Image courtesy of the author. Based on a photograph by Patrick Thomas from Ansplash

Image courtesy of the author. Based on a photograph by Patrick Thomas from Ansplash

This is a translation of an article by David Clear on the Zettelkasten note-taking method, thanks to which the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann wrote over 70 books and 400 scientific articles. It is worth reading if you want to create your own knowledge base, organize ideas and stop forgetting important thoughts.

The article has been carefully transferred from the blog of the running editor . By the way, you can follow the announcements of new articles in my telegram channel . Subscribe not to miss anything!

Niklas Luman was an incredibly prolific researcher. Over 40 years of his work, he has published more than 70 books and 400 scientific articles covering a wide range of topics: sociology, biology, mathematics, cybernetics and computer science. On average, he wrote over seven books every four years of his career, plus an endless array of articles. And it wasn’t nonsense. The books became classics that made Luhmann one of the most important sociologists of the twentieth century ( pdf ).

Niklas's productivity is even more impressive when you think about how old tools he used. Before his death in a radio interview with Wolfgang HagenLuhmann said that he does not use a computer, only a pen, paper and a typewriter, on which he types clumsily with two fingers.

When asked how he was able to publish so much, Niklas would usually reply, “I don't make it all up myself. Most of the work happens in my Zettelkasten. I owe my productivity to this particular method. ” ( source in German ).

Because of such claims, Luhmann's Zettelkasten system acquired a mythical status and is so highly regarded that it has itself become the subject of a research project.. Luman never hid his method, and besides, it is quite simple. And that's great! We can take the approach of an incredibly productive sociologist and get the same advantages that made him so outstanding intellectually. Zettelkasten helped Luman:

- learn better

- better think

- publish more,

- be more creative.

So if you write non-fiction or work in the field of intellectual work, you are simply obliged to learn about the method of taking notes Zettelkasten.

What is Zettelkasten?

Luman describes Zettelkasten from several angles. Sometimes he called him a conversation partner or a second memory, the cybernetic system, chewing gum , and sometimes a sump .

Chewing gum? Sedimentation tank? What the hell is he talking about?

Let's start with the word "Zettelkasten". It came from the Pragerman language and consists of two roots: “Zettel” means a note or piece of paper, and “Kasten” is a box. The Zettelkasten is then just a box of notes, often called a filing cabinet.

Zettelkasten Luman was a piece of furniture. There are six shelving units, each with four wooden drawers filled to the brim with paper notes. This is what he looked like.

Image courtesy of the author. (CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Image courtesy of the author. (CC BY-SA 4.0 )

A bit disappointing, right?

Piece of furniture? So what made Luhmann so productive?

Not really. It's like giving a pencil to a Neanderthal, and he asks: “Is that all? This little stick allows you to remember things forever, communicate with each other through space and time? ”

As you will see, the Zettelkasten method is also associated with a piece of furniture, like a letter with a small stick. But before we analyze the method itself, let's list the shortcomings of other note-taking systems.

Why other note-taking systems don't live up to expectations

If you look like me, then you tried all the possible ways of taking notes:

- wrote in paper notebooks

- leave notes in the margins of books and printouts,

- used phones and apps

- ,

- - -,

- ,

- .

The problem with all these approaches is that they really do not help to find connections between ideas. On the contrary, they lock ideas so tightly that they are ultimately forgotten in a box under a bed, in a cloud, or in a folder somewhere on a computer.

Imagine you read a popular science book three years ago, a book on personal finance management a year ago, and now you are reading a blog article on how to be more productive. Each of these sources carries ideas that can be related. Moreover, six months ago, you could come up with a clever idea that was associated with all these ideas. But now you cannot see this connection between. Why? You may not have taken any notes. But if you did, then still something prevented you.

If you wrote down a note in a paper notebook, then recorded it in chronological order. Ideas stuck to the pages as if you had concreted them. If there is a connection between the idea at the end of page 17 and the idea at the top of page 89, then you probably won't see it. You will have the same problem with margins on a book or printout.

Usually digital notes are no better. Tools like Evernote quickly turn into landfill due to collector error- the tendency to collect a bunch of information without somehow processing it. If you keep notes in files and folders on your computer, you will soon forget about them, and documents will be covered with digital dust. And if you don't forget about your notes, they will still be organized in such a way that the devil himself will break his leg to build some kind of connections between them.

On the other hand, mind maps, concept plans, and tree-like lists come closest to the ideal solution. These tools help you find connections between ideas. The only problem is that they work well with several dozen ideas. You will not collect 90,000 ideas in one concept plan over 40 years and draw connections between them. But that's exactly what Luhmann did with Zettelkasten !

What Makes Luhmann's Approach Unique

If Luman wrote notes in a notebook, they would look something like this:

Image was provided by the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Image was provided by the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Notes would be walled up in an immutable structure, where they cannot be swapped.

If he kept them on cards or sheets of paper without any organization, they would look like this:

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 ) The

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 ) The

notes would float freely, but it would be impossible to track how they are related.

Luman could have done what folder lovers often did at that time, and kept notes on cards sorted into categories in different boxes or envelopes. The result would be something like this:

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

This creates an organization and looks neat.

The problem with this approach is that each folder creates a separate isolated storage, but ideas in the real world rarely fall into simple categories. For example, the idea of complexity is represented in biology, physics, mathematics, social studies, engineering, and who knows where else. So which folder should you put your note on the concept of difficulty in ?

Another problem with the folder-based approach is that it makes it difficult to create links between ideas that are put in different folders. Each note refers to others in the same folder, but it can also be linked to notes in other folders. For example, a note from Folder 1 may also contain ideas that relate to other notes from Folders 2 and 3. With a folder structure, you cannot save and trace these relationships.

You can try to implement an approach that uses tags instead of folders:

Image provided by the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Image provided by the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

This is a big step forward compared to folders, because now categories are not mutually exclusive. A post can have more than one tag, and you can see a whole collection of different perspectives at once, depending on which tag you're focusing on.

Tags are everywhere and many note-taking apps support them. But you do not need to use any fashion app. Luhmann knew about them and used Zettelkasten in his paper version.

Despite the benefits of tags, Luman wasn’t enough. He still saw too many limitations in them.

Anyone can confirm that if you file thousands of notes and tag them meticulously, then individual tags will not help much to see the links between notes. In reality, if there are thousands of notes per tag, the entire collection will be as confusing as if there was no organization system at all. Ultimately, each tag turns into a big messy dump.

Luhmann went one step further. Instead of relying only on tags, he also linked notes together. The result is the following system:

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Notes and ideas are not just linked, their links can be explicitly traced. This creates a network of ideas and gives huge benefits.

Think of it this way. The Internet or the worldwide computer network, to be more precise, is also a network of ideas. When you click on a link, for example this one , you are moved from this page (which you are reading right now) to the Wikipedia home page. From there, you can click on the next link and thus jump from one page to another while exploring the Web.

Now imagine that instead of combining knowledge on the Web, all sites are simply put into one folder without links. All Wikipedia pages, all blog posts, all stories on the Medium, all articles of various news publications, all YouTube videos, countless pages that form the Internet. They were all piled up inside one folder. You can never figure it out.

Now, imagine if someone suggested using tags to clean up this mess. Most likely, this idea will seem crazy to you. What? I need to organize an infinite number of sites in this folder using what? A million tags? This is contrary to common sense!

No, the solution to organize a huge amount of information and make it understandable is to use the network. This is why sites around the world are like neurons in your brain, organized into networks. And this is why you should connect all the interesting ideas that you want to keep track of throughout your life into a network of notes.

The main advantage of Zettelkasten

Using the Zettelkasten method, you turn notes into elements woven into a larger web of ideas. Instead of collapsing due to the addition of new elements to the system, on the contrary, it is getting better. Just like your brain. Nobody can say that more neurons make you dumber. Same thing with Zettelkasten. The more notes, the more ideas and connections, the smarter Zettelkasten becomes, and your publication gets additional depth.

Talking that Zettelkasten is getting smarter is not just a beautiful metaphor. Luman took it quite literally.

Let me explain.

Claude Shannon , the father of information theory, studied communication and the need to estimate the amount of information transmitted when two objects interact. The rating he found was calledproprietary information (also known as information volume or Shannon information). Shannon determined how much information is contained in the message depends on how surprising it is.

Wait what? More amazing, more informative? Exactly!

Imagine that you ask a duck a question and get a quack in return. Then you ask the duck another question and get the quack again. You ask again and again, and the stupid duck continues to quack. It quickly dawns on you that you are not communicating. Nothing out of the ordinary is happening. The duck does not transmit any information. She just quacks. This is not a conversation with a smart partner.

Now let's compare this with the already formed Zettelkasten, which contains thousands and thousands of ideas. You have a question with which you are immersed in Zettelkasten, moving from one idea to another through the links between notes. Since there are so many ideas here that you have collected over the past years, you probably forgot most of them long ago. Zettelkasten reveals itself through ideas that you added to it years ago and no longer remember. Thus, plunging deeper and deeper into the search for an answer to your question in Zettelkasten, you get answers in an unexpected form. The system is thus smarter than a duck, and it is because of this that Luhmann called him a conversation partner .

Of course, to take advantage of these benefits, Zettelkasten must mature to a certain level. At the very beginning, when it contains only a few notes, you will not be surprised at the results, as you added them recently. However, over time, Zettelkasten will grow from an apprentice to a full-fledged partner in writing. Until then, it will be a good storage for notes like a notepad or a fancy app. In fact, Zettelkasten is the most convenient note taking system, as it has several more advantages.

Study Aid

Reading does not magically increase your knowledge. If a text just caught your eye and entered your short-term memory, this does not mean that you learned something from it. If all you do is read, and you’re not doing it for fun, then you’re wasting time. Anything that enters your short-term memory is bound to be forgotten and useless in the long run. Years later, the effect will be the same as if you had not read this book or article.

So if you are reading to increase knowledge, take notes. And if you are going to take notes, then try Zettelkasten.

Zettelkasten will not only be a secure repository for the knowledge you collect over time, but will force you to create notes and write connections between them.Zettelkasten will improve your understanding of the material you are reading . This conclusion was reached by researchers Annie Piolat, Terry Olive and Ronald T. Kilog ( pdf ).

[Most] research confirms that non-linear note-taking strategies (such as tree view lists or matrices) improve learning outcomes more than linear writing of information, and that graphical and concept maps also educate skills in selecting and organizing information. As a consequence, non-linear strategies are best suited for memorizing information.

Did you notice the connection? Linear recording of information in a notebook is not a damn thing. Non-linear note-taking, graphic and concept maps decide! And what is Zettelkasten, if not one huge map of knowledge?

Additional focus

This is from personal experience. I have noticed that using Zettelkasten I concentrate much better on reading. I think this is because the method turns reading into a mission. I am not just reading, but doing the task of finding ideas, isolating them from the text and feeding my Zettelkasten in the form of notes. I have a crystal clear goal: to feed the Zettelkasten. I'm not just reading from an unclear intention to become smarter. A clear goal makes reading more fun, and I get into the stream faster .

Less frustration

The Zettelkasten method makes reading complex texts less disappointing. It is not necessary to understand the entire text. You are just looking for ideas that you can implement in your Zettelkasten. Who cares if you don't understand everything? As long as you collect ideas, you grow your knowledge base, and the text acquires an additional level of benefit.

Less waste of time

Researching with Zettelkasten is no longer a waste of time. You never have to worry about whether a piece of information deserves a room in Zettelkasten or not. If it's interesting, add it, even if you're not sure how much it relates to the current writing project.

Remember, Zettelkasten is designed to store knowledge for the rest of your life. If some pieces of information are not suitable now, they may come in handy in the future. You never waste time adding new ideas and connections. Zettelkasten gets better by collecting more ideas.

I think better

As Don Norman wrote in the book Things that make us smarter: Protecting human attributes in the age of machines : “The power of an unarmed brain is greatly overestimated. Without outside help, memory, thinking and reasoning work with limitations. [...] Real strength comes from invented external cognitive aids. "

Luman, using his Zettelkasten method, just created such an external helper. Zettelkasten not only helped his memory by acting as a means of collecting ideas, which he could then return to, but also improved his thought process. That is why he said that “Without notes [in Zettelkasten], with my own mind alone, I would never have gotten to such ideas. Of course, my head is used to write ideas, but all the laurels cannot go to her alone. ” ((original in German )

I think Zettelkasten's power to improve thinking is due to three main factors.

Firstly, using the Zettelkasten method forces you to write. According to the method, you must write notes in your own words in order to know for sure that you will understand them in the future. And as anyone who has ever written something knows, writing turns hazy thoughts into understandable ideas.

Second, by adding new ideas, the Zettelkasten method forces you to see which existing notes you can connect with. This broadens your thinking process, forcing you to think about how new ideas relate to those that you thought out before.

Thirdly, Zettelkasten can keep track of thoughts. The thread of reasoning is nothing but a sequence of ideas, and the Zettelkasten is the connection of many ideas. So you can think about something today, save the whole process in Zettelkasten as linked notes, and then, at any time in the future, continue to think in this direction, adding new thoughts and connecting them with the previous ones.

More productivity

Zettelkasten gives you a systematic way to explore information, build a knowledge structure and develop thinking. It provides a process by which you ultimately come up with new ideas. This has two advantages.

First, having a process that you can follow automates the way you handle a specific task, eliminating the need to think too much about the next step. This makes work more efficient and productive.

Secondly, the number of new ideas is one of the most important productivity metrics of any author who writes non-fiction. Approaching the process of creating new ideas systematically, Zettelkasten directly affects the objective result: the number of new ideas that you write about.

Growth of creativity

Zettelkasten is designed to find connections between any past ideas you have written down and any new or future ideas you still have written down. This makes Zettelkasten an incredible creativity tool. At its core, creativity is nothing more than a combination of ideas. All new ideas are based on the past. The piano plus a letter - a typewriter, a phone plus a printer - fax, the idea of a desktop with files and folders along with a television screen and a computer create a graphical user interface. Any new idea is a remix, and the main goal of Zettelkasten is just to remix ideas.

Zettelkasten principles

Zettelkasten is a phenomenal tool for storing and organizing knowledge, expanding memory, creating new connections between ideas, increasing the effectiveness of writing. However, to get the most out of Zettelkasten, you should learn a few key municipalities.

- The principle of atomicity. This term is introduced by Christian Titz . It means that each note should contain only one idea. This makes it possible to combine ideas with laser precision.

- The principle of autonomy. Each note should be self-contained, that is, be self-contained and understandable on its own. This allows you to move, recycle, split, and merge notes independently of their neighbors. It also ensures that notes remain useful even if the original source of information is lost.

- . , , . , . , « — , . , , Zettelkasten» ( ).

- , . , , , . , , , , .

- . ! , Zettelkasten, , , . Zettelkasten .

- . , , . .

- Zettelkasten. , Zettelkasten , , .

- - . , . , Zettelkasten « », « ». .

- . , . , .

- -. , -. , , .

- . . , , , . Zettelkasten , , . , , , .

- Add notes without fear. You will never have too much information at Zettelkasten. The worst thing that can happen is that you add a note that you can't use right away. But adding a note will never break your Zettelkasten or spoil its functionality . Remember, Luhmann had 90,000 notes in the Zettelkasten.

How to implement Zettelkasten

If you have read up to this point, then you don’t find a place for yourself to start your own Zettelkasten. If so, then I have good news. You can start right now. No need to buy expensive software or, God forbid, a large bulky set of wooden shelving, as in the original Zumtelkasten Luman .

Paper solution

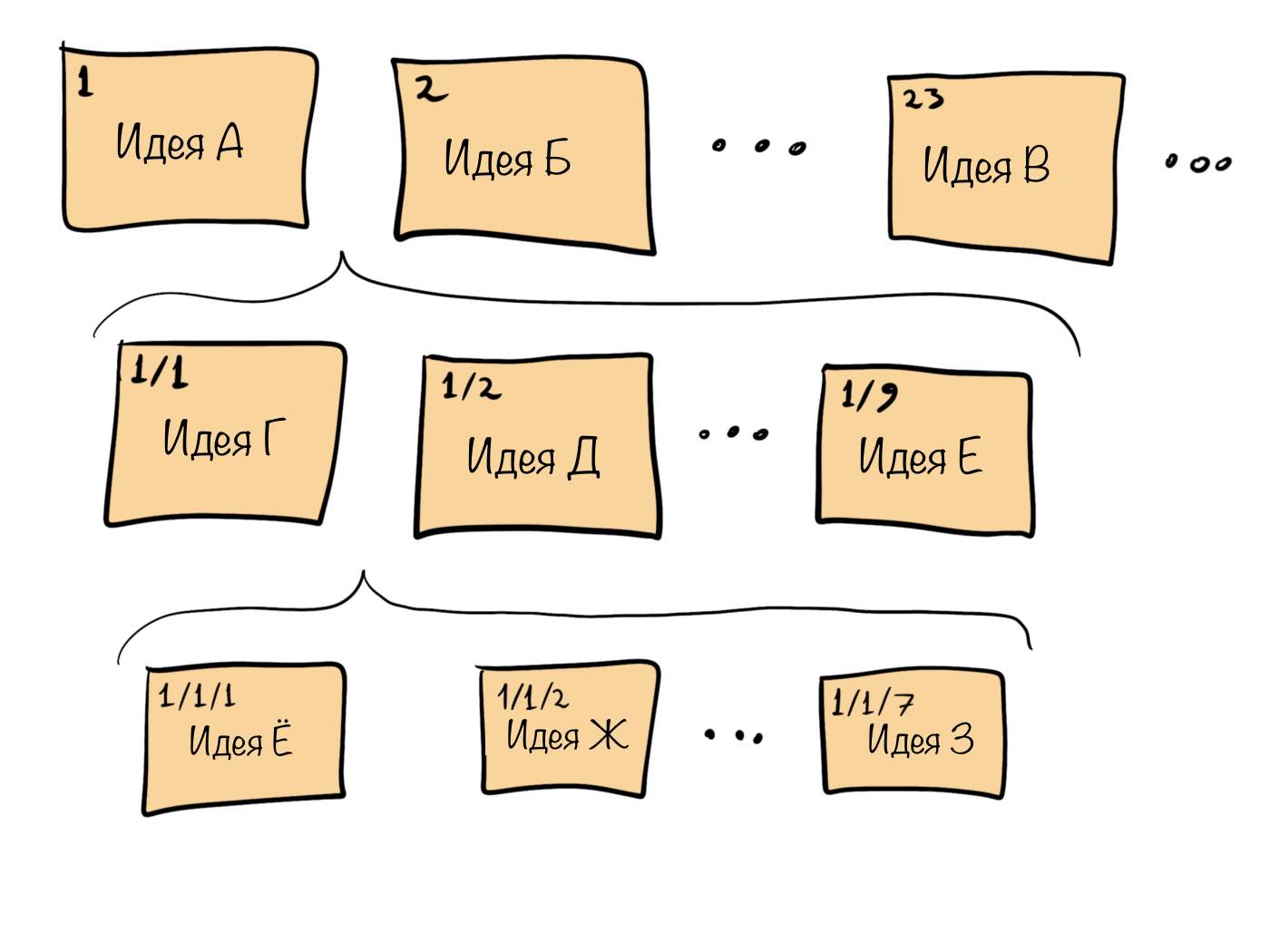

If you want to use only paper according to the precepts of the old school, then all you need is a shoebox or similar container and a set of cards or papers that you will cut to a suitable size. Then start reading or thinking, and each time you come across a new idea that you would like to keep, write it down on a separate card. Add a unique number in one corner of the card. Luhmann was very simple, he numbered the cards in order. If you want to use this approach, write on the first card that you created, number 1, on the second - number 2, and so on:

Image provided by the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Image provided by the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

If you later want to add multiple cards between numbers 1 and 2, just put them there with intermediate numbers 1/1, 1/2, 1/3, and so on:

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

By adding additional fraction characters, you can place new cards between previous ones. For example, to add cards between numbers 1/1 and 1/2, place 1/1/1, 1/1/2, 1/1/3, and so on on them.

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Now, to create a link between two cards, you need to use an ID. For example, if you want to create a connection from card 1/1 to card 1, simply write the number 1 somewhere on card 1/1. Also, if you want to create a link between card 23 and card 2, write 2 somewhere on card 23. Continuing this way, you can connect all the cards however you want.

Image courtesy of the author. (CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Image courtesy of the author. (CC BY-SA 4.0 )

If you want to add tags to cards, just write them along with a note:

Image provided by the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Image provided by the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

To make it easier to find cards with individual tags, create a note where you list them all, and after each tag, write down a list of notes that use it:

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Image courtesy of the author. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

That's it! This is a basic application of the Zettelkasten paper card method. Luhmann did exactly that, except that he used an alphanumeric system to identify his cards. Niklas found it easiest to use combinations of numbers and letters. If you're curious, check out his cards here. (It’s important to note that the notes on the cards are in German, exactly as he wrote them).

Digital solutions

If you want to go digital, you have several options. You can use applications such as Zettlr , Evernote , 1Vreiter , aye Vreiter , or any of their other analogues listed on Zettelkasten.de . You can also use personal wikis , plugins for text editors such as Wim or Sublime , or use a combination of analog and digital when you write notes on paper and then scan them .

Since Zettelkasten was conceived to be used throughout life, I would advise you to create a system that will have no future problems and is not tied to a specific manufacturer. Personally, I use plain text without formatting for this.

My Zettelkasten is a dropbox folder. This allows you to access Zettelkasten from your computer, phone or any browser. Each note is a separate text file that lies inside this folder. There are no subfolders. Everything is as horizontal as possible.

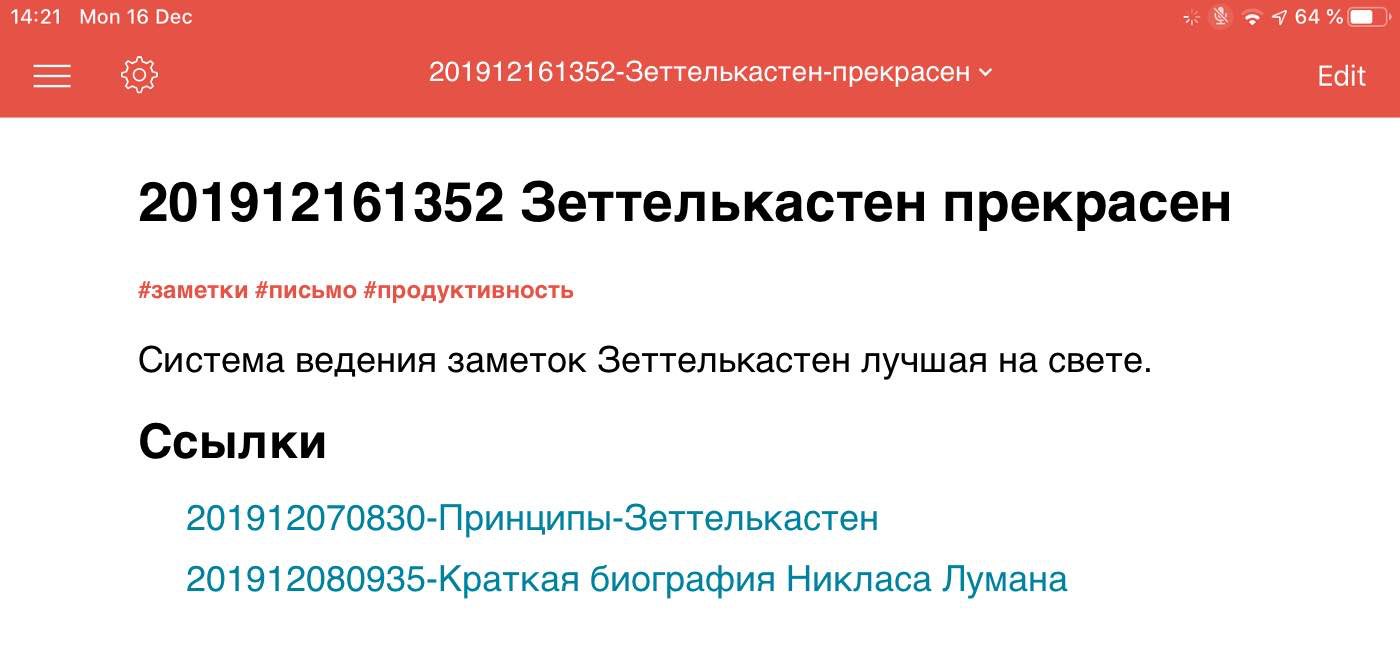

When I create a new note, a new text file is generated, the name of which represents the timestamp and title, as Christian advises from Zettelkasten.de... For example, right now is December 16, 2019, 13:52. So if I create a note titled “Zettelkasten is beautiful,” it becomes a new file called 201912161352-Zettelkasten-lovely.txt .

Then I write the content of the post using a combination of markdown and wiki-style links with double brackets. So the file 201912161352-Zettelkasten-wonderful.txt can contain the following information: The first line is the title of the note, the second is a list of three hashtags, the next is the idea that I wrote down and the last two: links to documents:

# 201912161352 Zettelkasten

# # #

Zettelkasten .

##

- [[201912070830--Zettelkasten]]

- [[201912080935- ]]

201912070830--Zettelkasten.txt

201912080935- .txt

Since this file is just plain text, it can be opened with any text editor on any computer, phone or tablet. This protects the system from any future problems and makes it independent from individual applications. But if you have a good text editor that supports markdown and wiki-style links with double brackets, then you see the note already formatted. For example, with 1Writer for iPad , it looks like this:

Screenshot taken by the author

Screenshot taken by the author

Clicks on the blue links open the required files. This makes navigating the Zettelkasten easy. However, I could use any other text editor that supports markdown and wiki-style links, or even doesn't. In the second case, I would have to select the text between the two brackets, press control + s to copy the name of the file that I want to open, and then press control + vi to paste the file name into whatever tool I am going to use to open next file.

Eventually

Zettelkasten Luman is different from other note-taking systems. Rather than being a helper for your next writing project, the method is designed to help you think, write, and publish throughout your life . It's built to collect as many notes as you want, without becoming an unusable mess. Its main purpose is to find dependencies between seemingly unrelated ideas.

Luhmann denied organizing notes in a purely linear fashion or according to given categories. Instead, he turned his knowledge base into a network of ideas that grew organically.

If you apply the method in your life, you will find many ideas glued together with books and notebooks, websites, newspapers and other sources. With the Zettelkasten method, your job is to free these ideas from the captivity of their sources and turn them into notes, collected in the main repository - your Zettelkasten - where they will be linked with other notes. Ultimately, you create a collection of ideas where there are no boundaries between their types, meanwhile they are old or new. Each idea is easily intertwined with others and gives rise to new ideas. This clearly separates the method from other note-taking systems based on notebooks, folders, or tags.

So if you are worried about remembering ideas that you bump into, if you care about how ideas relate to each other, if you want your own ideas to come to you, try the Zettelkasten method. He was created to manage ideas on a large scale and made Luman an amazingly prolific writer.