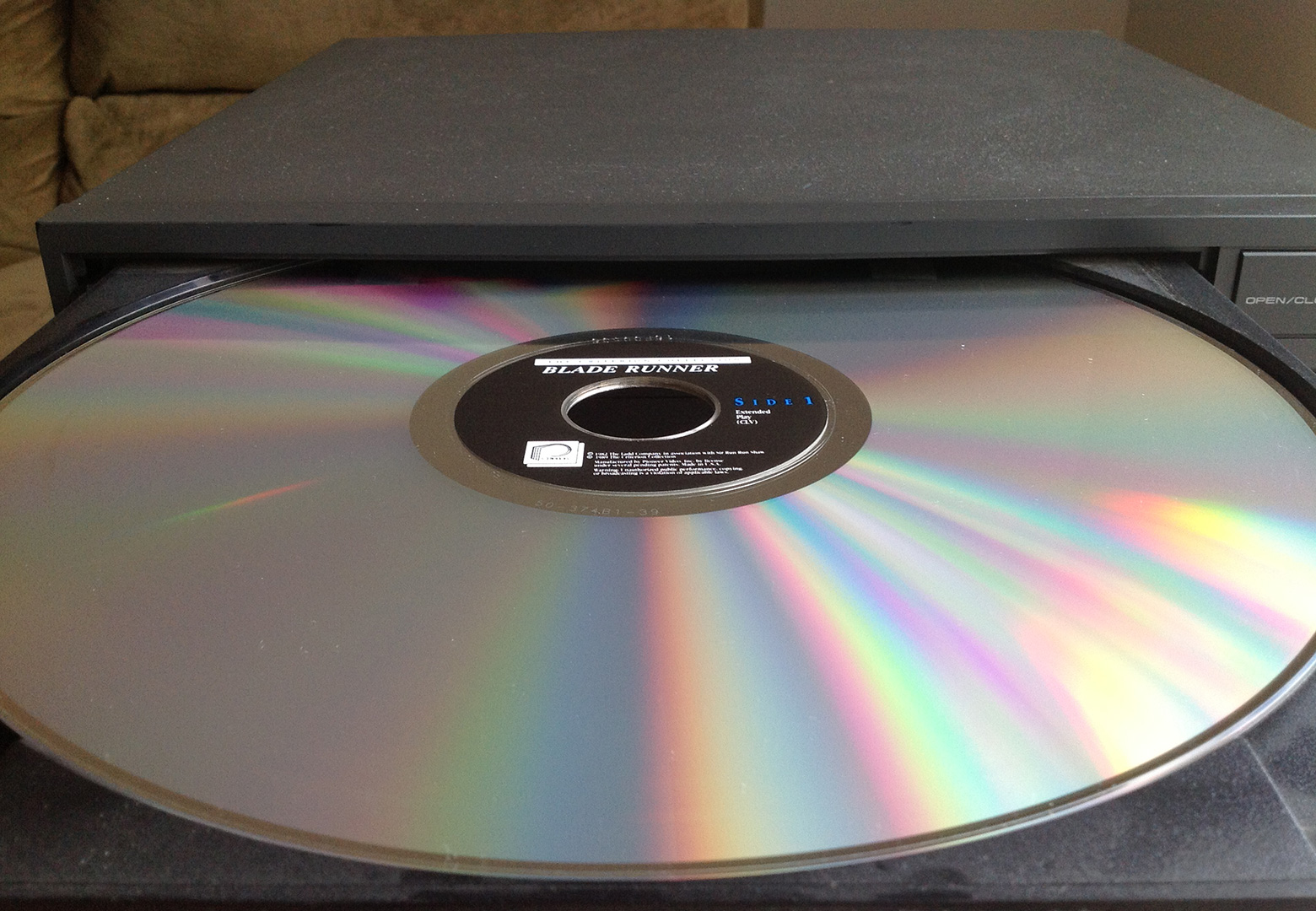

The reality is more varied: every successful storage format is a few dead competitors that the market has rejected because of the high price or low quality. Not all of the losers went into oblivion right away. Some of them existed in parallel, keeping a tiny market share in the shadow of the winning format. Blade Runner movie disc in Pioneer LaserVision LD-V2000. Photo by Electric Thrift .

Such a fate was prepared for LaserDisc. In the late seventies, films for home viewing began to appear for the first time on optical drives. On each side of the 30-centimeter overgrown CD, an hour of excellent quality video of 425 horizontal television lines fit. This is much nicer than a VHS picture (240 lines). Support for digital encoding and 5.1 surround sound came a little later. Releases were often accompanied by alternative audio tracks with commentary and visual bonus material. There was no need to rewind anything, chapter navigation worked like in DVD.

Typically, a story about a less popular, technically more advanced format ends with regret about its prohibitively high cost. But in the early days of LaserDisc, both laser players and discs were cheaper than VCRs and cassettes. Then why hasn't the laser disc supplanted VHS?

Table of contents

- The path to DiscoVision

- Joining forces with Philips

- Later than the rest

- Ahead of its time

in the second part of the post:

- Not a competitor to magnetic tape

- Life after DiscoVision

- Conclusion

The path to DiscoVision

The history of any modern technology is thousands of organizations, hundreds of geniuses, and decades of tangled development that date back to the post-World War II tech boom. LaserDisc, which would later spawn the CDs we already know, is no exception.

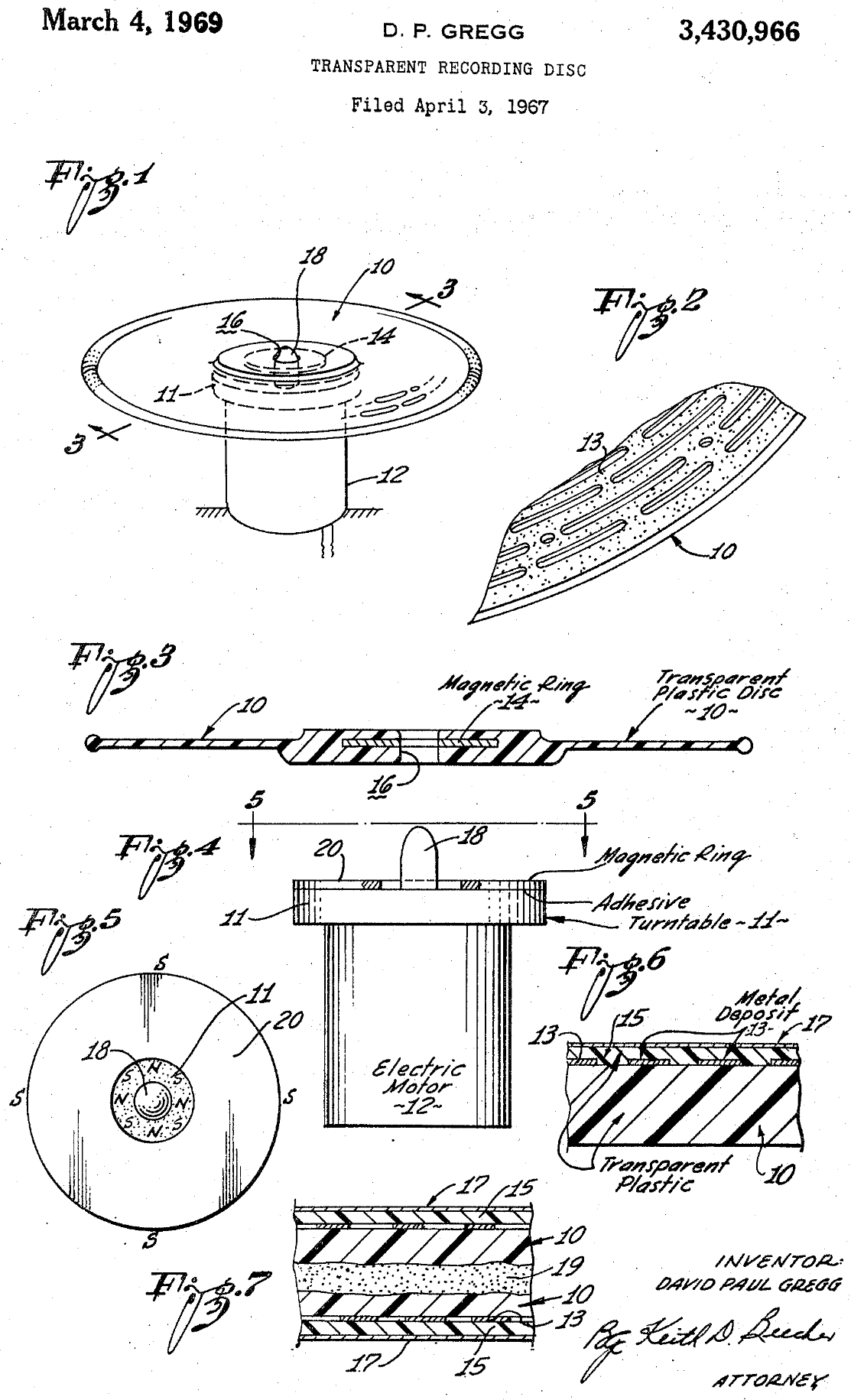

For some reason, it is customary to appoint David Paul Gregg as the first inventor (or even the "father") of laser video discs . As the "eclectic engineer" - as he called himself - claimed, the idea of recording video onto an optical disc in a set of tracks came to him in the late fifties when he was working for Westrex Corporation. In fact, Gregg pushed the development of technology, but he is quickly lost behind the figures of other engineers and managers, and his patents are only slightly similar to the familiar laser discs.

By the early sixties, it was becoming apparent that Bing Crosby Enterprises was losing the audio format war. Its founder, American singer Bing Crosby, did not like to perform his programs for radio a second time for the West Coast of the United States. They got out of the situation by writing to disk. But the sound quality of the shellac record left much to be desired. Crosby saw the obvious advantages of tape and showed a business streak, but lost out to North California's Ampex. To cut losses, he sold his company.

3M (Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company), which previously produced magnetic tape for Crosby, took over Bing Crosby Enterprises and renamed it Mincom. Mincom's core business will be codenamed A, B, C, and D. We are interested in the fourth, Project D is an assessment of the technological feasibility of a low-cost video recording system for the consumer market. Gregg took over the project and joined Mincom after being fired from Westrex in 1960.

The events that followed showed how much Gregg's personality was incompatible with the corporate culture of a large company. At Mincom, Gregg will only last three months. The paranoid and unsociable inventor constantly thought that they wanted to steal the idea of a video disc from him. It didn’t add to the peace of mind when one of his colleagues secretly from Gregg consulted the Stanford Research Institute about the project.

This was the last straw. One fine Sunday, the engineer arrived at work, put his things in his truck and drove off. Gregg's fears were in vain: on 3 out of 19 Mincom video patents, his name is either as the author or co-author.

Back to the Future 2 correctly predicted that LaserDisc would be phased out in 2015. Trash can be seen behind the characters: pressed stacks of double-sided 30-cm optical discs.

In 1965, a massive exodus of engineers from Mincom fuels the staff of Winston Research. Gregg saw the desire to create a videodisc behind this and joined the company to finally make his venture a reality. Others recall that the company wanted to do magnetic tape. Be that as it may, but almost immediately after the founding Winston was charged with theft of audio patents from 3M.

Subsequent legal proceedingslasted several years and laid the foundation in the United States for future ships in the field of electronics. Even before his graduation, Gregg decided to leave the company, since there was no real work on his videodisc. With him from Winston, the inventor took the talented engineer Keith Johnson, with whom he founded the Gauss Electrophysics company.

The new company took up tape copying techniques. To create commercial audio releases, each tape must be copied from the master - it cannot be simply printed as a gramophone record. This process is slow. If we are talking about large commercial volumes of production, it is highly desirable to copy faster than real time, and the faster the better. Media companies were happy to buy equipment from Gauss Electrophysics, because at that time the company's copiers were faster than others - up to 32 times faster than playback speed .

This is how Gauss made a name for herself in the music industry. The company had a trump card in its hands - a technology blueprint for the imminent home video revolution. It remains only to find among their buyers willing to invest in development.

In 1967, Gregg and Johnson presented the video disc design to Philips NV, hoping to secure development funding. The Dutch electronics firm took the idea coldly. Capitol Records, another Gauss client, also dropped the partnership. A large media conglomerate MCA became interested in the idea of recording films on disc .

The organization, whose name stands for Music Corporation of America, did not develop electronics. But the motivation is clear: there were 11,000 films lying dead in MCA warehouses, and creating a new method of marketing this content promised wealth. In February 1968, MCA acquired a 60% stake in Gauss Electrophysics for $ 300,000. It only remained to develop the format itself, and the trick was in the bag.

It is worth noting that MCA did not know about those 19 3M patents, and did not think about demonstrating for Philips at all. All this will come back to haunt the MCA later. And if 3M has to pay off with money, then Philips will be a useful partner. Both Gregg and the MCA were completely unaware that around the same time, somewhere on the other side of the earth in Eindhoven, Netherlands, Philips began developing its optical video disc. History is silent about the role of Gregg's demonstration on the Philips internal solution.

However, the paths chosen were initially very different. By 1969, a reflective video disc will appear inside Philips. What Gregg asked for money was transparent.

To show that Gregg laid the foundation for LaserDisc, one of his patents from the second half of the sixties is usually cited, for example, 3,430,956filed in 1967. In fact, these patents are far from LaserDisc: they describe a transparent disc on which a pattern is applied. Tracks from this Gregg's disk would have to be read, illuminating from one side and receiving light of varying strength on the sensor from the opposite. Even the tracks do not go the same way as in LaserDisc or CD: in Gregg they go like in a gramophone record, from the edges to the center. Such a medium was proposed by Gregg and Johnson to the MCA for films. Illustration from patent 3,430,956 .

And again began what had already happened at Mincom - Gregg could not get along in the structure of a large corporation. When asked about the development of a video disc, the management was silent. Instead, Gregg was asked to focus on tape replication machines. To oversee Gregg's work, MCA hired optics specialist Kent Broadbent. Suddenly, Broadbent suggested developing a reflective disk instead of a transparent disk, but he wanted to work on it independently of Gregg.

Gregg did not last long under the leadership of MCA. Three months after the takeover, he stepped down as president of Gauss Electrophysics on the condition that he would no longer be involved in the videodisc project. The later formed LaserDisc development team hardly mentions his patents in interviews.

Joining forces with Philips

MCA made films and television programs, and video development was far from the company's core business. But Broadbent managed to collect engineers and "knocked out" the money. You need to speak the same language with your bosses: he compared the amount of several million dollars for a project with the budget of one film.

Since 1969, the rapid development of a new format begins, the separation of the MCA Laboratories division from MCA and even the construction of a factory for the production of discs - again, Broadbent's efforts. By 1971, the MCA management was shown a prototype of a flexible video disc.

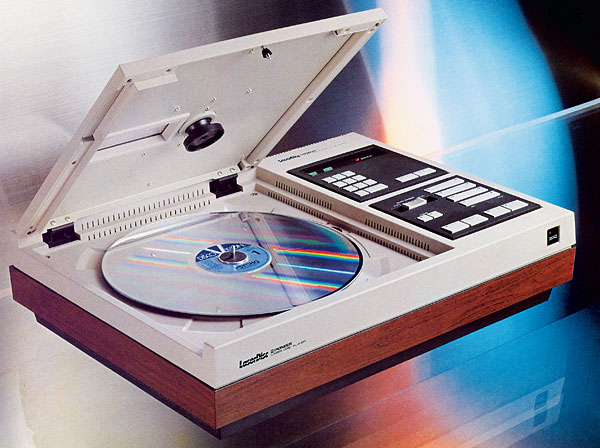

DiscoVision FSX-101. In the eighties, Pioneer would fix the name LaserDisc as the brand name and LaserVision as the format name, and in the early years, Disco-Vision was also hyphenated. The confusion in branding is even greater: the Magnavox players had the inscription MagnaVision, and some discs came out under the name Laser Videodisc. Source: AVS Forum .

The first demonstration of a working prototype outside of the company took place on December 12, 1972 at the Universal Studios booth. The DiscoVision FSX-101 device played 7 minutes of video, consisting of a cut of the MCA movie catalog. And it was far from the LaserDisc that would become available to consumers in 1978.

The technical specifications presented were different from the final product. On a flexible (not rigid) 12-inch disc made ofMylara will fit 20 to 40 minutes of video, MCA said. The disc is one-sided. Like the LaserDisc, the prototype spun up to 1800rpm when played back and read from center to edge. The MCA promised that DiscoVision is about as easy to print as a vinyl record, and it only costs 40 cents to produce a single disc.

Another machine was able to hold a stack of ten discs and load the next, which gave 3 to 6 hours of relatively continuous playback. Probably, the designers thereby wanted to compensate for the need to frequently change the disk. Source: AVS Forum .

Among the guests were representatives of major electronics manufacturers, including Dutch Philips. At that time, the Dutch already had a working prototype, although he only read the glass master, and not copies like MCA's. Philips immediately contacted the MCA, but there was no standards war.

Of course, two optical discs could compete. But it was not profitable for both companies. MCA struggled to find a partner to make DiscoVision turntables. Despite the spectacular demonstration of the prototype, electronics manufacturers were wary of the media company, and in Japan and Europe they simply did not know it. Philips, on the other hand, did not have a library of content as powerful as MCA could boast.

And optical disks also have a common enemy. At that time, RCA has promised is about to start selling SelectaVision systems and fill the market with cheap drives the CED . Such devices promised to cost less: CED videotapes were read with a needle, not an expensive laser. CED was due out in 1981 and would fail miserably, but at the time it was a real threat.

In September 1974, after lengthy negotiations and negotiation of terms, MCA and Philips began a period of cooperation and free technology transfer. The companies' laboratories exchanged information and standardized their designs. So the disc “hardened” and acquired its final characteristics. Philips took over the production of the turntables, and MCA prepared to replicate the discs.

At the same time, relations among the "top" were heating up. When the standard was finalized, Philips tried to obtain an international patent, which would give the Dutch total control over the technology. After bitter controversy and the threat of long and expensive litigation, future royalties from the disc's licensing were split equally between Philips and MCA. The markets were also divided: Philips departed Europe, and MCA took the United States.

Later than the rest

LaserDisc did not hit the market because it came too late. This is often called the reason for the low popularity of the format throughout its entire period of life.

This is partly true. On May 10, 1975 in Japan, Sony introduced Betamax videotapes and VCRs. On September 6, 1976, the Japanese Victor (JVC) began selling VHS systems. Even Philips itself released Video Casette Recordings in 1972, and switched to Video 2000 in 1979. These were the first relatively affordable consumer VCRs aimed at the average user.

Comparison of Star Wars in VHS and LaserDisc release. The optical media not only gives a better image, but also does not use pan-scanning , keeping the original aspect ratio.

Meanwhile, the development of the LaserDisc optical format stumbled upon new challenges. Now American anti-monopoly officials have intervened in it. In August 1975, the US Department of Justice accused the MCA and Philips of violating the Sherman Act . The two companies formed full control over the production of the video disc and the devices for playing it, as well as the content that was distributed on it. Such collusion could create a monopoly, which is dangerous for the market.

The MCA ignored much of the regulatory investigation, so Philips had to meet with the commission. The Dutch have rightly stated that if the DiscoVision project is pursued, then RCA will be in this advantageous monopoly position, which they want to avoid, with their CED videotapes, which were about to be released. Ultimately, any company’s films could be released on videodisc, as MCA was happy to license the content. The regulatory proceedings did not end with anything.

For all its difficulties, the Philips-MCA collaboration continued. MCA hastily printed discs. Philips even acquired the American company Magnavox to repair turntables in the United States. However, the assembly lines at the Knoxville plant in Tennessee were not yet ready, so the laser players were urgently assembled in Eindhoven in the Netherlands and shipped to the United States by air.

For additional safety net MCA also got itself another partner - "electronics". Since Philips ditched the industrial use of the DiscoVision format, MCA got a reason to license the technology to someone else. Pioneer's scale was not comparable to Japanese giants like Sony, Matsushita or JVC, but the company still wanted its own home video format. In October 1977, MCA and Pioneer form a joint company, Universal Pioneer Corporation, to manufacture turntables in Japan. The MCA didn't yet realize that Pioneer had stepped forward to take full control of the format.

Ahead of Christmas, on December 15, 1978, DiscoVision turntables bearing the Magnavox logo and the first optical discs hit the market in Atlanta, Georgia. The products are branded with the word "disco" in the name. It took 9 years from the beginning of development to the product on store shelves. The first batches are swept away in hours, only next year LaserDisc can be bought throughout the United States. At the time of DiscoVision's first sales in the United States, cassettes have long been on sale. VHS began to conquer the American market in June 1977 , Betamax in November 1975 .

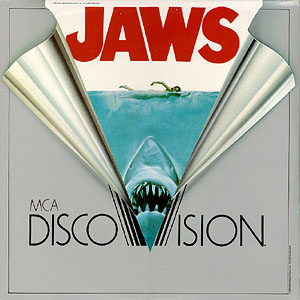

"Jaws", the firstfilm on LaserDisc, $ 16, December 1978. All DiscoVision releases have followed this visual style. The rapidly changing political climate is interesting: already in the reprint on LaserDisc in 1981, the bather's chest will be slightly covered with water bubbles.

On the other hand, the prevailing delay is not a sentence. The affordability of the first video recorders for the home was relative only when compared with the sky-high professional systems like U-matic . In fact, they cost the same as a used car. In the US, the first Betamax LV-1901 VCR was priced at $ 1,225, and the MSRP for the first Vidstar VHS deck was $ 1,280.

A laser player Magnavox 8000 with better picture quality and support for multiple audio tracks went on sale with a price tag of some $ 775. Even if he arrived a little later, it may seem that the lovers of chewing magnetic tape were in danger of defeat.

To release a film on cassette, you need to record a video, which is slower than replicating laser discs, which, as MCA so often repeated, will not be more difficult than printing vinyl records.

Cassettes were also expensive: $ 15–20 apiece for an empty one in retail. The studio's royalties are also added to the price of the cassette. The final price of a film on cassettes ranged up to $ 40-70 per film.

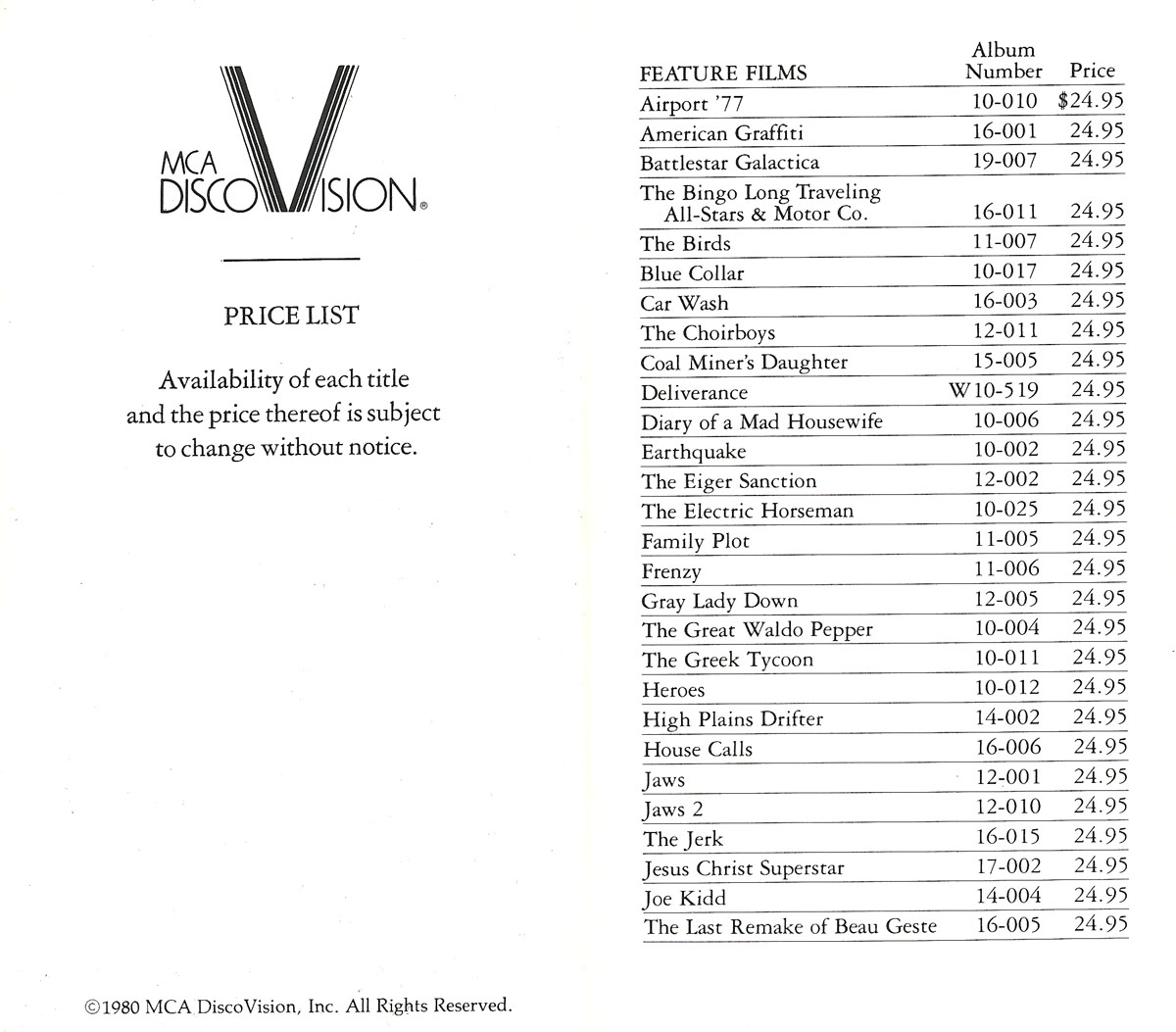

Fragments of the booklet with the first releases on DiscoVision. Full scans are available at laservideodisc.tripod.com .

Against this background, the first catalog of films on DiscoVision looks attractive - there are several dozen titles from 6 to 16 dollars. Interestingly, even the three-hour "Godfather" is quoted at $ 16. A typical VHS tape at that time at standard speed held only 2 hours, and this film was usually released on two cassettes.

But for some reason, there was no resounding victory. Even in the mid-nineties, at the height of the LD's popularity, the LaserDisc was only in 2% of American households.

Ahead of its time

LaserDisc didn't hit the market because it was ahead of its time. And this is also true.

The example above with "The Godfather" is just promises on release. According to the LaserDisc Database catalog , the film's release has been canceled. The Godfather came out on two LaserDiscs in 1981, but cost $ 35. The entire catalog is, as stated on the first page, only a promise to release this film on DiscoVision by early 1979. And MCA didn’t keep the promise.

Already in the catalog of May 1980 the prices of films are noticeably higher: full-length films cost 25-30 dollars.

The actual cost of films on LaserDisc was much higher than MCA expected. Movies usually cost $ 35-40, and special editions with bonus content (for example, a small documentary about the film and photographs) often came out for $ 100.

The first press releases about the MCA system reminded that there are 11 thousand films in the archives of the media giant. In the November 25, 1975 Hollywood Reporter, the head of DiscoVision talks about plans to release 500 films at launch. By April 1977, PR people reassured the impatient audience that there would be 300 films. This number decreased to 200, then to 113. Of these, only 81 actually came out, and some of them were released in such small batches and with such frequent defects that very few people succeeded trace the copies that have survived to us.

At the start of sales in Atlanta, the selection was limited to 50 films. In the following years, there were hardly 20 different films on DiscoVision in stores.

There was no stream of people wishing to get into the new media format: film studios were too slow to get used to the idea that films could be sold for private viewing. Why sell an arbitrarily reproducible copy when you can charge money for every view? In the pre-home video era, cinemas often played older films. By the way, something similar is happening in recent months, but due to the coronavirus pandemic and the lack of content caused by it.

There was a “chicken and egg” problem: if there are no films, there is no point in buying an expensive turntable; if the turntable is not bought enough, studios do not want to license films.

DiscoVision was truly ahead of its time. New market opening did not go as smoothly as MCA expected. New release catalogs have even begun to shrink. The actual production of the discs turned out to be much more expensive than the expected 40 cents: about $ 1.25 for each of the two sides of the disc.

A copy of the " frenzy " of DiscoVision. According to the owner, this disk even partially works.

Disc marriage was frequent. Of course, this was partly due to the novelty of the process: MCA was the first in the world to master the production of optical discs on an industrial scale. But the organization of production was also lame. There was a terrible story about the Carson Disc Replication Factory. The premises of the former furniture company were cleaned out as best they could, but it was impossible to get rid of the wood dust completely. They put plastic bags on the printing presses to somehow maintain the status of a clean room. The quality of the imported raw materials varied from batch to batch.

MCA executives did not expect such problems, as they got used to the analogy of a simple and cheap process of printing vinyl records.

The turntables were also unreliable. Early models with helium-neon lasers were very hot and often out of order. Philips lost money on each of the first Magnavoxes: they turned out to be more expensive to manufacture than expected, and the laser had to be assembled manually in the USA. Part of VH-8000 spent nine months of the first year on the shelf, awaiting repair.

The release of the Pioneer VP-1000 partially corrected the situation , although it experienced problems with CLV drives.

Much later, after the appearance of solid-state lasers in the eighties, the era of relatively reliable players with a full set of functions began. But even without the "childish" problems at the start, LaserDisc had no chance against magnetic tape.

Continued in the second part of the post.