Boeing Starliner post-flight service, photo NASA / Bill Ingalls

Twice almost lost

In NASA terminology, the mission was recognized as "almost lost with wide media coverage" ("high visibility close call"). The next term is the accident with the loss of the ship and possibly loss of life. The status is quite rare, and the last time it was designated the situation when in 2013 the astronaut Luca Parmitano almost drowned in a spacesuit on a spacewalk due to a clogged filter of the water cooling system.

The first bug showed itself 31 minutes after the start. The spacecraft did not perform the expected maneuver to switch to the flight path to the ISS from its original orbit. MCC tried to rectify the situation, but, as evil, these attempts were superimposed with communication problems, and as a result Starliner was in orbit unsuitable for rendezvous with the ISS, and with empty fuel tanks. Due to an error in the code, the spacecraft synchronized the flight time timer with the launch vehicle not at the start of the countdown, but 11 hours before launch. As a result, the on-board computer believed that the ship was at a different stage of flight than it was in reality.

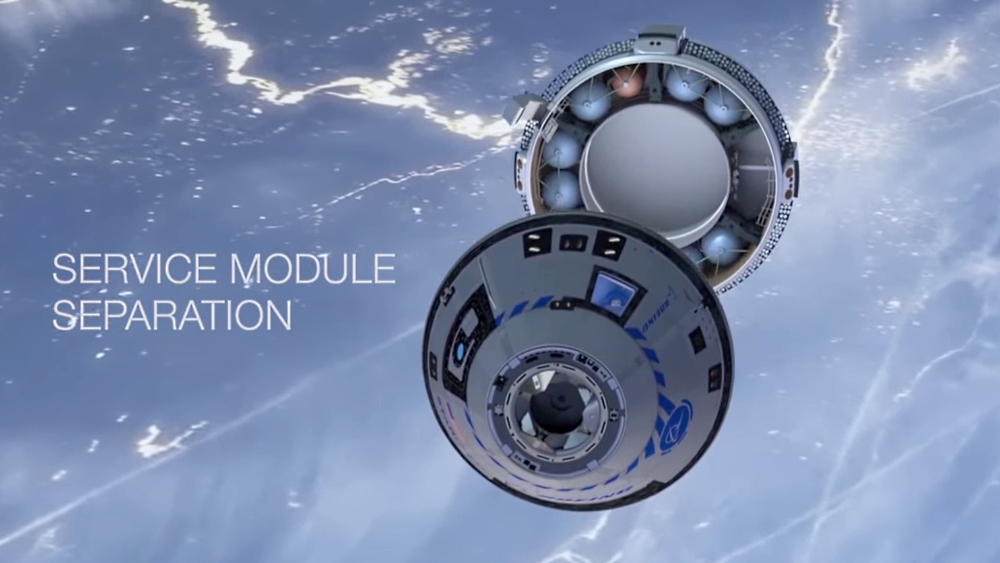

Separation of the compartments of the Staliner ship, a frame from the Boeing video

The second bug did not have time to prove itself. Because of the first problem, NASA and Boeing experts began to analyze the code to see if we missed anything else? And, as it turned out, not in vain. During landing, after performing a braking maneuver, the spacecraft had to split into a descent vehicle and a service module (shown in the illustration above, almost all spacecraft go through a similar procedure, for example, Soyuz is divided into three compartments, and Crew Draron drops the service module before braking). After separation, the service module had to perform a maneuver to escape from the ship, but due to an error in the code, the procedure was incorrectly transmitted to the controller controlling the process. As a result, the service module could hit the descent vehicle and cause trouble there.

The third problem was not so critical, but I drank a lot of the blood of the ground personnel. Throughout the mission, the ship had problems with communication with the ground, which made it difficult to control it from the MCC, and in the case of a manned flight, it would lead to difficulties in negotiations with the astronauts.

Two critical issues, each of which would have led to the loss of the ship if not for the intervention of the MCC, emerged during the design and development phase and managed to seep through numerous checks during the testing phase. Both problems were detectable through testing, and Boeing's processes could and should have found and fixed them.

What to do?

The full report contains proprietary and trade secret information, so NASA has published only a general overview, which is still quite interesting.

21 recommendations are directly related to testing. First of all, it is necessary to improve integration testing at both the hardware and software levels. On my own behalf, I note that errors that were not caught at the stage of integration testing still occupy a large share in the causes of space accidents. Further, prior to each flight, it is necessary to conduct a “dress rehearsal” with maximum involvement of the flight equipment, analyze its behavior and limitations, and take action on the detected gaps in the simulations.

10 recommendations were attributed to requirements, but in fact they also relate to testing. Requirements with multiple conditions should be better analyzed and decision coverage should be increased - the test coverage of conditions in the code. Let me remind you that 100% decision coverage means 100% statement coverage, but not vice versa.

35 recommendations should improve processes. And according to what it is proposed to improve, it is possible to reconstruct the discovered problems. Strengthening the code review and test data should fix the problem with the fact that errors in the code were not noticed either during the writing of the code (for the code review) or during the testing process (the test data was obviously insufficient). Greater involvement of experts in safety-critical areas should eliminate gaps in competence. And the proposal for changes in the documentation of the decision-making commissions should correct the situation when flaws in development and testing were not noticed or received too low priority for elimination.

The 7 recommendations are code fixes that will fix bugs taking into account the flight time and the procedure for separating the service module, as well as make the antenna selection algorithm more reliable.

And the last 7 recommendations relate to organizational structure and hardware. Changes await the organizational structure of safety messages (obviously, to better pass messages "we have an important problem here,"), external audit should be improved, and an additional filter will be introduced into the ship's design to protect against out-of-band interference.

Dear lesson

Despite the fact that there is nothing joyful in the story of the emergency flight, it will serve to improve the processes of creating space technology and flight safety. Of course, it is very annoying to miss in production bugs that could and should have been found during testing long before the flight. Now the first test flights should rather confirm the correctness of the decisions made, rather than detect unnoticed problems. The test flight was very instructive, but also very expensive. Boeing is now required to conduct another test launch at its own expense to ensure the ship is safe and flyable. Its exact date is still unknown, while November 2020 is planned.