Imagine that you are a resident of Ancient Rome in the first century BC. Your wife convinces you to buy a certain item. It's quite expensive, so you hesitate because you don't have much cash. One would imagine that such an excuse in those days would have allowed you to go unpunished. After all, what choice do you have: you can't write a check? Actually it is possible, as the poet Ovid writes in the book of the first " Science of Love ". And since your wife knows about this, you have no other choice:

“A woman will find a remedy for passionate men to rob.

Here the peddler came, laid out the goods in front of her,

She will review them and turn to you,

"Choose," she will say, "the taste, I will see how picky you are,"

And he will kiss later, and coo: "Buy!"

She will say that this is enough for her for many years, - They sell the necessary thing, how can you not buy it?

If the money, they say, is not with you - ask for a receipt,

And you will envy those who are not learned to write. "

(Translated by M.L. Gasparov.)

In Roman times, large sums of money changed owners. People bought real estate, traded and invested in the provinces taken over by the Roman legions. How did this happen? In his "Letters Fam., V, 6" and "Letters Att., XIII, 31" Cicero writes: "For 3,500,000 sesterces I bought the same house some time after your congratulations" and "the nearest neighbor is Guy Albanius; he bought a thousand yugers [625 acres] from Mark Pili, as I recall, for 11,500,000 sesterces. " "How?" - asks the historian Harris (in his book " The Nature of Roman Money "), - "How Cicero paid the three and a half million sesterces that he laid out for his famous house on the Palatine… This would require loading and moving three and a half tons of coins through the streets of Rome. When Gaius Albanius bought the estate from Mark Pilius for eleven and a half million sesterces, did he physically send him this amount in silver coins? "Harris responds this way: “Almost without the slightest doubt, at least most of the amount was transferred through documentary [i.e. paper] transactions. The most popular procedure for buying large property during this period is mentioned by Cicero [ On duties. Book II, 3.59 ] ... " nomina facit, negotium conficit " - granting credit [or "commitment" - nomina ] completes the purchase. "

Marcus Tullius Cicero

What is this nomina , from which, by the way, comes the concept of "nominal", usually used in economics? In his Ph.D. thesis " Bankers, Moneylenders, and Interest Rates in the Roman Republic " Charles Barlow writes (pp. 156-156): “The account was called a nomen . Initially, the word meant just that - a name with some numbers. By the time of Cicero ... [ n ] omen could also mean “debt” referring to the records in the accounts of the creditor and the debtor. " And this "debt was in fact the blood of the economy of Rome at all levels ... nominawere a perfectly standard part of the lives of property owners, and also a daily fact for a large number of other people ”(Harris, p. 184). Pliny the Younger , for example, wrote (in Letters): “Perhaps you will ask if I can get these three million without difficulty. Almost all my capital is invested in land, but I have money invested at interest, and I can borrow it to you without difficulty. "

Renovation of buildings on Palatine Hill

For the sake of concreteness, let's say that a friend Sempronius owes you one million sesterces. You yourself, or if you are a rich senator or equity , then your financial advisor ( procurator - for Cicero it was Titus Pomponius Atticus ) will write down the debt in the ledger. What if you need money to buy some property? Will you have to wait for Sempronius to bring you a bag of a million sesterces? No! Since Sempronius is a reliable creditor ( bonum nomen [see Barlow, p. 156]; in modern credit classification agency terminology, AAA creditor), you will do as Cicero described: pass nominaand close the deal. For example, Cicero writes to his financial advisor Atticus ( "Letters Att., XII, 31" ): "If I sold Faberius's bond, I would not hesitate to prepare even cash for the Silievs, if only I could persuade him to sell." Harris (p. 192) remarks: “ Nomina were circulating and by the second century BC, if not earlier, were habitually used as a means of payment for other assets ... In Latin, the procedure by which the payer transfers the nomen of what is owed to him, the seller, is called delegatio ".

So we realized that the Romans could do the calculations by transmitting nomina . But was there a market for nominaHow do mortgage-backed securities exist in the modern world? According to both Barlow and Harris, the answer is yes. They argue that the Romans took one step further towards convertibility and, in effect, transformed "plain ledger entries" into "negotiable bills" (see Barlow, p. 159, and Harris, p. 192). Not everyone agrees with this. The economic historian P. Temin (" Financial Intermediation in the Early Roman Empire ") also reports that there is evidence of the possibility of assignment of debts, which opens up opportunities for "wider negotiability." “But,” he adds, “we have no evidence that this happened” (p. 721). However, there is circumstantial evidence. For example, the meaning of negotiable bills seems to have been well understood by Roman jurists, in particularUlpianu ( Digest Justinian XXX.I.44 ): “The party transferring the bill transfers the debt claim, and not just the material on which it is written. The fact of the sale confirms that when the bill is sold, the debt is also sold, by which it is confirmed. "

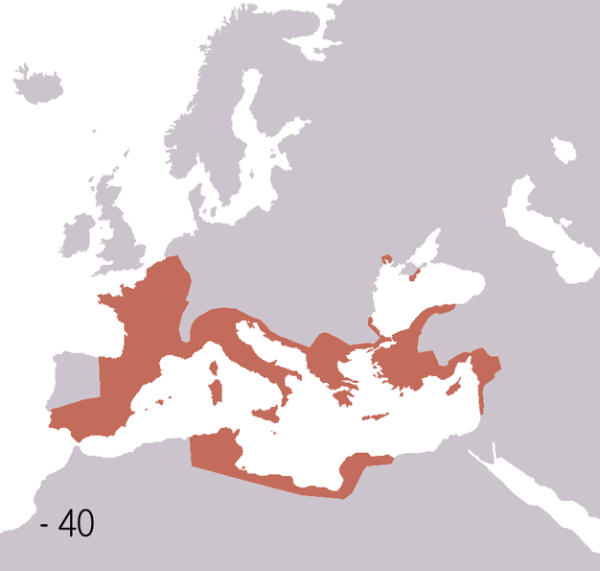

What if we need to transfer money to someone else in the world? When the dominions of

Rome expanded to Greece, Spain, North Africa and Asia, Rome's finances faced this logistical challenge. If you are in Rome and, for example, want to finance the Guy mines in North African Tapse, how can you transfer the money to him? He needs silver to buy materials, slaves and other goods, but you naturally really don't want to send money to Africa by sea - their chances of getting there are low (they are threatenedpirates , shipwrecks, etc.). “The remarkable contribution of Rome to the banking of antiquity was permutatio — the transfer of funds through paper transactions” (Barlow, p. 168). It worked in the following way: published were private companies collecting taxes in the provinces (as well as many other cases; see the article " Publicani " by Ulrik Malmendier). They had a branch in Rome and another in Tapse. Therefore, if you gave them silver in Rome (or gave them nomina), then they sent part of the taxes collected in North Africa to Guy. In exactly the same way, the Republic financed its public expenditures in the external territories. Since taxes were collected in all provinces, exchanging promissory notes for taxes, the Romans could transfer funds around the world - or at least over the part that ancient Rome captured.

Rome in 40 BC

It is curious that some historians measure the development of the financial system of Rome "by the degree of presence of banks" (Temin, p. 719). Of course, if we do not find evidence of the existence of our bank in the first century BC, this does not necessarily imply a lack of development. Before the Great Recession in the United States [2007-2009 financial downturn], most financial intermediation did not involve banks - it took place through the " shadow banking system ." The financial aristocracy of Rome "acted mainly through brokerage" (K. Verboven " Faeneratores, Negotiatores and Financial Intermediation in the Roman World", p. 12), and therefore a little reminiscent of the predecessor of the shadow banking system. Like the shadow banking system of the United States, it was fragile . Returning to our first example, it is worth noting that if someone who wants to buy a property begins to doubt the creditworthiness of Sempronius , it will not accept his payment in nomina and will demand cash. This will force you to demand the repayment of the debt from Sempronius, who in turn will have to demand repayment of the debt from Titus, etc. However, the financial crises of Ancient Rome is a topic for a separate article.

We express thanks to Cameron Hawkins of the University of Chicago for help in finding literature.