Jones Live Map - turn-by-turn navigation of the early 20th century

Modern GPS navigation is easily taken for granted, this technology is not new for a long time. In addition to the fact that navigators are installed in the dashboards of modern cars, any modern smartphone can suggest the route. But if you think that the history of in-car navigation systems began with the founding of Garmin in 1991, then you are wrong.

Smarter automotive history buffs might assume that car navigation started with Etak's navigator. The brainchild of engineer Stan Honey and financier Nolan Bushnell (co-founder of Atari), Etak's navigator was released in 1985 and did not use the military's global positioning system - the introduction of GPS will not happen in a few decades.

However, Etak's navigator paved the way for subsequent systems - it used digitized maps stored on cassette tapes so that they could withstand bumps or heating on hot days. The information was displayed on a vector CRT screen. Each tape contained 3.5 MB of map data. An electronic compass mounted on the windshield was connected to speed and direction sensors mounted on the wheels. There were two models on the market: the Etak 700 with a 7-inch screen for $ 1595 and the Etak 450 with a 4.5-inch screen for $ 1395. The card cassettes cost $ 35 each. At first, only San Francisco maps were on sale, after a while Etak released maps for other regions, and local stores of stereo systems and mobile phones installed the maps.

Despite a good start, sales soon inevitably dropped. In 1989, Etak was bought by News Corporation for $ 25 million, then bought by Sony, and after a series of resale Etak became part of Tom Tom.

However, it is much easier to navigate American roads now than it used to be. For most of the country's history, travel has taken time, patience, and luck, and devices like Etak's navigator have made a difference. However, like modern GPS systems, Etak's navigator was not the first portable car navigation system.

Early roadmaps

Maps of the largest cities in America first appeared in the 18th century - around the same time the first road atlas appeared. In 1789, New York-born Christopher Colls' "Survey of the Roads of the United States of America" presented road maps from Williamsburg, Virginia, to Albany, New York. This review was not a single publication - it was distributed in parts by subscription. It was expected that subscribers would collect map fragments into a single atlas. For three years Kolss managed to publish 83 fragments, each of which contained two or three cards. Christopher was unable to complete his work for one simple reason: in the late 1700s, road maps were practically not used in the United States.

At the end of the 19th century, most American roads looked much the same as a century ago - they were just paths trod through the countryside by Native Americans and the wild animals they hunted. Later, there were roads for carts, stumps were uprooted from them, and the surface of the dirt road was leveled. There was no federal road construction system yet, so federal roads did not exist. The trips were mostly short and were made by residents familiar with local roads and routes, so there was no need for road signs. Unsurprisingly, until the early twentieth century, most cross-country travel involved traveling by rail rather than a van. This is why Rand McNally's first map, printed in 1872, was a railroad guide.

But the advent of the automobile in 1895 changed everything.

Cars were not limited by the timetable of railways and stagecoaches, they gave freedom of movement. It soon became apparent that finding a way from city to city was extremely difficult, leading to the creation of the Official Automobile Blue Book.

Unrelated to the current Blue Book, this driver encyclopedia guided motorists from one place to another based on the distance between cities and road objects. The book also listed local attractions, state automobile laws, hotels, repair shops, service stations, and ferry and steamboat timetables and fares. The guide's popularity skyrocketed when AAA sponsored it in 1906.

However, the "Blue Book" had competitors.

In 1907, cartographer Rand McNally published a series of Photo Guides, which combined maps and photographs with arrows to indicate turns. In 1915, Thomas Bros. was founded in Oakland, California. Maps, which developed a unique page-by-page mapping system that eliminated the need for folding maps. Obviously Rand McNally liked her. By 1924 Rand McNally's "Motorist Assistant" appears.

Today this edition is known as Rand McNally's Atlas of Roads. There were other guides: The Automotive Green Book from the Massachusetts Automobile Law Association, The Official King's Guide by Sydney J. King from Chicago, The Interstate Travel Guide from F. S. Blanchard and the Worcester, Massachusetts company, and many others.

While these guidebooks were very useful and important, they had their limitations. Many used local attractions in their instructions, adding descriptions like “turn left at the pharmacy”. If such landmarks disappeared, then problems arose with the construction of the route. This may be why folding paper roadmaps have become so popular. Gulf Oil, a Texas oil company founded in 1901 by the Pittsburgh Mellon family, is believed to have created these cards to advertise their gas stations, the first of which opened in 1913. (Most of the major oil companies also issued such maps until the OPEC oil embargo in the 1970s. Today, state governments print roadmaps.)

Cars on duty in front of the Grand Palais at the 1906 Paris Motor Show.

Given the Americans' longstanding fascination with mechanizing every aspect of their lives, it should come as no surprise that experimental navigation instruments soon emerged. They are a kind of prehistoric ancestor of modern navigation systems. One of the earliest and most successful first appeared in 1909: the Jones Live Map.

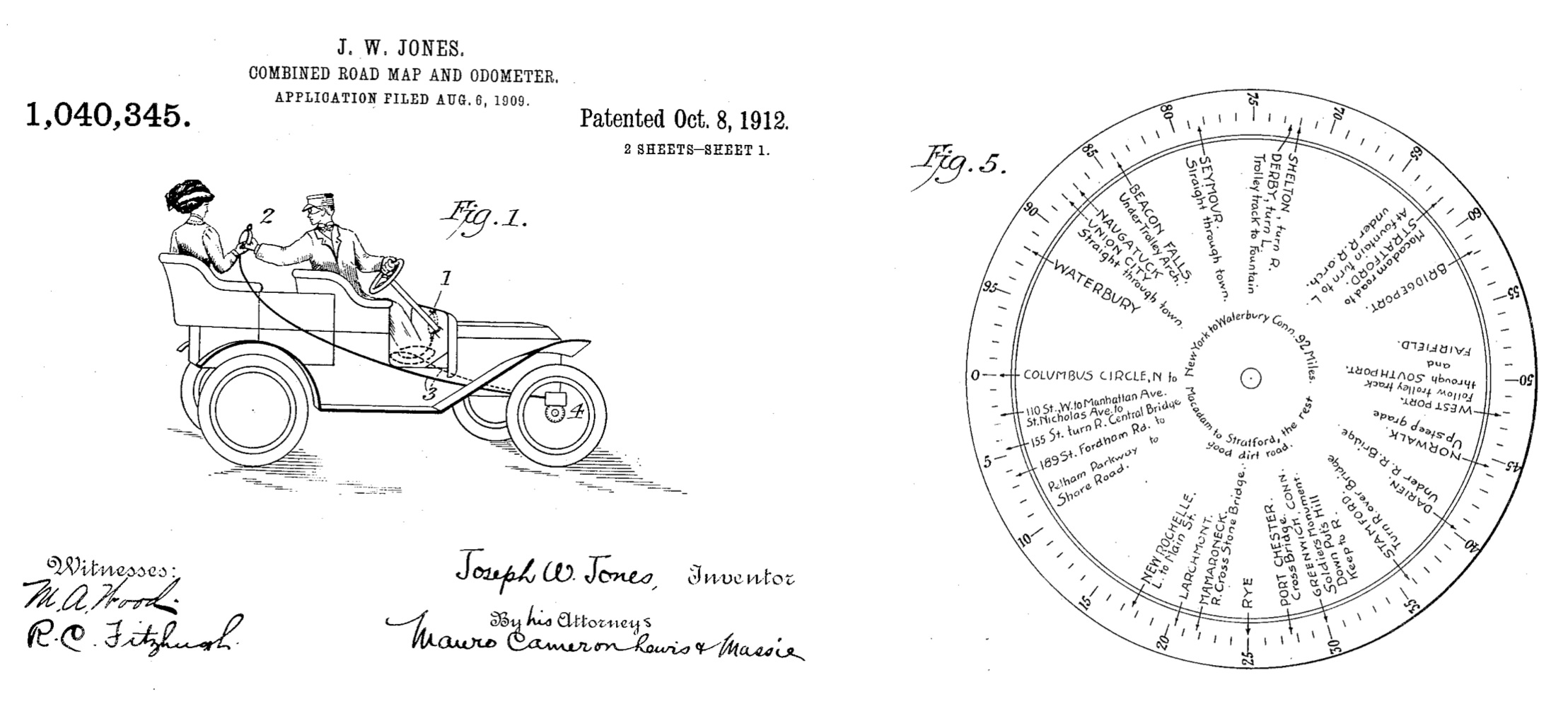

This illustration from Jones' patent shows a flex cable that connects the system to the front wheels.

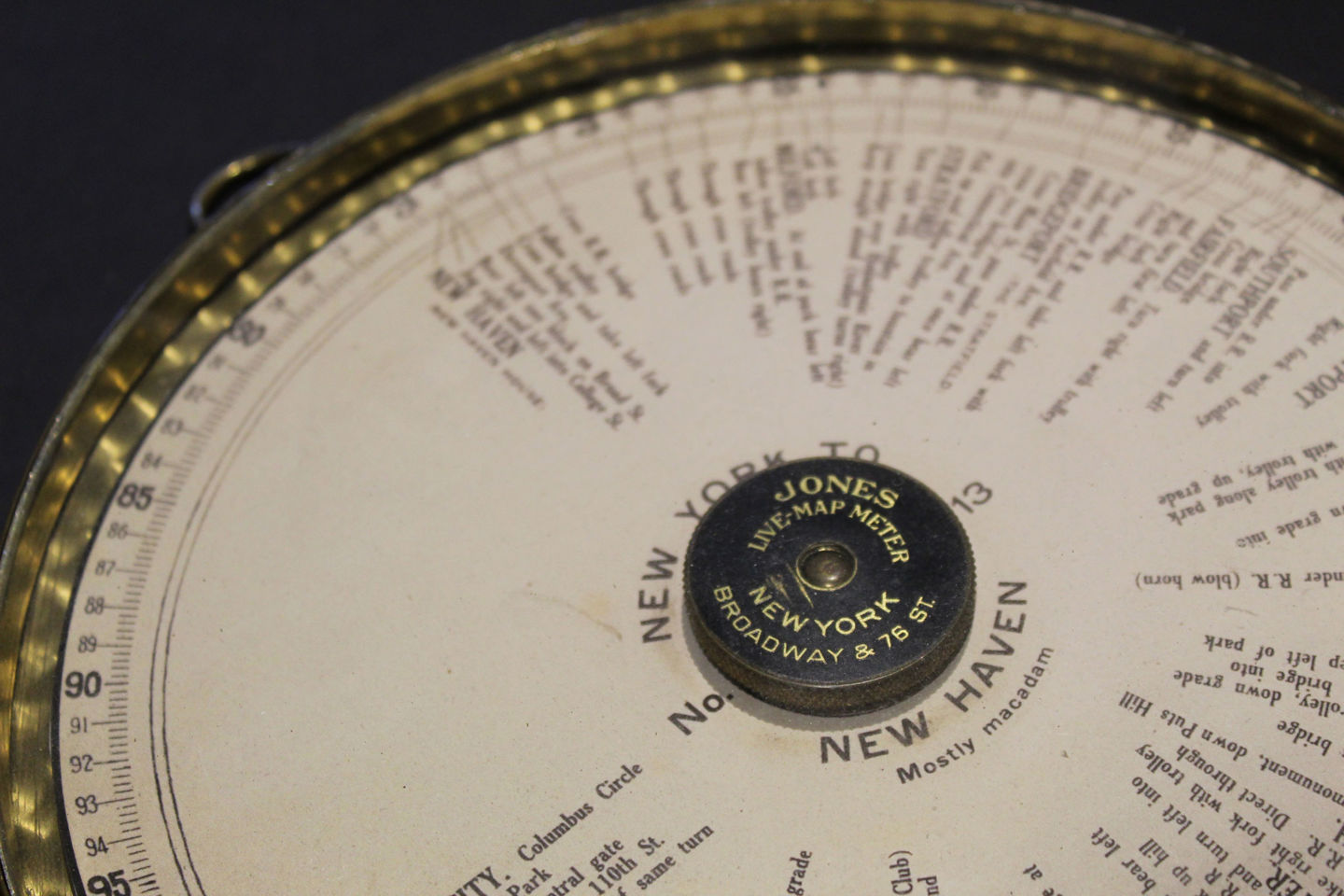

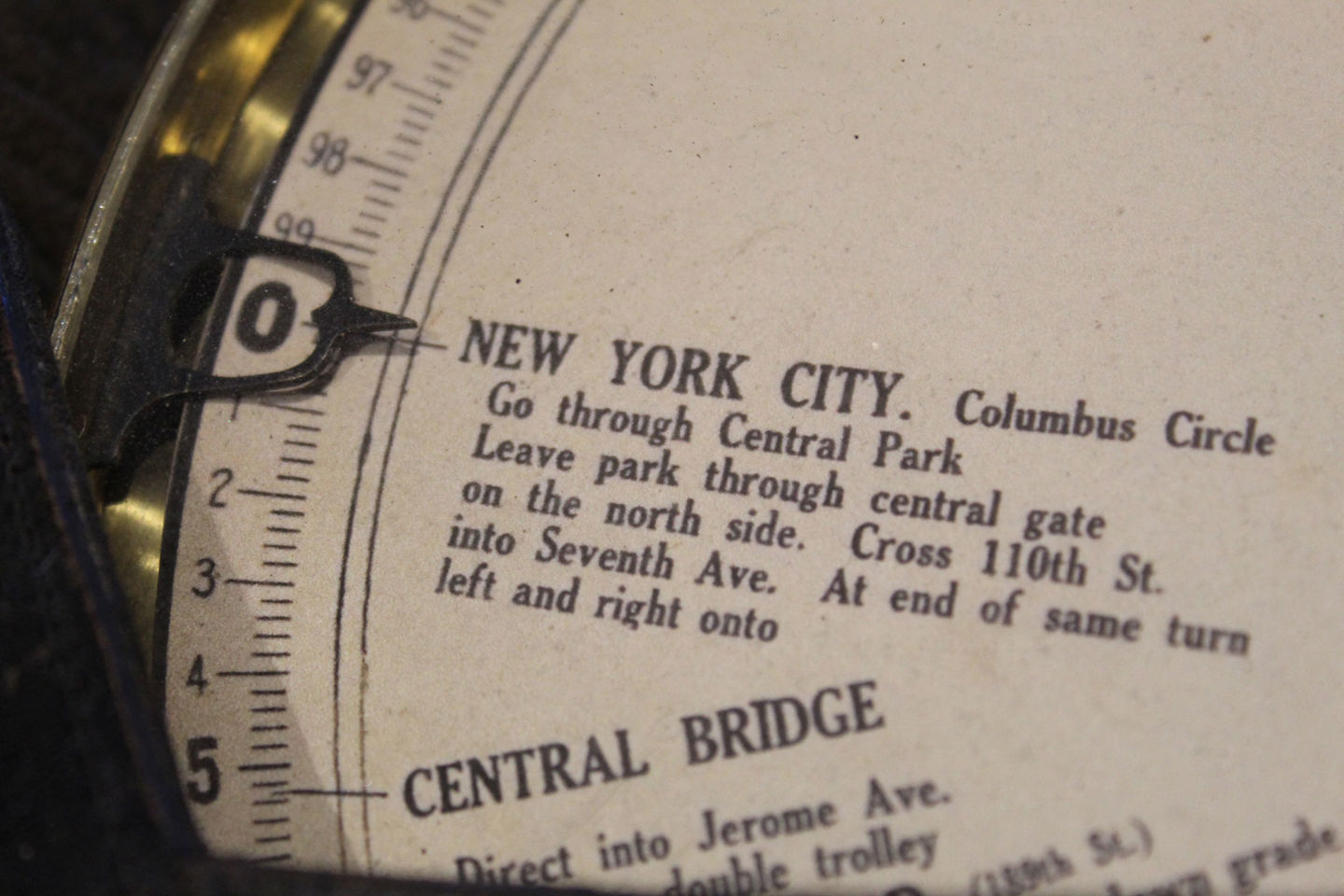

The original Jones Live Map system in a leather case.

Jones Live Map is one of the first attempts to create a navigation system in the early 20th century.

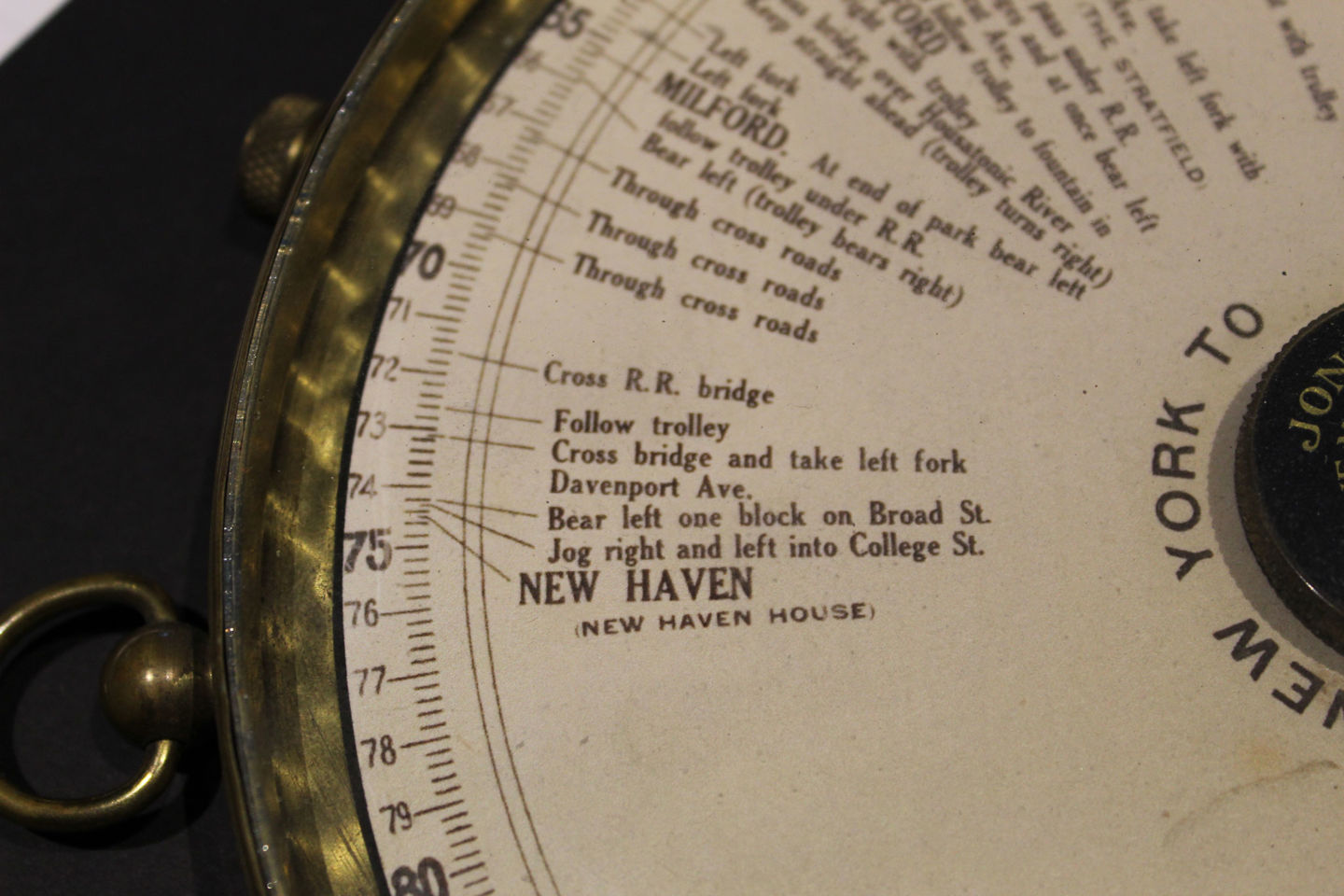

The fastest route from New York to New Haven, Connecticut.

To navigate the live map, you need to leave a certain point.

After a while you will find yourself at your home in New Haven.

Joseph W. Jones was born in Saratoga, New York in 1876. He was an engineer trained by audio pioneer Emil Berliner, whose invention of flat-disc recording overshadowed Thomas Edison's cylindrical discs in the market. Jones perfected the method of engraving on a wax master disc and received a patent for this technology in 1901. After selling a patent to the Columbia Graphophone Company for $ 25,000, Jones used the money to create his Jones Instrument Company, which included a factory in Rochester, New York, and a four-story showroom in New York. This showroom opened in 1907 on the northeast corner of Broadway and 76th Street, in the heart of Manhattan.

It was Jones who created his speedometer, which was installed on a Winton car for an endurance run from New York to Buffalo in 1901. He applied for a patent in 1903 and received it in 1904. Jones' speedometer used a flex shaft cable and a gear-driven attachment to the front wheel. Jones used a similar design in his other invention, which was a "combination of a roadmap and an odometer."

The live map was a glass brass dial attached to the edge of the driver's side of the car and linked to the car's odometer. Before setting off, you were required to purchase one of the 8-inch paper discs of driving directions collected by the American Tourist Club. The length of the route was indicated at the edge of each disc, with each mark representing one mile and a small mark representing a fifth of a mile. The directions were printed along key points of the run (like spokes on a wheel) and described the road surface (asphalt or dirt), intersections and level crossings.

The disc was installed on a rotating turntable platform. The disc was installed at the starting point of the route. In the direction of travel, the disc rotated in proportion to the speed of the car, indicating what to do, which way to look and where to turn. Each disc covered about 100 miles, having traveled that distance you had to stop and replace the disc with the next one. Of course, if the driver did not move in the same lane, then the accuracy of the device decreased. To solve this problem, Joseph's brother Ernest improved the system in 1913 by reducing the number of rotations transmitted to the device if the driver was chaotic.

The counter cost $ 75 and came with 12 discs. Additional discs cost 25 cents each. You could also buy a set of discs, then each of them cost 15 cents. An advertisement Saturday night said, "Having it [a live map] with you is like driving with someone who knows every road, every turn, every intersection, every landmark, every tricky route and every fork in the world."

By 1919, Jones was offering drives with over 500 routes from New York to California, but his company was not the only player in the market. In fact, Jones' system has been rejected five times by the US Patent Office for being similar to other devices.

, Google Patents, , « , , , , , ».

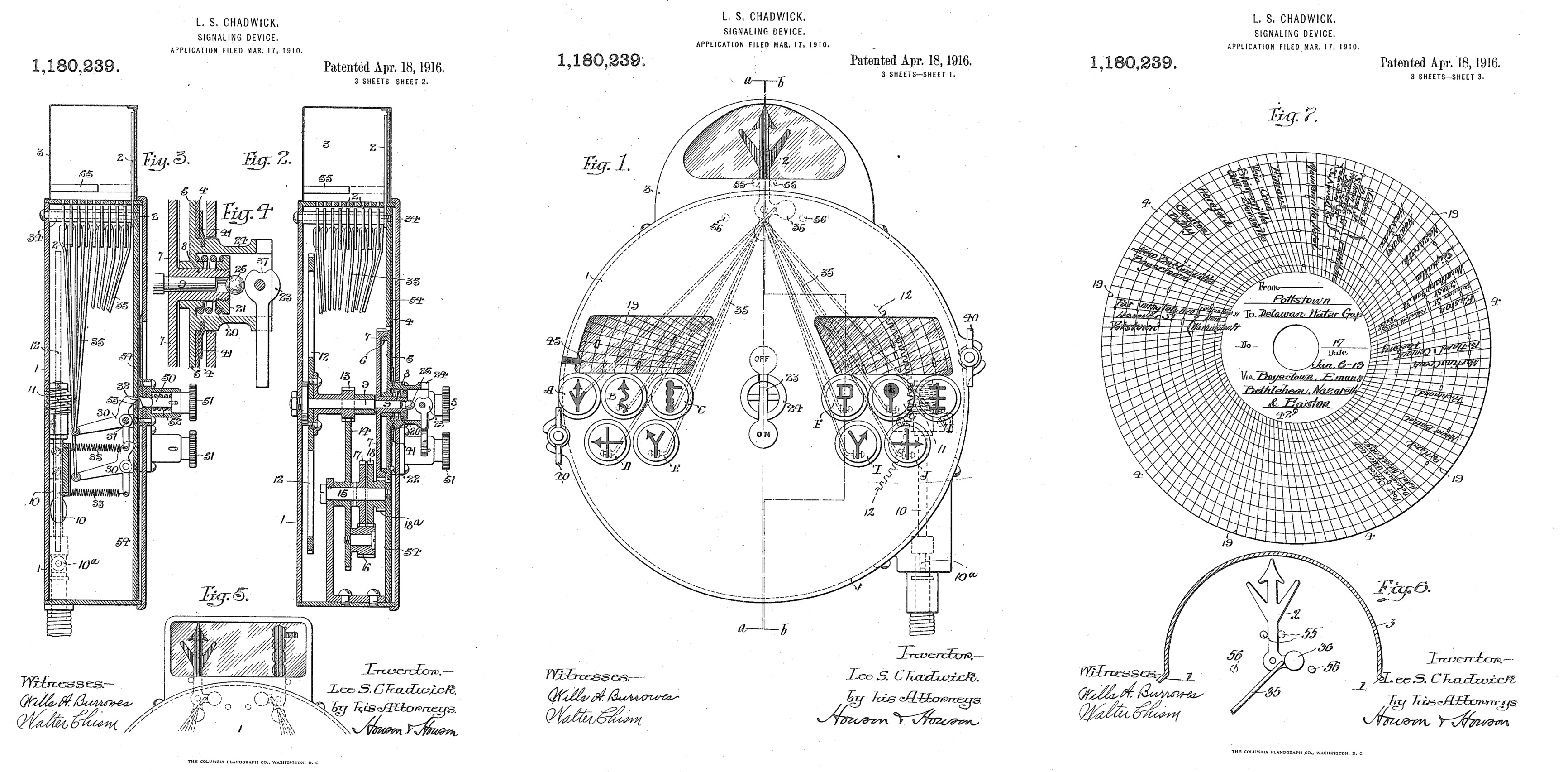

One such device was the Chadwick automatic road guide, invented by Lee Chadwick of Bantam, Connecticut. Born in 1875 on a Vermont farm, Chadwick earned a BS in mechanical engineering from Purdue University in 1899, a fact that sets him apart from the many self-taught competitors like Jones. In 1903, Chadwick founded his own automobile company, producing four- and six-cylinder cars. He sold it in 1911, focusing on creating and selling Road Guides, produced in Cleveland, Ohio.

As with Jones' live karts, Chadwick's road guide used a disc connected to the front wheels with a speedometer cable. although the disk itself was different and had a different purpose. Chadwick's disc was perforated and had many holes, like a sheet in a mechanical piano. In March 1912, Motor Age magazine explained that the instrument used “a set of signals controlled by compressed air. These signals are given when the holes in the paper disc line up with the air tubes ... The signals are in 10 different colors, and the device is visible enough to be seen from anywhere in the vehicle and at any speed. The device is equipped with a small electric light inside the case, making it easy to monitor it both at night and during the day. The distance over which signals should be received can be set by the driver.… When a signal is given, a sound is emitted inside the housing, notifying the driver of the signal change and the corresponding instruction. ... Traffic records currently cover most of the eastern states, but records of the most important routes across the country are expected to be developed within a few months. "

The log also says drivers could even make their own route records using the record attachment that came with the device. “This device consists of a keyboard with ten signals, with which the discs can be marked during the trip. To make such a recording, you need to install a blank disc on the device and drive along the road you want to record. Two models of the "Road Guide" were presented on the market - for $ 55 and $ 75.

Motor Age also noted that the decision was not perfect. Drivers had to slow down to 20 mph each time the perforations were made, and even so, the system was not foolproof. “If you want to make a full description of the route, then you need to record the entire trip in great detail,” the magazine advised.

Another popular manufacturer of roadside assistants at the time was The Baldwin Manufacturing Co. from Boston, Massachusetts. This company began selling the Baldwin Auto Guide device in 1910. Much less cumbersome than live maps, the Auto Guide was a small metal cylinder with a window attached to the steering column of a car. Built into the cylinder was a strip with a card wound on spindles (like a film inside a camera). The map contained directions for changing directions, and for the next instruction, the driver had to scroll the map by hand using a small wheel on the side of the cylinder. The uniqueness of this device lies in the fact that it was supplied with lighting for night driving, powered by a battery.Auto Guide took inspiration from one of the oldest forms of the map, the striped map. Examples of such maps date back to the fourth century; Roman maps from that era described the route from Great Britain to India.

Other devices have been patented, but no one remembers them.

Device in your car

Perhaps the most amazing early car navigator was patented in 1916 by Manhattan resident George Boyden. Boyden never owned a car, he was a chauffeur, which may explain his invention - the alarm system for vehicles. He used a phonograph to play directions with a megaphone. The player was installed in front of the driver on the steering column. The phonograph was attached to the front wheels of the car and announced the change of direction with commands recorded on the plate of certain points of the run, so this is kind of a harbinger of Siri or Google warning you about turns now in 2020.

Time passed, new mapping devices appeared, not all of them were as simple as a paper folding map. And then the Federal Highway Act of 1921 transformed motoring by mandating that single or two-digit numbers would be used on major highways, and three-digit numbers would be used on access roads connected to major highways. Important east-west routes sometimes ended in zeros, and major north-south highway numbers ended in ones. Rand McNally was one of the first mapmakers to switch to the new system.

Given the simplicity of paper maps and the fact that they could simply be replaced when roads changed, it's no surprise that bulky custom navigation systems have never been popular. It took decades for the navigator from Etak and Tom Tom to appear.

By the time paper maps took over, inventors like Joseph Jones had moved on. He sold the taximeter patent to the New York Taxi Company. The speedometer patent was sold to Stewart-Warner. He developed an aviation tachometer that was used until the early 1960s. A number of other inventions can also be noted - an electric car horn, a decorative tire tread, an electric massager and a shoe polishing system. He even made radios, although Jones Radio Manufacturing, founded in 1924, was not successful in the market. It lasted 6 years and closed, although its Manhattan showroom at the intersection of 76th and Broadway has survived, albeit in a modified form.

The next generation of car navigation systems did not appear until the 1980s, but this is alreadyanother story .

- Long and winding road to GPS adoption in all vehicles

- 1971 Cassette Navigation System

Subscribe to the channels:

@TeslaHackers - a community of Russian Tesla hackers, rental and drift training on Tesla

@AutomotiveRu - auto industry news, hardware and driving psychology

About ITELMA

- automotive . 2500 , 650 .

, , . ( 30, ), -, -, - (DSP-) .

, . , , , . , automotive. , , .

, , . ( 30, ), -, -, - (DSP-) .

, . , , , . , automotive. , , .

Read more helpful articles:

- Free Online Courses in Automotive, Aerospace, Robotics and Engineering (50+)

- [Forecast] Transport of the future ( short-term , medium-term , long-term horizons)

- The best materials on hacking cars from DEF CON 2018-2019

- [Forecast] Motornet - data exchange network for robotic transport

- 16 , 8

- open source

- McKinsey: automotive

- …