Thin threads stretch to my hands,

As if on stage without them I would stumble ...

Hey there, above, you let me go,

I can do without invisible threads ...

A. Zhigarev, S. Alikhanov "The Song of the Doll"

Hello, Habr! I am very glad that my strange articles, which I have combined with the title "New starting point", are interesting for someone to read. And I want to say thank you for that. Before that, I reasoned based on some famous films, but sometimes I want to reflect on a free flight.

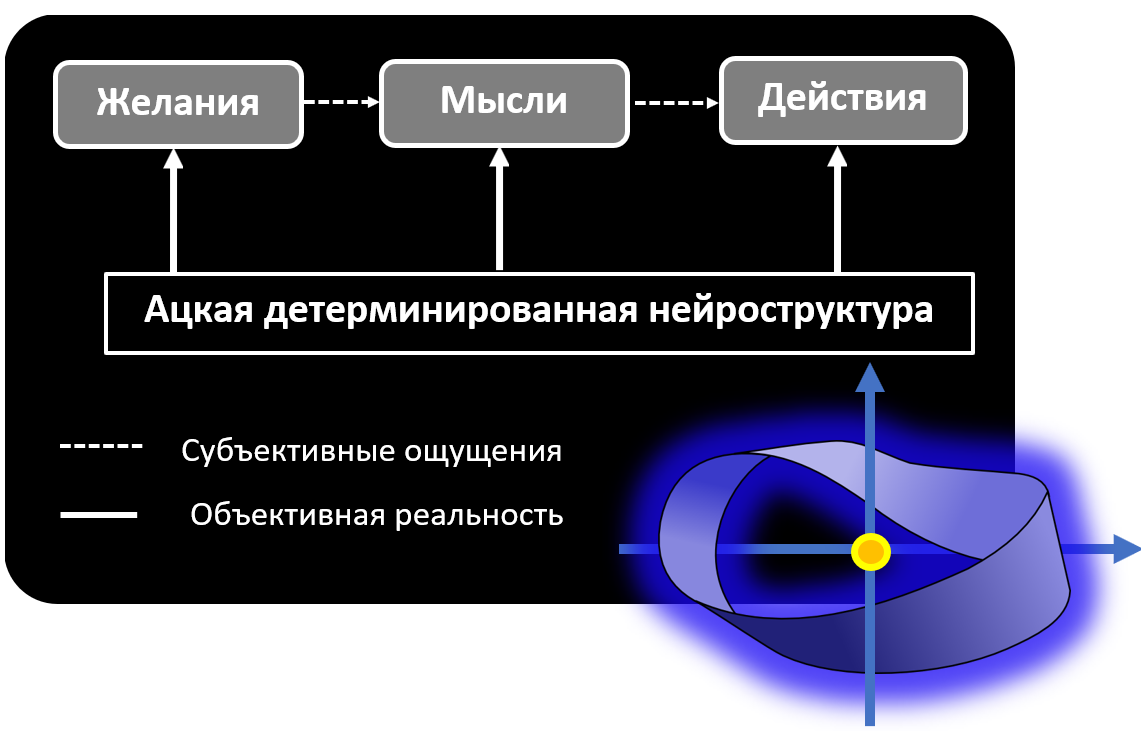

I noticed that more and more articles of a psychological and psychopharmacological orientation began to appear, from which there was a scientifically proven hopelessness. Either directly, or between the lines, it is implied that there is no free will, and we are slaves of our instincts, the biochemistry of the brain and the body as a whole. Various pictures are drawn - similar to the KDPV.

I want to share my thoughts in defense of free will. Let me emphasize that we are not talking about criticizing the scientific paradigm. Quite the opposite - it is an attempt to look at freedom from a scientific point of view. I understand that I am starting from an unfavorable, and maybe even knowingly losing position, but I will try to make a couple of castling and somehow build a defense line. If you like to discuss the unjustified and prove the unprovable with your friends over a mug of a pleasant drink, then please, under cat.

The most important question

The issue of free will is a cornerstone issue of philosophy and worldview, on which the lives and destinies of people ultimately depend.

When you start talking about free will, they often look at you like an idiot. Half of people do this because they do not quite understand what is at stake. The other half is because they understand too well. In order to be understandable to the first half and to lull the vigilance of the second, we will formulate this question in the most innocuous form, which nevertheless retains the entire urgency of the problem. So:

Can we influence our future?

There is nothing seditious about this issue. Any sane person, before doing something in his life, should try to answer it. At least for myself. Even if for this you have to make a shaman tambourine from the upholstery of your office chair. And go to the tundra to dance around the fire and drink a tincture of fly agarics.

Why prove the obvious

If you take me, for example, then I do not need proof of the existence of free will. I can feel it, like the five fingers of your hand. Sometimes I look at my hand, move each finger separately, and then clench it into a fist. When the hand obediently obeys my orders, I understand that I still have the power to change something in this world. And let me be told that this is a phantom feeling, like from an amputated limb. I know that I have freedom, as I know that I have thoughts and emotions.

Remember the story of how the wise men gathered and began to prove to each other that movement does not exist (the famous Zeno's paradox). One sage, indignant at these conclusions, got up and demonstratively walked back and forth, and then left the hall altogether.

I think that this sage, if they began to convince him that he has no freedom, would simply shatter someone's nose. I am reminded of an anecdote.

At the trial, the woman is asked:

- Why did you hit your husband with a frying pan?

- Why does he tell everyone that I am so predictable?

But what is obvious to some may not be obvious to others. Moreover, for others, something quite different may be obvious. And even if the same thing is obvious to everyone, it never hurts to talk about it, using various arguments of varying degrees of scientificism and emotionality.

I'm not guilty, it came by itself ...

First, I will try to understand a little with the humanitarian side of the issue. I understand that the following reflections will not add or subtract anything in terms of a pseudo-scientific approach to free will, but I still speculate about it.

If the importance of free will for the exact sciences can still be somehow disputed, then for the humanitarian branches of knowledge, free will in general constitutes their entire content. This is especially true for the theory of society and law.

Suppose that scientists would reveal all the true physiological reasons for human behavior. How the trial might look like in this case.

, – ?

— , , . , – – .

— ?

— , . . , .

— , ?

— , , . . . .

— ?

— . . . .

- Why did you stab him again (nine times in total)?

- Well, this is quite simply Your Honor. It is just a motor reflex, with a positive feedback loop. Pavlov wrote about this. It is a shame not to know about your position.

If you think this is absurd, you are wrong. There are already known cases of acquittals for diabetics who committed illegal actions with low sugar levels. It is with these facts that the famous researcher of the biochemistry of monkeys and humans, Robert Sapolsky, often begins his lectures.

Why free will is denied

In my opinion, the main reason for denying free will is in a person's desire to build a predictable world around him. And science is the main tool. Science studies causal relationships and helps to design safe and understandable environments.

But what is important here is that a correctly constructed predictable reality should give a person the right to choose, the right to exercise his freedom. Science must come up with a switch that turns lights on and off predictably. But the decision itself - to turn the light on or off - must remain with the person.

More specifically, I believe that the reason for the denial of free will is the desire of science to build a comprehensive, predictable picture of the world. This desire is due to the main task of science. But how far can the deterministic methodology be applied in the study of the world, and especially man?

If you have a hammer in your hands, then nails are everywhere. But maybe you shouldn't drive a nail into a human head?

A small step towards freedom

Removing the curse of determinism and fatalism requires just one small assumption:

Not everything in this world is determined by cause and effect relationships.

How this can be is a separate question and in the future I will touch on it. Science has already gotten a little flick on its nose when faced with quantum reality. At first she was taken aback by such strange things, but then regrouped, blew off the dust from the theory of probability that was not in demand until that time (it was then used mainly by gamblers), and instead of facts began to operate on the probabilities of these facts. Most of the patients calmed down. The most violent were tied to the beds. And the average temperature in the hospital has leveled off again.

I will express my idea of the universe. I see it as a certain scale. At one end, there is complete conditioning and clear work of cause and effect. At the other end is complete freedom, including from space and from time.

The question is in which direction on this scale should we move? Our ancestors have solved this issue for themselves long ago. The description of samsara as a complete triumph of cause and effect (karma) is the darkest description in Buddhism. And the main task was to free the causal wheel from the tenacious paws. In other religions, approximately the same conclusions were made.

God forbid anyone's consciousness to completely fall under the power of the causal mechanism.

Free will is at the core of science

I will try to show that the concept of free will is fundamentally present in science. As an example, I will take mathematics, which is known to be the queen of sciences.

One of the basic concepts of mathematics is function. As you know, the function has independent or free variables. The name itself suggests the right thoughts. This means that some free will can arbitrarily assign values to these variables, and mathematics must obediently indicate the value of the function.

It is also interesting to define the limit - the basis of mathematical analysis. Even a few creatures with free will is assumed here. One creature chooses the "predetermined value", and the other creature "the value of the argument at which."

The principle of my reasoning, I think, is clear. We choose terms that have in their definitions the words independent, free, and try to understand what this term means in the light of the presence of free will. For example - “degree of freedom” in mathematics and mechanics. You can find tons of other examples.

As you know, in order to have correct judgments, you need to call a spade a spade. Mathematics and physics are just those sciences where everything is called by its proper name. And if there are concepts of independent variables and degrees of freedom, it means that they are.

The old postulate trick has never failed

Of course, the most basic question is where freedom can come from and what physical laws determine its existence.

When science cannot explain some facts, it takes them for axioms. If you think that this is some kind of cheating trick, then you are wrong. This is a common scientific practice. For example, Einstein succeeded in doing this trick even twice: in the special theory of relativity, he took for a postulate the completely inexplicable constancy of the speed of light. In the general theory of relativity - the equality of gravitational and inertial masses, which was also an inexplicable, but precisely established scientific fact.

Likewise, we must postulate that mass and energy in our universe can manifest freedom. And her behavior in some part cannot be explained by cause-and-effect relationships. Science should not ignore free will. She must include it in her conceptual and methodological apparatus.

In the light of this idea, the correct question (I already mentioned this in another article) is not how freedom arises as a result of physical laws, but how physical laws restrict our inherent absolute freedom.

The second dialectical barrier

When they talk about dialectics, such related concepts are usually cited - hot-cold, heavy-light, good-evil. But in my opinion, these are weak dialectical pairs. There are stronger dialectical concepts. They cannot be mixed as easily as water in a can. And the transition between them is not that easy. And I would call them dialectical barriers.

As examples: form and content, strategy and tactics, matter and consciousness, information and energy, and, of course, predictability and freedom.

Let's take a closer look at the pair - information and energy. It is quite obvious that one cannot exist without the other. Any information has an energy carrier. Any energy carries some information. Despite the complexity and elusiveness of this relationship, humanity has overcome this barrier. And now we can design devices that combine energy and information in any proportions we need.

The concepts of determinism and freedom belong to the same dialectical barrier. Someday we will overcome this too. And we will design devices that combine predictability and freedom in the form and in those proportions that will be useful to us. And then artificial intelligence will become really strong.

Light of freedom

There is one story about the inventor of a perpetual motion machine. When he was told that perpetual motion is impossible, he replied: "My eyes tell me the opposite - everything in the universe is involved in eternal, causeless motion."

I have the same feeling when I try to think about free will. Everything in the universe is saturated with the spirit of freedom. This feeling arises, for example, when I try to comprehend the strange world of quantum physics and elementary particles.

For example, a particle of light - a photon. In his behavior, he shows incredible ingenuity and freedom. He moves to the target simultaneously along all possible trajectories. He interacts with whoever he wants and when he wants. He strongly opposes any attempts to observe. He is constantly in superposition with respect to any characteristics. He postpones all his quantum solutions for as long as possible.

We act in much the same way as a photon. When solving a problem, we consider all options. We postpone all our decisions until the very late moment. We do not like it when someone pokes their nose and measuring instruments into our affairs. We do not want and cannot decide, and we are in a superposition on almost all important issues.

We are made of light. And just as free. We just have a little more restrictions.