personal prototypes of Galaxia, which he greatly regretted. However, later, one surviving prototype was found in the cellar of the Antonić house, which was transferred to the Museum of Science and Technology in Belgrade.

Although Galaksija is not comparable in its capabilities to commercial computers of the same time, it had an important local influence. Many enthusiasts have studied the work of computers using this example - it turned out to be a good tool for learning and experimenting.

Besides, the idea was important. Antonich showed that computing should be cheap and accessible to everyone. And that alternative ways of development are possible, paths completely different from those of Western giants such as IBM, Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard or Apple. In this sense, Antonich's 1983 project was more than just a microcomputer.

What else is interesting in the Cloud4Y blog

→ The US State Department will create its own great firewall

→ Artificial intelligence sings about the revolution

→ What is the geometry of the Universe?

→ Easter eggs on topographic maps of Switzerland

→ Firebase again became the subject of research

Subscribe to our Telegram-channel so as not to miss another article. We write no more than twice a week and only on business.