Probably, the long-awaited moment, which I will talk about today, was in some sense inevitable. For years, there have been rumors that Apple will take advantage of its accumulated knowledge of ARM processor architecture and bring it to desktops and laptops. At the recent Worldwide Developers Conference virtual conference , the iPhone maker made such a statement... Of course, many were interested in the further actions of Intel - the rejected partner, the relationship with which led to Apple's decision on vertical integration. But I'm more curious to trace the fading of the platform that Intel defeated to win Apple's favor, as well as see the parallels gradually emerging between PowerPC and Intel. Today we will talk about a long list of processor manufacturers that Apple has lost interest in, using the example of the transition from PowerPC to Intel. If you disappoint Apple, you will not be too good.

It took Apple a couple of decades to get comfortable with this concept. (Internet Archive)

Information about the first project of Apple’s own processor surfaced about 35 years ago

In many ways, Apple has long been drawn to the benefits of vertical integration brought on by weaknesses in third-party processors. This company was, by its very nature, a vertical integrator.

But many do not know how long ago there was an interest in creating their own CPUs, and also that this was an internal initiative of the company. Last year, a document appeared in the Internet Archive from which one can understand the ambition of this project. Published in 1989 and published by an anonymous user allegedly associated with Apple, the Scorpius Architectural Specification explains the general concepts of multi-core processor architectures more than ten years before these technologies were widely used by PC users.

“Work began in the mid-80s and continued until the end of the decade,” writes the anonymous author who leaked this confidential document. “Today it is obvious to us that this project never saw the light of day. But it was attended by very smart techies, and from what I heard, the architecture was quite elaborate. "

Although the title is Scorpius on the cover, this project has long been known to Apple fans under a different name: Aquarius.

Here is his story: at a time when Steve Jobs was “expelled” from Apple, the company launched a research project to create a multi-core processor architecture. At the start of the project, this was a very theoretical area, and computer processors with multiple cores appeared in the PC only in the early 2000s.

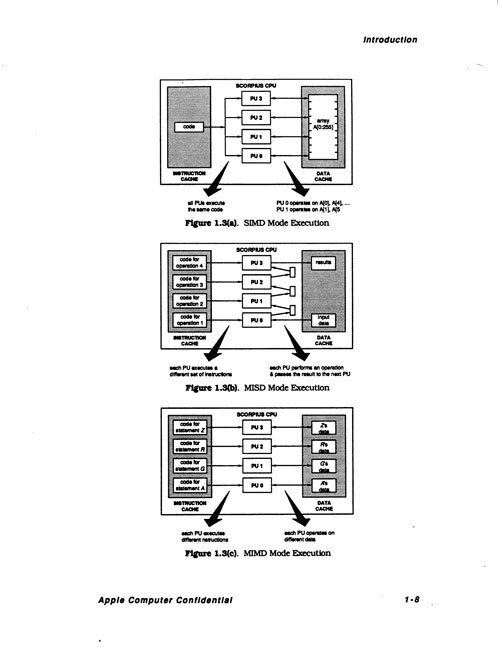

The illustration in the document explains the multi-core capabilities of the Aquarius / Scorpius processor. (Internet Archive)

As Low End Mac said in 2006 , Project Aquarius was an attempt by the company, then run by John Scully (in addition, leadership was heavily influenced by Macintosh Development Manager Jean-Louis Gasset) to return Macintosh to technical power, which weakened compared to new processors developed based on the RISC chip (reduced instruction set computer). RISC processors, one example of which is the ARM chipset , are aimed at speeding up the process by minimizing the number of instructions available.

Apple's proposed implementation was high-tech, initially enlisting the support of senior management, but essentially doomed from the start. It has become one of the many research “money black holes” that the company worked on in the late 1980s. The problem, according to Low End Mac author Tom Hornby, was this:

Apple - , , . , , , ( Fujitsu Hitachi). Intel Motorola . Apple , .

Even the launch of such a complex project cost millions of dollars spent on the purchase of the Cray supercomputer for $ 15 million approved by Gass, as well as on the salaries of dozens of employees. Vintage Mac software developer (and Gopher fan ) Cameron Keizer, who found the aforementioned document last winter , noticed that Chief Engineer Sam Holland, who started the project, had built something too high-level even for Apple itself.

“Holland’s complex specification was even more worrying for senior management, because its implementation required solving various technical problems that would have seemed difficult even to large and experienced chip design companies of that time,” he explains.

The project, which was developed before 1989, did not make it to implementation in silicon (which would still be financially overwhelming for Apple), but led to the creation of a detailed white paper explaining the potential of the Scorpius architecture - a unique chipset capable of performing many functions that are considered natural today. . In addition to several cores and parallel execution, Aquarius also introduced another key concept that is quite popular in modern processors: integrated graphics, which Intel did not integrate into its chips before the low-budget Intel i810 chipset , released in the 1990s.

The project was unsuccessful, of course, but in 2018 Gasse stated on his website Monday Note: later developments proved that the project was right in spirit:

Although the development work on a quad-core processor did not lead to immediate results, the Aquarius project served as an example of Apple's desire to control the future of its hardware. This craving again showed itself, but this time it was successful when Jobs bought Palo Alto Semiconductor to develop a series of Ax microprocessors that controlled iPhones and iPads; these microprocessors are widely recognized by the industry as the best in their category today.

Gassé is right, of course: the Aquarius has historically been the forerunner of Apple's current processor ambitions; but it also indirectly became one of the reasons for an important change in processors - the company moved from the Motorola 68000 series, which was then used in the Apple Macintosh, to the PowerPC, which was used on a large scale in the 1990s.

1990

This year, IBM released a hardware overview of its RISC System / 6000 processor, the first processor to use the POWER instruction set architecture. This instruction set became the basis of the PowerPC processor technology, which was jointly developed by Apple, IBM and Motorola in the AIM Alliance. This alliance was organized by the three companies to start developing a new generation of computer technologies in 1991 . IBM and others are even making processors based on this instruction set today, even though Apple dropped it 14 years ago. (This is not the only bet Apple made at that time on processors: the company also invested in ARM, which came in handy after several decades .)

Motorola PowerPC 750 300MHz processor, better known as PowerPC G3. Notably, Apple has sought to simplify the names of its PowerPC processors, resulting in the G3, G4 and G5 line. ( Wikimedia Commons )

In many ways, the PowerPC chipset introduced the consumer market to our world of 64-bit multi-core processors for the first time.

If you take a step back and think about PowerPC at a higher level, it is worth noting that, theoretically, he should have given Apple exactly the control over the fate of its processors that she craved.

On its own, Apple was not strong enough to build the kind of CPUs it hoped to build its computers on, so it teamed up with two companies with experience in chip making, putting all the hard work on them.

The PowerPC architecture turned out to be the most successful part of a partnership aimed at creating the future of computers in various forms, including hardware and software.

After the Mac was released in 1994, the PowerPC processor impressed Mac users as a very important upgrade from the 68000 line. Public TV technical journalist Stuart Chifet placed it at the beginning of an episode of Computer Chronicles :

PowerPC? «» Star Graphics -, . Quadra 950, 950 . 10 . 950 «» . 20 . ? PowerPC.

Even so, the success did not become true. IBM and Motorola joined Apple in its project to create a next-generation standard capable of advancing the technology industry ... but in the end, the only major company to use PowerPC chips in their computers is Apple. Yes, in the mid-1990s, you could buy an IBM computer based on PowerPC ( here's an example ), but her personal computer business, which she later sold to Lenovo, mainly used x86. 1995 InfoWorld

articlea problem was diagnosed that IBM faced in using the PowerPC architecture: "Building the necessary infrastructure requires scale to compete in price and support from third-party companies with Intel and Microsoft, and without such infrastructure, third-party companies are unlikely to support PowerPC," write the authors of Ed Scannell and Brooke Crothers. "However, IBM was very slow to build this infrastructure."

As a result, the PowerPC has never seriously competed with Intel on its own as a cross-platform CPU. (Nevertheless, it turned out to be much more successful in video games: during the seventh generation of console wars, all three main gaming platforms - Nintendo Wii, Xbox 360 and Playstation 3 used the POWER instruction set architecture in their processors, and a direct descendant of the original iMac processor was installed in Wii G3. Nintendo also used the PowerPC in the GameCube and Wii U.)

But over the years, Apple still actively took advantage of access to this architecture, which was so advanced that when the G4 processor was first released due to export restrictions on computing power, the government The US classified it as a weapon .

The four-chip IBM POWER4 module used in the servers. (image taken from IXBT Labs )

In 2001, a PowerPC-based chip managed to realize the multi-core technology that Apple had dreamed of implementing a few years earlier in Project Aquarius. The chip, the IBM POWER4 microprocessor, was the first commercially available multi-core microprocessor , and one of the first processors to cross the symbolic 1 gigahertz threshold for computing power.

Two years after the release of this server chip, a single-core version of it called the G5 appeared, installed in the Mac. It was the company's first 64-bit processor, while Intel x86 processors were only 32-bit chips. However, despite its power, difficulties with architecture and production led to the abandonment of its use by the company, thanks to the needs of which it appeared.

“PowerPC G5 changes all the rules. This 64-bit sports car became the heart of the new Power Mac G5, which became the fastest desktop computer. IBM has the most extensive experience in processor design and manufacturing, and this is just the beginning of a long and productive partnership. "

This is how Steve Jobs announced the PowerPC G5 processor in a June 2003 press release.that was used in the Power Mac G5, the company's first 64-bit computer. The “long and productive collaboration” actually ended two years later, on the same stage of the Worldwide Developers Conference, where Jobs showed the world the G5 chip.

Processor (and relationship) limitations that led to the end of Apple's long-term partnership with IBM and Motorola

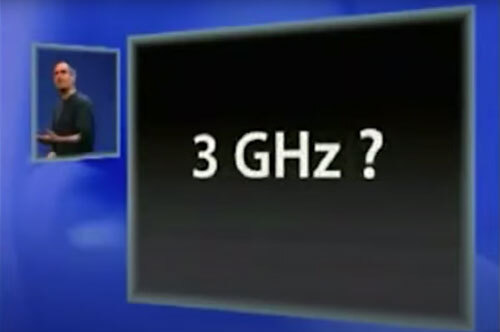

Over the course of two years, Apple CEO Steve Jobs has gone from delightedly claiming the huge benefits of the G5 processor over a regular WWDC audience to talking about the company's desire to completely abandon the entire PowerPC platform.

There were many reasons for this, but one of the most annoying was probably the 3 gigahertz problem. You see, when Apple announced the release of the Power Mac G5 in 2003, Jobs announced that the company would soon begin shipping a machine with a 3 GHz processor, which turned out to be a little more ambitious compared to the true capabilities of the G5.

Talking about upgrading the chip to 2.5 gigahertz at the 2004 WWDC, Jobs made the following repentant statement:

, , . ? : , G5 — , . PowerPC 130- . 130 90 , , . . 90 , , . - , .

Jobs was not happy to say that from the stage; perhaps this was partly due to what pointed to another drawback of switching to the G5: a problem with the Powerbook. As the Low End Mac explains , although IBM and Motorola have released mobile versions of different generations of PowerPC processors in the past, there have been some delays between desktop and mobile versions of PowerPC generations. For example, the PowerBook G4 only appeared in 2001, a year and a half after the release of the Power Mac G4. However, the architectural problems of the G5, preventing the processor from reaching 3 GHz, indicated that the processor, originally designed for powerful servers and workstations, could not be easily scaled down to meet the power-saving needs of a laptop.

There was a reason why the Powerbook G4 didn't turn into the Powerbook G5. ( mich1008 / Flickr )

Today, an Intel-style solution to this problem would look like this: develop a laptop with multiple cores to squeeze out more processing power from the previous generation. But multi-core CPUs were still new and their potential had not been tested, leaving the Mac laptop generation stuck in uncertainty. Ultimately, the Powerbook line reached its peak in 2005 with the release of the single-core G4 processor, which was four times faster than the original G4, released six years earlier.

As explained in an article on CNet 2009There have been many factors contributing to moving away from PowerPC, including access to Windows and withering partnerships with IBM. Another factor was the price - in this aspect, Apple could force IBM to make concessions. Unfortunately, she did not succeed.

"Apple paid a high price for IBM chips, which created Catch-22," wrote Brooke Crothers (curiously, this is the same person whose article we quoted in a completely different way above). "IBM had to hike up prices because it didn't have an Intel-class economy, but Apple didn't want to pay more, even though it was supposedly benefiting more from the more advanced RISC implemented in the PowerPC architecture."

For this and other reasons, two years after the announcement of the G5, Jobs entered the WWDC stage, acknowledged his technical limitations and announced his move to Intel.

“Looking ahead, Intel has the most solid prospects of all, ” Jobs said in announcing the transition . "It's been 10 years since the switch to PowerPC, and we think Intel technology will help us build the best personal computers for the next 10 years."

The Power Mac G5 at the end of 2005, one of Apple's latest PowerPC models before moving to Intel. ( Wikimedia Commons )

Despite this announcement, three G5-powered Mac models - the Power Mac G5, iMac and Xserve - continued to be sold. In late 2005, Apple even released a quad-core model - its first model with a multi-core processor (there were actually two). But it was felt that the Mac fans this whole situation a little upset. Longtime Mac writer John Syracuse summarized the situation in a 2005 article in Ars Technica as follows:

, , Mac . , Mac . ? , Quad « » Power Mac. PowerPC. , 3 . IBM . , Apple IBM .

This was partly a fallacy - now we all understand that multi-core processors usually have lower frequencies than their single-core counterparts, but at that time it was not obvious. Most of the disappointment, however, stemmed from Apple's failure to deliver on its ambitious promises to customers for understandable but sad reasons.

The internals of the Summit supercomputer, which used IBM POWER9 processors. ( Jason Richards / Oak Ridge National Laboratory / Flickr )

IBM has continued to refine its POWER processor line without Apple as the primary customer, with a new version of the POWER10 expected this year. The legacy left by the PowerPC line is still applicable in some niche areas, for example, today you can buy a completely new Amiga computer with a PowerPC chip based on the dual-core G5 architecture.

But the idea of PowerPC as a mainstream desktop computing platform essentially died with the completion of the partnership between Apple and IBM.

Modern Intel processorsmulticore versions of which Apple began to use immediately after their introduction, became a huge blessing for the gradual introduction of MacOS.

In the early days of the Apple-Intel partnership, their use was a kind of "pressure control valve" for the processor limitations that the Power Mac G5 created for the Apple processor line. They helped lift Apple laptops from the performance plateau, unable to take advantage of the 64-bit architecture promised to consumers by the PowerPC G5.

In many ways, moving away from PowerPC reflected a slow deterioration in the relationship between the three tech giants, which were destined to go in different directions. IBM was more comfortable using the POWER architecture in servers and embedded systems (ultimately the company made the architecture open source). Motorola completely pulled out of the chip business, handing it over to Freescale. And Apple is tired of waiting for new processors to match its release schedules and specifications.

Today, Apple is likely to feel a similar fatigue from Intel - a company that continues to produce wonderful chips, but with difficulty maintaining the same level of innovation; in addition, her small strategic mistakes turned into unexpectedly large failures. (As I wrote in StratecheryBen Thompson, Intel was keen to have its chip in the first iPhone, but decided not to drop the price. Bad move.) Its longtime adversary AMD is winning the battle for more cores at a lower cost. And Apple, it seems, is so tired of the Intel processor line that it completely abandoned entire product lines, for example, the Mac Mini and Mac Pro, which gradually faded.

However, like the PowerPC, Intel strives hard to meet the needs of its complex customer. The company's processors are good, but the speed and pace of their release does not suit Cupertino. And when the release of chips is postponed, Apple has to postpone the release of its products, that is, the cycle does not work perfectly, as was the case with the iPhone. Apple doesn't like companies that disappoint it - which is why Nvidia GPUshave not been installed in its computers for many years.

Of course, there are other choices in the x86 world - AMD's Ryzen and Threadripper lines may be tempting today, but Apple already has impressive mobile chipsets that can scale up much better than the G5 could scale down.

That is, apparently, Apple sees its own ARM chipsets as an opportunity for the long-awaited vertical integration, which the company has been moving towards for 35 years. It's good that this time she has enough money for that.